We will talk about Venetian Martiality, which is defined as a compendium of disciplines, techniques and equipment utilised in Venetia throughout the ages. The discussion will be conducted with the assistance of two experts on the subject, who are actively involved in the field of sports initiatives, re-enactment events and conference, festival and celebratory participation, both within Venetian lands and internationally, with the objective of preserving and transmitting traditions: Danilo "Łeo" Lazzarini and Marco Antonio Soldati.

Danilo “Łeo” Lazzarini

Master of Arms and historical consultant, with significant experience in the field of historical re-enactments and film productions. He has collaborated on major projects such as the remake of the film Ben Hur (2016), where he devised the march of the Roman soldiers, and the soon-to-be-released docufilm on the First Veneti.

‘To be able, even dimly, to glimpse for a moment what happened in distant times is something wonderful.’

Marco Antonio Soldati

Historical fencer and knife fighting instructor, trained at the Danilo Lajolo school. A martial artist with years of experience, but always committed to constant further training, deepening techniques and traditions related to historical martial arts.

We are going to take a bird's-eye view, just to stay in the cinematic theme, of what is the martial arts of the Venetian people, conversing freely about it. Let us start with what in the common imagination is perhaps the most representative, namely Renaissance fencing.

Were there fencing schools within the Venetian Republic?

MAS: To answer this question, it is first necessary to set some stakes and define what we are talking about. Historical fencing refers to the interpretation of fencing manuals written by fencing masters of all epochs prior to our own. Today we have manuals written roughly from the 13th century onwards, so historical fencing deals with that period: it is what has come down to us. What happens in earlier eras, on the other hand, is the prerogative of historical reconstruction, and consequently re-enactment, because manuals are lacking. If one day we were to find a manual, for example, on how to fight with the gladius, then it would be the subject of historical fencing.

ŁEO: For the Ancient Era there would be Flavius Vegetius Renatus, an author from the late Roman Empire, but it is more like a war manual than later fencing treatises. In his work, however, combat with the gladius is mentioned.

An art is spoken of when its memory has been lost...

MAS: Often such manuals, from the late medieval or modern period, originated as a result of patronage by some feudal lord. The various masters who authored such works clashed with one another, even making explicit references in their treatises to discredit or homage. Modern fencing was born from the evolution of historical fencing, interpreting its techniques and adapting them to a new context. So even the fencing that is practised today at the Olympics will one day be considered historical fencing because it is constantly evolving. A field that is always open.

A further difference between modern and historical fencing is that the former is internationally standardised today, while the latter has its own regionality which distinguishes it.

So returning to the question, if by ‘schools of fencing’ we mean facilities where the art was learnt, we have plenty of them in the Venetian Republic. If, on the other hand, we mean a stylistic vein that spans several masters, and perhaps extends to several cities, then this does not exist in Venice. There are, however, schools of fencing in Italy, such as Bolognese fencing and Neapolitan fencing. They have progenitors, founders of a certain style, who wrote manuals that were then handed down by their students, who in turn became masters and refer to them when teaching. On the European scene, however, the most structured is perhaps German fencing.

What are we going to study from these manuals? A fencing manual was a kind of university textbook: advanced tactical manuals aimed at people who already knew how to fight. The school therefore determined a thought, a philosophy related to the approach to combat. However, in the Veneto there existed and have existed many fencing masters and champions -let alone the athletes we see at the Olympics- who also wrote treatises, but no schools of thought on how to fence based on these treatises were structured.

It is therefore safe to assume that a young Venetian aristocrat of the Renaissance would have relied on a master to train in arms, would have learnt the techniques from the manuals of the Bolognese school, since it was one of the oldest and geographically closest, and if in the course of his life he had become particularly good at it once he had established himself as a fencing master, he could have written a book with his own input, thus departing from the philosophy of fencing on which he himself was trained.

Venetian masters of arms who wrote treatises include:

Vincentio Saviolo (ca. 1550 - 1590), born in Padua, is known to have written an English-language fencing manual, His Practise, published in London in 1595. He taught in England, significantly influencing British fencing at the time.

Nicołeto Ziganti (17th century), born in Venice, published the treatise Scola, overo, Teatro in 1606, which describes fencing techniques with the sword alone and with sword and dagger. His work contributed to the spread of Venetian fencing in Europe.

Bondì de Mazo (17th century), a Venetian master-at-arms, is the author of the treatise La Spada Maestra, published in 1696. His work represents an important milestone in the development of Venetian fencing.

Francesco Alfieri (c. 1610 - after 1690), born in Padua, was a master of arms and author of several treatises, including La Scherma (1640) and L'arte di ben maneggiare la spada (1653). His works offer a comprehensive view of the fencing techniques of the time and emphasise the refinement and effectiveness of the Italian style.

Giovanni dall'Agocchie (c. 1533 - after 1572), originally from Bologna, published the treatise Dell'Arte di Scrimia in 1572. It is considered one of the fundamental texts of Italian Renaissance fencing, with insights into etiquette and duelling strategy. Although originally from Bologna, his work influenced the Veneto area.

Fiore de' Liberi (c. 1350 - after 1409), originally from Friuli, is universally recognised as one of the greatest masters of arms in European history. His treatise, the Fior di Battaglia (Flos Duellatorum), completed in 1409, is the oldest surviving Italian fencing manual and an invaluable source for the study of medieval martial techniques. Its work includes detailed instructions on fighting with bare hands, long sword, dagger and other weapons.

Codex 33, a German fencing manuscript from the 15th century but possibly inspired by an older Italian treatise.

The rise of historical Bolognese fencing, however, occurred in the 16th century. Later the Spanish, French and Neapolitan schools emerged.

Does this proliferation of schools lead to a diversification or homogenisation of the various fighting styles?

MAS: This leads to an increasing uniformity of styles in the search for effectiveness. We go from the side sword, two-handed sword, etc. of the 16th century, for use in battle, to the duelling sword such as the strip of the 17th century, also helped by the emergence of firearms. Hence, sword and foil, civilised weapons that do not need to strike armour or engage in melee in battle. Hence, swords lose their edge and become long skewers capable of striking the opponent point-blank. In the 16th century we have treatises on weapons at auction. Giants for example is only strip.

So there are also treatises for weapons other than ‘swords’ in the strict sense? For example spears, daggers...?

MAS: Certainly. Dagger pole arms and shield arms and cloak, brocchiere, or broccoliero as you like. Fiore de' Liberi also contemplates the throwing of the sword pommel, a very “battle” move in case the sword breaks. Here, the formations and variety of weapons slowly give way to ultra-specialisation in the single sword, ever lighter, for civil combat.

ŁEO: If you think that firearms made armour useless, it is a natural evolution.

I open a small digression on this: in the arms race for World War I, the Kingdom of Italy was in the process of building new battleships with 280mm thick steel to withstand the blows of naval canons. In the meantime, the latter had evolved so much that it was impossible to build a ship with armour thick enough to withstand their blows: it was decided to redesign such a battleship by making it thinner, hence lighter, to facilitate manoeuvrability. This is exactly what happened to armour in the course of time, with a curious exception at the outbreak of the First World War with Farina armour, which later proved useless. They then switched to camouflage, and the Italian grey-green proved to be among the most effective. A paradigm shift due to the change in the use of weapons.

All this is interesting because it makes us understand how in the context of the Italian peninsula and the Po Valley there was always scope for innovation in the art of warfare, even though there was often a lack of systematically narrating it with treatises etc.

MAS: In fact, the rivalry between masters certainly had an influence: in order not to give credit to ‘colleagues’, many even recommended manuals written in other areas of Europe, consequently the latter became widespread.

ŁEO: Italian suits of armour were for centuries considered the best in the world, particularly those produced in Milan, renowned for their craftsmanship and strength. Form and substance. There has always been an important tradition of manufacturing arms and armour, including firearms. For one thing, the invention of the pistol probably took place in Pistoia. Another interesting fact is that Italian armour was stamped, as it was tested by firing a pistol shot, which was then covered by the shoulder strap.

MAS: The production of Italian arms and armour is also characterised by its ‘regionality’. A significant example is the Missaglia family, originally from Ello in Brianza, who moved to Milan. This family, whose real surname was Negroni, adopted the name ‘Missaglia’ from their home town. Among the most illustrious members were Tommaso Missaglia and his brother Antonio, known for producing armour of exceptional quality for European nobles and sovereigns. Their works were appreciated for their elegance and innovation in design.

Italian suits of armour, particularly those from Milan, were characterised by smooth surfaces and elegant lines, conducive to mobility and meeting the demands of top-level combat. This style also reflected Renaissance aesthetics, with a preference for agility and precision. In contrast, German armour, often associated with the Gothic style, had more articulated surfaces, with pronounced ribs and edges that increased rigidity and offered better protection against blunt blows, such as those from clubs or war hammers.

These distinctions were not purely aesthetic, but reflected the different martial traditions and battlefield needs of the respective regions. As the Latin adage, Ars longa, vita brevis, suggests, the artistic and technical excellence of Italian weapons has left a lasting imprint on history.

What about the Venetians? What innovations did they introduce in the context of warfare?

MAS: Venice favoured the brigantine: metal strips riveted inside a leather jacket, easy to produce and maintain.

This armour created the erroneous belief that leather armour existed, which is very common in fantasy video games today. In reality, they were steel armour covered in leather to be more comfortable to wear. As typical helmets, we have the bearded ones, with or without a concealment.

In the Renaissance, the Venetians were the only ones to systematically use the roncon (guisarme). There were also divisions of heavy infantry armed with mazzapicchio (mace), to loosen armour like a can opener. From the late 16th century onwards, the schiavone, with the characteristic gabio (guard), were developed and are perhaps the most characteristic in the collective imagination.

Each people had their own favourite weapon: the Germans favoured spits, the English the scythe, the Scots the guisarme.

LEO: Tactics include the invention of landing troops, first used in 1699 by Alessandro Morosini in the Morean War. The first bombs with toxic gas date back to the 15th century, an invention of the Venetian Arsenal. Then there are the galleys, the first sailing ships with side cannons, first used at Lepanto. Then there were constant optimisation studies, for example on gunpowder consumption.

MAS: Let us specify that landing troops per se, understood as divisions of soldiers housed on deck ready for action once they had disembarked, had been in use since the Ancient Ages. What the Venetians brought was naval support for them by bombardment from ships.

ŁEO: Curious isn't it? It seems so obvious to us today... Another ship-related tactic was the antennae: landing bridges to assault walls directly from the ship, taking advantage of the ship's height. This enabled the capture of Constantinople in the Fourth Crusade. Not to mention the deep-sea port: the creation of a true platform by lining up ships in special formations that created a walkable space. A fortress in the middle of the sea, to defend oneself in case of encirclement or to defend a position.

This is incredible!

ŁEO: You don't rule the seas for centuries without constant innovation, my friend! We also have depictions of sharpshooters specialising in launching ‘Greek fire’ with particular rifles. Basically, flaming bullets.

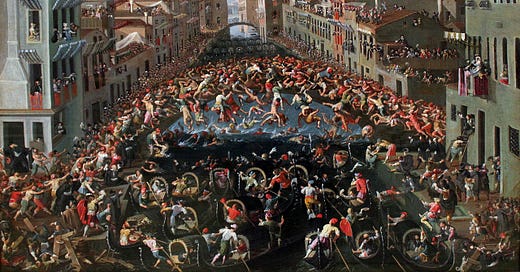

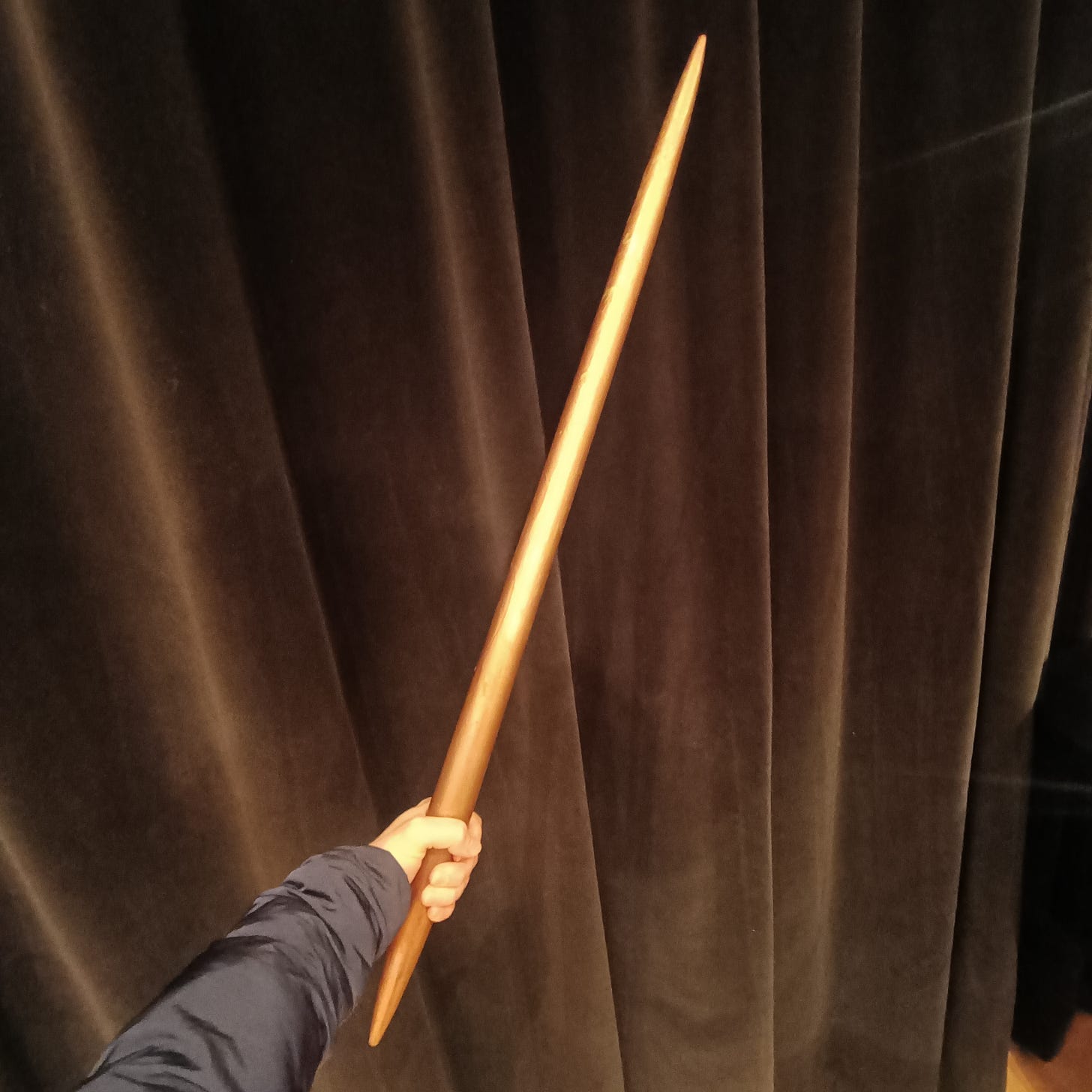

As for fighting styles, however, typically Venetian is stick fighting. In the Guerra dei Pugni [urban fights that took place between rival factions in the city of Venice, tolerated by the authorities, ed] a particular type of stick called cornolèr was used.

Made of cornel, a wood sacred to Mars: tapered and pointed on one side and with a strong handle on the other, about 1 metre long. Boiled in linseed oil to dehydrate it and make it very hard, a stick that could compete with swords.

It had its own developed fencing, identical to the ‘blade’ fencing but following the philosophy of the ‘trammel’: the loading of blows with movements of the wrist, since it did not have a wire and needed to accumulate energy for the blow by spinning. He also had a second fighting style, used instead in melee fights on the narrow calli and bridges of Venice, based on vertical blows and lunges. This was for fighting side by side between comrades-in-arms, in formation. This fighting in close formation, with these kinds of blows and a wooden weapon, is very reminiscent of the training of Roman legionaries. It is safe to assume that the cornoler was the transposition of Roman fencing into medieval times, which survived thanks to the isolation that protected the Venetian lagoon from the disastrous collapse of the Roman Empire.

And was this school typical of the city of Venice alone?

Yes. There were also other schools of stick fighting around, for instance in Pisa. But fighting with the cornoler is typically Venetian and somewhat spread inland with the expansion of the mainland state. It also had the peculiarity of being accompanied by a particular form of boxing, in aid of the stick but autonomous as a discipline: the free hand made lunges, the Pugno de ponta vinitiano, as the Bolognese called it. It too was designed to fight side by side in formation, like the cornoler. A thousand years of warfare on the bridges of Venice had made the men of the lagoon accustomed to combat. And it was not just hand-to-hand combat: the authorities organised public training sessions with the crossbow, in which the male population was required to participate.

The birth of the Vinitian Pugno de punta

ŁEO: In 1191, Emperor Henry VI visited Venice. Welcomed with great pomp by Doge Enrico Dandolo, he was curious to see the famous ‘Venetian battles’, games between rival city factions that often turned into brawls, and organised games in his honour.

Sources of the time report that the emperor commented on the violence with which the two teams faced each other at such challenges with sticks and fists saying: “if it is a game it is too much, if it is a war it is too little”. As a guest, he acted as a judge of such contests, conceding victory to the Nicołoti (fishermen's team) because although they had lost the games he felt they had behaved more honourably than the Castełani (arsenal team). With the passage of time, also to reduce serious injuries and casualties in such urban battles, the authorities restricted the use of the stick. They switched from the cornoler to the Venetian Boxing or Venetian Fist, characterised by lunges and other techniques for fighting in close formation, which was excellent for brawls on the bridges and streets of a city.

It was not an entirely new discipline for the Veneto people, as they already practised a particular form of ritual boxing with the aid of dumbbells in ancient times.

MAS: The innovative element of this technique is precisely the use of straight punches. In the Middle Ages, boxing was still centred on the side punch, as it traced the movements of fencing therefore based on the hammer fist or mace. They practised the same movement as they did with the sword and it was safer for the hand to throw than the knuckle or straight punch.

ŁEO: Boxing since ancient times was characterised by circular punches, with the exception of the sagittal. The use of knuckle punches began with modern boxing and the spread of gloves, again for safety reasons because if I make a mistake in throwing a knuckle punch I hurt myself much more. The peculiarity of Venetian boxing is precisely that it is based on toe punches: in advancing with a united front it is much more usable. And this is very similar to the gladius fighting techniques of the Roman legions. With the left hand pointing towards the face in the same way as holding a shield.

All this allows us to dispel a myth, hard to die, of a Venice inhabited by merchants unaccustomed to weapons who took advantage of their immense wealth by employing ‘mercenary armies’.

ŁEO: Let us make things clear: Venice has always lived off its arms. The extensive recourse to captains of fortune came later, from the 16th century [when the Republic had already existed for almost 800 years, ed], and only for mainland affairs. All states at the time resorted to captains of fortune, Venice simply being very rich could afford many and the best. There was never a Capitano da Mar who was not Venetian, just as the members of the navy were Venetian.

MAS: The Republic of Venice subjected mercenary captains to a thorough examination to assess their technical skills and ability to deal with contingent situations. The examination was structured in introductory and practical questions, a real job interview!

Examples of introductory questions could be previous experiences in war, specifying places, factions and periods of service. The role held (captain of ordinance or mercenary company), the methods of maintaining discipline among the soldiers, and knowledge of the drum signals needed for different situations.

A practical question could be: ‘You are in the countryside with our soldiers. The enemy is nearby, and they outnumber you. You must save yourselves without fleeing, but fortify a position so that you can face him. Around you is countryside on one side, a river on the other, a forest and a hill. Which position would you set up camp so that you can attack the enemy while remaining safe?’

A methodological approach to the organisation of things of war, then.

ŁEO: Vecio mio, we are talking about a nation whose capital has never been invaded in 1,200 years of history. An achievement also thanks to the attention that Venetians paid to the military arts. Many historians seek the most varied explanations for Venice's impregnability, such as the presence of the lido. But we have countless cities with the same peculiarities from that point of view, so there is something else going on: the wisdom of government, of a group of people evolved in a particular context over millennia.

They bicker on a daily basis, but the moment you attack them they become one. A lesson also for today where internal factions often harm the people of Venetia. So knowing that culturally there was a propensity to set aside differences in the face of an external enemy, even things like the town battles between Castełani and Nicołoti were accepted.

In its own way, the war of fists is also a particular form of dialectic that helps to maintain the martiality of a people.

MAS: Venetian martiality is distinguished not so much by a specific fencing technique, but by a deeply rooted ethos that puts the protection of the people and institutions before mere warlike skill. As in ancient Rome, where endurance and dedication to community were supreme values, the Veneti demonstrated an indomitable will not to yield, even in the face of overwhelming forces. The conflicts that the Serenissima faced were almost always decided once diplomacy had failed, as is evident in their motto: ‘Not by our will, but if war, war it is’.

A parallel to this can be found in the Roman tradition of sieges, which followed the rule that until the ram had struck the first blow on the walls, surrender was possible, but after that there was no mercy. The Venetian martial ethos, like that of the Romans, was not a matter of war for war's sake, but of fighting for a higher cause: the defence of a political and social order in which the people identified and firmly believed. In this, Venice is a worthy descendant of Rome.

ŁEO: Assuming it wasn’t the Romans who learned this from the Venetians!

We have made a very broad excursus on the medieval and renaissance period, what can you say about the current period?

MAS: We certainly have some sporting excellencies such as Bebe Vio, a fencer who is so good that she can beat even able-bodied athletes. Fencing continues to maintain a very high level in Venetia, with excellent schools.

ŁEO: Remaining in the sporting context, where nowadays the warrior spirit is freer to express itself, what is interesting is the great popularity of rugby in Veneto. So much so that the individual teams are excellences at international level, unlike the Veneto football teams when the exact opposite happens in the rest of Italy.

Rugby in the Veneto region is so widespread and of such a high level that in the hypothesis of having its own ‘triveneta’ national team, it could easily participate in international competitions without disfiguring itself. In the Italian national rugby team, in fact, the absolute majority of players are from Veneto or play in teams from Veneto. But they insist on playing matches in Rome, which I cannot explain... maybe if we played them in Padua we would win every now and then.

I like rugby so much because it has an ethic that makes it very similar to martial arts. I think the proliferation of rugby compared to football is the result of the particular cultural humus of the Veneto region, and has been the subject of interesting sociological studies.

Boxing itself, as in other martial arts, still has some outstanding athletes. There is no shortage of other sporting excellencies, such as Pellegrini in swimming and many others... of course, today it is more difficult to say which of these excellences are the result of the culture to which they belong and which depend on the resources and abilities of each individual, since the sporting disciplines themselves are much more standardised than they used to be. Certainly a lot of sport is practised in Venetia, more than in the rest of Italy. If we were a nation in our own right, we would be a small sports power as well as an economic one.

But how did the ancient Venetians fight? Was there a sui generis martiality?

MAS: Here I leave the floor to Leo, who is the expert.

ŁEO: Through the findings of the situlae, we can see the use of the axe, the spear and three orders of shields. Not dissimilar to how the Etruscans fought. Here, however, it should be pointed out that archaeological findings attest to the Venetian presence on the peninsula as early as 1200 B.C., i.e. 400 years before the first Etruscan traces. Let it not be said that the Veneti copied weapons from the Etruscans!

Let us always remember that the Veneti were not considered ‘barbarians’ by the Greeks, with the sole exception of the historian Polybius. Strabo, in describing the location of Noricum, uses the lands of the Veneti as references, thus the most distant of those usually known to the Greeks of the time. Moreover, they used to specify their name as ‘Veneti Adriatici’, an indication that they were aware of the existence of other Venetian populations, certainly the Anatolians but perhaps also the Baltics (Wends, Venedi) and the Armoricans of Brittany.

In any case, during the descent of the Celts into Italy, they defeated the Raeti and Etruscans, while the Veneti were never subdued, remaining locked in an interminable war alternating with long periods of peace. How did the Veneti manage to resist? Surely geography played a role, with several rivers cutting through the Venetian plain and thus acting as various natural barriers [as we have already discussed in a previous post, ed]. Rivers were not dammed, therefore prone to flooding and surrounded by swamps. We know that the Veneti were renowned as skilled navigators, including river navigators, and therefore knew how to move nimbly through these waters and marshes.

According to the 19th century historian Pietro Manfrin, the Veneti fought with short arms and shields, but also with cavalry. We also know that the Veneti were particularly good at breeding horses, which they sold abroad as valuable goods. So we have a population that could move nimbly along rivers but at the same time developed a well-trained cavalry.

Well, there are no direct sources attesting to this but I have a theory on this, based on putting together all this information known to us: it is possible that the Ancient Veneti carried out deep incursions into enemy territories by combining river transport and cavalry: a landing of cavalry troops on trampable terrain, over marshes and swamps. A strategy based on swiftness that would have enabled large dismounted armies, such as those of the Celts and Etruscans. If one day we were to have confirmation of this, we would be faced with a case more unique than rare in the history of the war strategy of the Ancient Ages, capable of further explaining the irreducibility of the Veneti in the face of invaders. Let us remember that Rome never invaded the Veneti either, but they were always allies. All their neighbours were eventually conquered by Roman legions.

Our time is running out. What conclusions can we draw from this journey into Venetian martiality?

ŁEO: Martiality only stigmatises a cultural relationship with the environment. It should not be justified by geographical circumstances alone: it is your cultural setting that generates what you do with your surroundings. The study of its martiality therefore provides an excellent insight into what is Venetian society, and any other, in its entirety. The Veneti today, like other European peoples, live in a crucial period where their traditions are in danger of being swept away. Rediscovering our martial spirit and translating it into sports and business competition is also a way of rediscovering a way of life that has always accompanied us and made us great.

MAS: I am confident that one day we will rediscover that greatness.

ŁEO: Me too.

And with that I'd say we can end on a high note. Thank you Danilo and thank you Marco Antonio for these testimonies, and Viva San Marco!

ŁEO & MAS: Viva San Marco, sempre!