After 1866

Chronicles from occupied Venetia

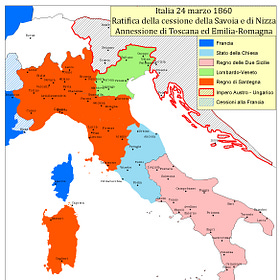

We have already covered the topic of the annexation of Venetia to the Kingdom of Italy in 1866 in a previous article, and in this article we want to expand on it, going more in-depth on specific cases and detailing how life went on for Venetians under the new regime.

Episodes such as these may seem inconsequential, but each manages to evoke how life was like in an often neglected period of Venetian history, whose primary sources were often censored or hidden by the new italian regime, and whose resonance in Venetian public consciousness is to this day hampered by the pro-unionist rhetoric that is endemic in italian historiography - which in turn informs the international perspective of academia as a whole on Venetian history.

This article will be structured as a compilation of short pieces originally written in Italian by Serenissima News. Links to each specific article are available by clicking on each contribution’s title.

October 1866, “Operation Plebiscite Fraud” also begins in Polesine

It has now been 159 years since the infamous plebiscite that condemned us to become part of the italian state. The more time passes, the more we realise that the vote (supposedly) cast by Venetians was not the true will of the people, but rather a fraud organised and managed down to the smallest detail.

The Italian occupation of Polesine began as early as July 1866.

The mere fact that the Italians had occupied the territory of the Venetian provinces militarily since July 1866 (their entry into Rovigo is dated July 10th) should lead us to believe that those votes were a sham.

If we accept the figurative representations of the time and the pro-Risorgimento texts from Polesine, they tell us of a triumphal entry of the “Liberators” (the umpteenth) into Rovigo between two wings of a jubilant crowd, to put it in Italian terms, “almost delirious”.

Unfortunately, official italian historiography never mentions that on the night before the Italians entered Rovigo, those who could (and we are talking about entire families) fled the city so as not to relive the events of the July 1809 uprisings.

In short, can we really believe that the population was jubilant at the arrival of the Italians? I would say no.

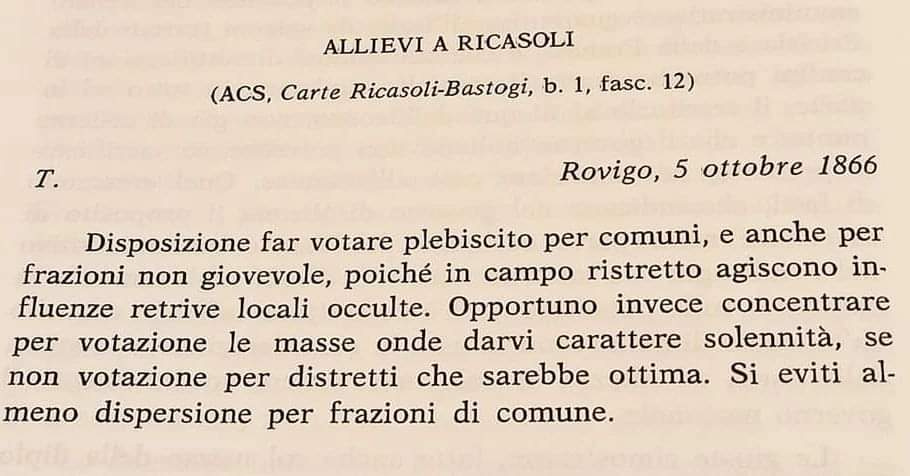

Was Polesine also witness to an intelligence operation to influence the vote?

It is clear from this other document that in Polesine too, the leaders of the Italian apparatus had in some way tried to influence the outcome of the vote in favour of Victor Emmanuel II in the weeks leading up to it. The photo below shows a telegram sent by the commissioner of Polesine Allievi to Prime Minister Ricasoli.

English translation:

“Holding a plebiscite vote for municipalities, and even for hamlets, is not beneficial, as hidden local influences tend to prevail in small areas. It would be more appropriate to concentrate the masses for voting in order to give it a solemn character, if not voting by district, which would be excellent. At the very least, dispersion by municipal hamlets should be avoided.”

It can be found in the book “Archivi dei regi commissari delle province del Veneto e di Mantova nel 1866” (Archives of the Royal Commissioners of the Provinces of Veneto and Mantua in 1866).

New evidence on the fraudulent plebiscite emerges from Polesine

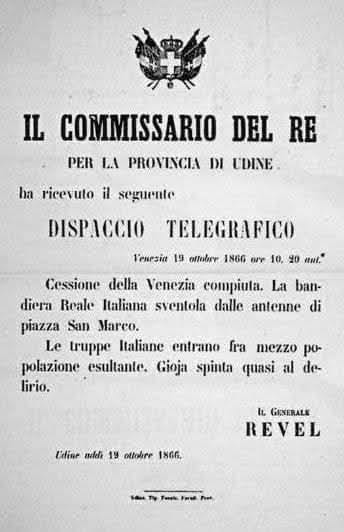

It is October 19th 1866 and Venetia is already under military occupation by Italian troops, despite the fact that the Venetian population still has to be consulted on whether or not they wish to become part of the Italian Kingdom through a plebiscite scheduled for October 21st and 22nd.

Theft in Venice...

The transfer of Venetia is complete. The Italian royal flag flies from the flagpoles in St Mark’s Square.

Italian troops enter amid jubilant crowds. Joy is intense, verging on delirium.

General Revel

Meanwhile, in Venice, at the Hotel Europa, the perfect crime is being committed. The Venetian lands are ceded to the Kingdom of Italy two days earlier than the scheduled vote, in total media silence.

...while in little Fasana, another example of the scam

At the same time, in a remote village in the Polesine countryside on the banks of the Adigetto, the Municipal Council of Fasana (my native village, now a hamlet of Adria) sent a short letter to its parish priest with precise instructions on how to best handle the vote according to plan.

A letter that gives pause for thought...

Fasana, October 19th 1866

To the Most Reverend Parish Priest of Fasana

On the 21st and 22nd, the plebiscite must take place in accordance with the Royal Decree. We therefore ask you to publish this from the altar for the common knowledge, given that the communists have set up two commissions, one in Fasana and the other in Bovina, gathered in the premises used by the schools, which will receive their ballots in their respective ballot boxes and will record the names of the voters.

The writer has no doubt that you will be able to add words of warm encouragement so that this may be spontaneous, solemn and dignified, worthy of Italy as a whole, and at the same time, the unity of our small municipality may rise majestically, singing the Te Deum.

The Deputation

This is what is reported in the document found by the undersigned in the Historical Archive of Adria in the Administrative Correspondence of the municipality of Fasana for the year 1866. Who knows what the Municipal Deputation meant between the lines to the parish priest.

At the time, Fasana was a municipality with no more than 1,300 inhabitants, while today it is a tiny hamlet of Adria with barely 400 inhabitants.

Now imagine if every municipality in Venetia, large or small, had sent such instructions to its parish priests in order to steer the outcome of the vote towards a resounding success with overwhelming percentages in favour of annexation to the Kingdom of Italy. Today, we would consider such votes to be those of a country under dictatorship.

The first fake news in Veneto? The results of the plebiscite on annexation to Italy (21–22 October 1866)

Veneto was annexed to Italy by a plebiscite held on October 21st and 22nd 1866, in accordance with the provisions of the peace treaty signed in Vienna between Italy and Austria on October 3rd 1866, according to which the annexation of Venetia to the Kingdom of Italy was “subject to the consent of the populations duly consulted”.

I will not dwell here on the fact that Veneto was actually transferred to the Kingdom of Italy two days before the vote, on October 19th, as stated in the “Official Gazette of the Kingdom of Italy” of the same day, and that therefore Venetians went to vote when everything had already been decided.

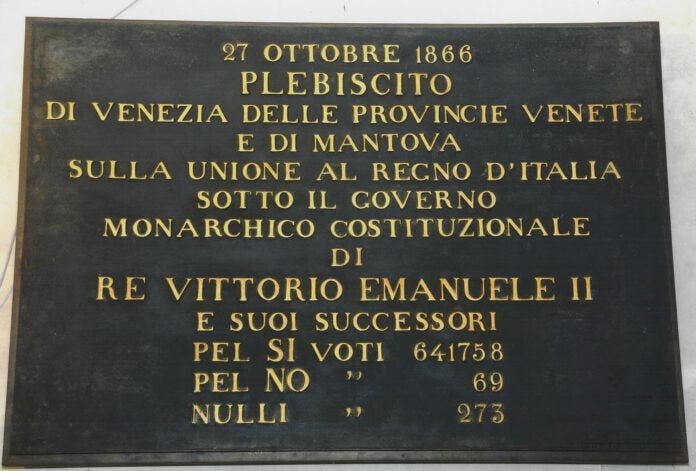

I will also not dwell on the way in which the voting took place, with different coloured ballot papers for yes and no, the obligation to declare one’s identity, and no secrecy of the vote. I would like to draw your attention to the various plaques that can be found in the squares and buildings of our region.

The plaque in the Doge’s Palace in Venice

I will start with the plaque displaying the overall results, which can be seen inside the Doge’s Palace in Venice. It states that there were 641,758 votes in favour, just 69 against and 273 invalid votes, meaning that 99.99% voted in favour.

Let’s move on to the plaque displayed in Palazzo Moroni, the seat of the Municipality of Padua, where we can read 15,280 “all in favour”. Well done, Padua!

The one displayed in the Palazzo dei Trecento in Treviso shows that there were 84,526 votes in favour, 2 against and 11 invalid votes. In Bassano del Grappa, another triumph: 3,508 in favour, zero against and 14 invalid votes.

Incredible results that regime historians do not dispute

So, I will leave aside all historical, cultural, economic and social considerations and focus solely on statistics: is it possible that out of almost 650,000 voters, there is a percentage of 99.99% of votes in favour?

Scholars categorically rule this out, because there is the so-called “mistake vote”, because there are always a few contrarians, etc. It is mathematically impossible for such a large number of voters to reach 99.99% of votes in one direction or the other... Yet regime historians are careful not to dispute such data.

Padua: not a single vote against. Is this credible?

And again, are the data appearing in Padua, Treviso and Bassano del Grappa credible? It is not credible that there was not a single vote against in Padua, it is not credible that the same thing happened in Bassano and that there were only two votes against in the entire province of Treviso.

And if the data is not credible, it is falsified; but these things must be said, because otherwise we become accomplices of the falsifiers; instead, there has been a code of silence surrounding the whole issue of the fraudulent plebiscite on the annexation of Venetia to Italy for over 150 years.

Don Carlo Mazzolini, the priest who ended up in prison in 1866 because he was an ‘enemy of the italian government’

Don Carlo Mazzolini was born on August 24th 1803 in the parish of Tolmezzo, in the province of Udine, and regularly attended all his studies at the bishop’s seminary in Udine.

After becoming a priest, he stood out for his somewhat “unusual” character and moved to the diocese of Concordia, where he served for several years as ecclesiastical administrator and parish priest of San Giorgio, one of the two parishes of Portogruaro (1834-1847). Bishop Fontanini entrusted him with Lenten preaching in various cities in Italy and Istria.

Don Mazzolini, parish priest of Ballò

From the diocese of Concordia, again because of his somewhat prickly character, Don Carlo moved to the diocese of Treviso. In 1847, he arrived in Ballò from Camalò, and in 1853 he was appointed parish priest of Ballò, a hamlet of Mirano.

After more than ten years in the hamlet of Mirano, he asked the ecclesiastical authorities to be transferred to another position. His request was granted by the Bishop of Vicenza, Giovanni Antonio Farina, “his former bishop who knew him well”. Here is what Monsignor Farina wrote to Emperor Franz Joseph:

Letter to Franz Joseph

“Your Sacred Majesty,

the parish priest of Balò, Diocese of Treviso, Province of Venice, Priest Carlo Mazzolini, a most loyal subject of Your Majesty and Your Imperial Government, who has published several highly accredited pamphlets in support of legitimacy and triumph of justice, is in constant danger of his life in that parish due to the machinations of troublemakers and the wicked who have already designated him several times to be their victim, and wishes that I, his former bishop, who knows him well, bring him before Your Majesty’s judgement, invoking for him a transfer to some place or monastic residence, or better still, a canonry in Treviso, where there are already vacancies.

As I consider him worthy, I have the duty to present him to His Majesty, submitting some printed documents and highly recommending him to our new government.

However, the bishop of Treviso, Monsignor Zinelli, was of a different opinion and Mazzolini remained in Ballò.

Arrested by the Italians

This brings us to July 14th 1866, a few weeks after the end of the so-called Third War of Independence: shortly thereafter, Venetia would become part of the Kingdom of Italy through a fraudulent plebiscite.

On that day, it was the Italian vanguard who arrested him and took him to the prisons of San Matteo in Padua. According to Claudio Zanlorenzi, public opinion in the country described him as a “spy for the Austrian government, a stirrer of civil discord, and the author of reprehensible actions against morality and public decency”.

The following night, “some unruly individuals went to the priest’s house, tampering with citrus fruits and plants and foreshadowing further violence against both the person and his property”.

“Enemy of the Italian government”

According to the Municipality of Mirano, “this obvious enemy of the Italian government” had made himself “hated and despised by his parishioners in his private and parish conduct”.

Don Mazzolini remained in prison until September 1867; once released, he expressed his intention to return to Ballò, but the police commissioner of Mirano managed to block his return and the priest was transferred to Gorizia, then part of the Habsburg Empire.

The return to Ballò and death

But Don Carlo wanted to return to Ballò: after inviting him to resign from his post (February 17th 1869), Bishop Zinelli allowed him to resume full possession of the parish in June of the same year, with the possibility of resigning ‘if he did not feel able to take on the burden’; Don Mazzolini returned to Ballò. The exact date is unknown, but his signature can be found in the parish registers, where he signed himself “archpriest”, and on 15 November 1870, he recorded a baptism.

Four days later, on 19 November 1870, Don Mazzolini died at the age of 67 from “cardiohepatitis”: a few weeks earlier, the Italian Bersaglieri had entered Rome, putting an end to the Pope’s temporal power.

The political writings of Don Carlo Mazzolini

Don Carlo Mazzolini is also the author of an interesting little book entitled Quale possa, quale debba essere il migliore destino politico dell’Italia (“What could and should be the best political destiny for Italy”), printed in Vicenza in 1861 by “Tipografia di Giuseppe Staider”.

The Jesuit magazine “La Civiltà Cattolica”, year thirteen, vol. II of the fifth series, printed in Rome in 1862, describes it as follows:

“Light in weight, but serious in subject matter, and highly commendable in its sense of righteousness, justice and religion, this work sees its distinguished author attempt to penetrate the future by predicting Italy’s political fate: and after demonstrating the impossibility of a single kingdom or unitary republic, he sees a confederated Italy emerging from the urn of destiny and assigns the conditions for this.

In essence, he agrees with all true political thinkers: those who, persuaded by the failed experiment of the Piedmontese unifiers, now believe that the only possible unity for Italy is federal unity.”

Unfortunately, Don Carlo Mazzolini was wrong, and we are still paying the dramatic consequences of the unspeakable way in which Italy was united.

As for the bibliography, I would like to mention Claudio Zanlorenzi’s article “Storie di preti del Distretto del miranese a fine Ottocento” (Stories of priests in the Mirano district at the end of the 19th century) in issue four of “L’ESDE”, an annual journal of local history of the Mirano and Venice areas, and an article by several authors (F. Stevanato, Q. Bortolato and G. Marcuglia) dedicated to Don Carlo Mazzolini in issue six.

Rovigo 1867 – Freedom at bayonet point

Eugenio Piva: patriot and historical conscience of Rovigo

Eugenio Piva was born in Rovigo on November 1st 1820 into a family with deep ties to the Polesine area. Brother of the patriot Domenico, he was himself a staunch supporter of the Risorgimento, but not a blind one.

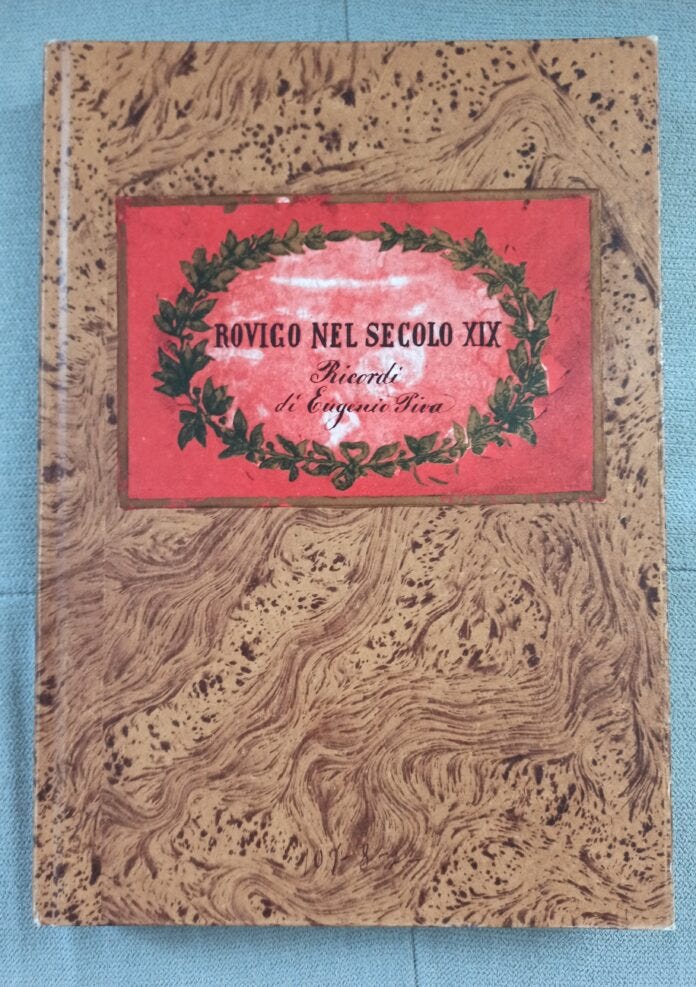

Employed by the Civil Engineering Department, he spent his entire life dealing with the hydraulic issues of the Polesine rivers, but he also cultivated a passion for historical memory, art and architecture, leaving behind a manuscript collection of exceptional value: Rovigo nel secolo XIX. Ricordi di Eugenio Piva (Rovigo in the 19th century. Memories of Eugenio Piva), with 35 handwritten papers and 19 pen drawings. Donated to the Accademia dei Concordi in 1892, this work is not only a chronicle of the city, but also an intimate and sincere reflection on what the city was becoming after the annexation to Italy.

Piva does not have the harshness of a polemicist, but the disenchanted lucidity of a witness. Although he believed in the dream of the Risorgimento, he was able to denounce what he saw happening to his people.

July 10th 1867: the celebration that turned into a riot

It is evening in Rovigo. The anniversary of the arrival of Italian troops in the city should be celebrated with shows and festivities. But something is wrong. The day before, some citizens were arrested for arguing with the municipal band. The population knows this and is not happy. They gather spontaneously in the square, demanding the release of those arrested.

And here comes the state’s response: the square is surrounded by troops, the crowd charged with fixed bayonets. In a few minutes, the celebration turns into repression. Twenty people were arrested. Rovigo seemed to be in “full revolution”, wrote Eugenio Piva. But who was the enemy really? There were no guns among the demonstrators, only voices and anger. Yet it was treated as a subversive movement. The people, the real people, understood at that moment that the new Italy was not a mother, but a mistress. And that evening, “liberation” finally revealed its armed face.

They were not liberators: the Savoy state and the betrayal of trust

That evening in Rovigo was much more than a local episode. It was the symbol of a fracture: the Kingdom of Italy, which had just taken hold in Venetia after the annexation of 1866, presented itself to the population with the face of bureaucracy and military force. The hope for a new, fair and open Italy was soon shattered by the reality of a centralised, fiscal and oppressive regime.

Citizens found themselves having to deal with quadrupled taxes, new regulations, paralysing bureaucracy and an unprecedented number of carabinieri and agents. The presence of the state was everywhere - except in the hearts of the people.

Eugenio Piva, as a technician and reporter, noted these changes with bitterness, and the press did not remain indifferent. Disenchantment was spreading everywhere, and even those who had enthusiastically welcomed unity began to regret it. The promise was freedom. The reality was control.

The voice of “L’Arena”: ‘Three times as many carabinieri’

One of the most striking testimonies comes from Verona itself. On January 9th 1868 - just fifteen months after the arrival of Italy - the daily newspaper L’Arena wrote:

“Among the thousand reasons why we abhorred the Austrian regime, we were greatly annoyed by the complexity and profusion of laws and regulations, the excessive number of employees, and especially guards and gendarmes, policemen and spies."

Who among us would ever have expected that the Italian government would have three times as many regulations, three times as many public security personnel, carabinieri, etc.?”

These are not the words of nostalgics or reactionaries, but of citizens who had believed in the dream of the Risorgimento. The italian state had proved to be more present, more demanding, more oppressive than the Austrian one. Those words, now forgotten, are a slap in the face to celebratory rhetoric and give voice to a popular sentiment that school textbooks have removed: not everyone welcomed the tricolour with enthusiasm.

Conclusion - A forgotten people, an Italy imposed by force

July 10th 1867 is not just a date. It is a wound. It is the moment when part of the Venetian people realised that the long-awaited Italy was not the one they had dreamed of in their salons or at their rallies. It was a harsh, fiscal, military reality. And that reality was recounted by one of them, Eugenio Piva, with honesty and pain.

Six months later, in January 1868, discontent exploded everywhere: in Polesine, in the Verona area and in many parts of northern Italy, the people rose up against the tax on milled grain, a tangible symbol of an Italy that did not listen but imposed, that did not liberate but collected.

It was a fiscal siege, and Venetia was among its first victims. For many, unification was not a conquest but a replacement of masters. And in too many squares, such as in Rovigo, bayonets took the place of dialogue. It was not a question of freedom, but of occupation in tricolour uniform.

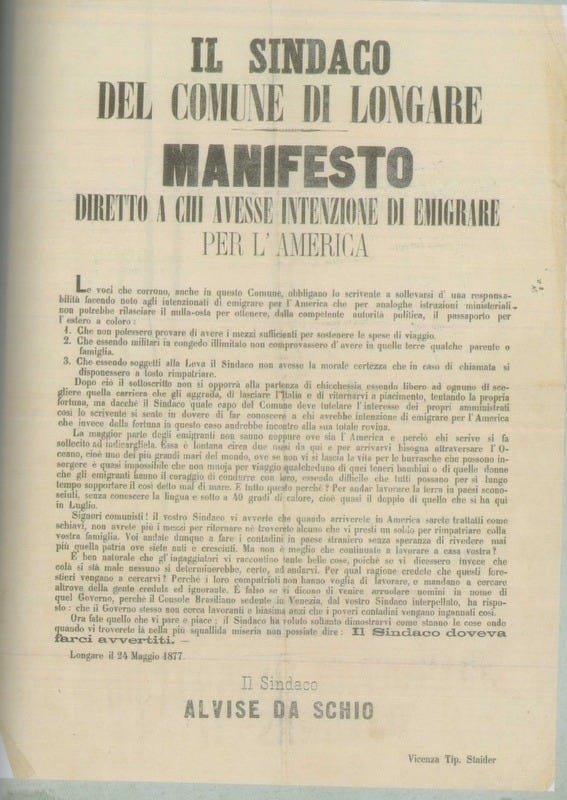

1877, poster by the mayor of Longare (VI): “Aimed at those who intend to emigrate to America”

On May 24th 1877, Count Alvise Da Schio, mayor of the municipality of Longare, had a poster printed: “Addressed to those intending to emigrate to America”.

The mayor, using direct and frank language, having learned that there were several “people intending to emigrate to America”, pointed out to his fellow citizens that passports could be issued to those who could prove they were able to cover the cost of the journey, to those who had unlimited leave and could prove they had relatives in those lands, and to those who, “being subject to conscription, the Mayor was morally certain that, in the event of being called up, would be prepared to return home immediately”.

“Emigrants, you are heading for ruin”

In addition to this, the Mayor:

“feels obliged to inform those who intend to emigrate to America that, instead of fortune, in this case they would meet with total ruin”.

And again:

“Most emigrants do not even know where America is, and so the writer is eager to point it out to them. It is about two months away from here, and to get there you have to cross the ocean... it is almost impossible that someone will not die on the journey... And all this for what? To go and work the land in unknown countries, without knowing the language and in 40-degree heat”.

“In America, you will be treated like slaves”

“Your Mayor warns you that when you arrive in America, you will be treated like slaves, you will no longer have the means to return, nor will you find anyone to lend you money to repatriate with your family.”

And so the appeal-manifesto concluded:

“Now do as you please: the Mayor only wanted to show you how things stand so that when you find yourselves in the most squalid poverty, you cannot say: THE MAYOR SHOULD HAVE WARNED US.’ (the bold capital letters are in the original manifesto).”

Venetia in misery after annexation to Italy

After the annexation of Venetia to Italy on 21-22 October 1866 through a fraudulent plebiscite, our land found itself in a situation of hunger, misery and despair unlike anything ever seen before in our history: Venetians had no choice but to emigrate.

Venetian Emigration - Part I

Between 1876 and 1920, hundreds of thousands of people from the Veneto region (nowadays including Friuli) left their homeland in the hope of finding a better life across the Atlantic, perhaps unconsciously carried along by the old dream of a Cucagna.

Entire villages left in search of fortune in America, duped by swindlers who recruited our people by promising to take them to a land of plenty, where they could harvest two or three crops a year.

The reality, however, was dramatically different: they were called upon to replace slaves (in those years, a law had been passed in Brazil abolishing slavery) and when they arrived, they found a situation even more tragic than the one they had left behind. Only after unspeakable sacrifices did they manage to build the minimum conditions for existence.