Beyond the Nation-State

Nationalism in the Age of Caesarism

Why is state politics increasingly absurd and unstable? Why is the “democratic process” so unworkable? Why has geopolitics become so complex, multilayered, and unpredictable, compared to just decades ago?

We live in a world that is increasingly incomprehensible through the conventional XX century paradigm - not because of an increase in the complexity of world affairs, but rather in the inadequacy of the conventional view based on nation-states as units of political organization, both on an internal and international level.

In this article, we will present our own perspective on the current trends and developments regarding the nation-state as a model of governance.

We will first define it, giving an overview of its emergence and eventual assertion over other forms of political organization; then, by observing current trends and the overall civilizational course of Western civilization, we will provide our vision of the future, as well as the implications for ethnonationalist movements.

Before we begin our analysis, we need to clarify and define what we are talking about, and how we’re going to approach the subject. By criticizing the nation-state as a concept, we do not criticize nationalism as a principle, or the existence of Nations as such. Instead, we are critic of the modern assumption of associating the Nation to the State, an institution that is territorially defined and characterized by a bureaucratic structure that is omnipotent towards the Individual within a clearly defined territory.

The Nation-State

As a political entity, the nation-state associates the concept of the Nation (from the latin natio, “to birth”, referring to a group of people sharing a common ancestry, language and culture), to that of the State (a political organization with sovereignty over a clearly defined territory).

It usually presents the following traits:

Territorial Sovereignty: the nation-state has a clearly defined territory over which it exercises supreme authority, a right that is recognized both internally and externally;

Cultural Homogeneity: the nation-state promotes a shared national identity, language, culture, or ethnicity, aiming to foster unity among its citizens;

National Legitimacy: the nation-state draws its legitimacy from (theoretically) representing the will of the Nation;

Monopoly on Force: the nation-state has a monopoly on the legitimate use of physical force within its territory, with the aim of ensuring internal order and external defense;

Source of Law: the nation-state is the sole source of Law within its territory;

Social Contract: the individual is endowed with inherent individual rights that are protected by the State.

The modern nation-state - born from European modernity and popularized by the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars - is not the “default” model of governance common in most of history; even in the present-day it hasn’t been successfully applied in most of the world.

In the European context, associating nations to states that have total control over clearly defined territories is a relatively new development, being normalized only in the last 200 years. While modern polities exhibit legal pluralism (for instance, EU law has primacy over conflicting national law), since it is legitimised by its monopoly on force the state effectively retains its role as the source of law.

Before the XIX century, we can observe a different world.

Before, After, and Beyond Westphalia

The Medieval World Order

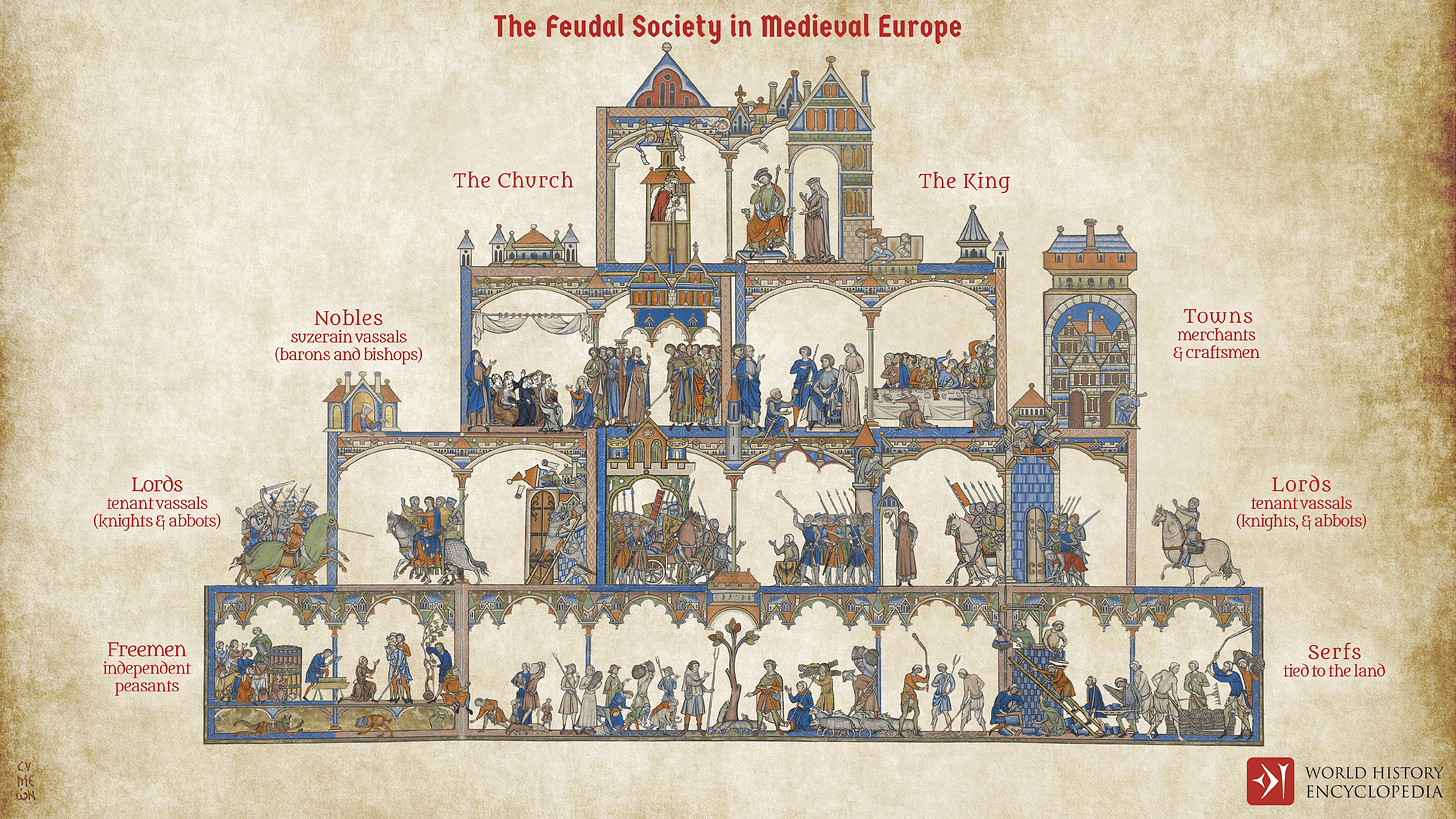

The pre-Westphalian sociopolitical order, typical of the medieval period, was characterized by a decentralized structure of governance. Power within kingdoms was fragmented, with authority divided among kings, local lords, the Church, and other local actors, creating a mosaic of overlapping jurisdictions and allegiances. Unlike the modern nation-state, sovereignty was neither centralized nor confined to clearly defined territorial boundaries. The Catholic Church, the feudal system, monastic orders, and merchant guilds operated across regions, creating networks of influence that linked disparate territories.

At the heart of this order was the feudal system, a network of personal relationships built on landholding and loyalty: lords granted fiefs to vassals in exchange for military service and fealty, binding individuals through mutual obligations rather than allegiance to an abstract state. Each noble enjoyed significant autonomy and wielded more practical power within his domains than the distant monarchs.

At the same time, “global” institutions claimed universal rule over medieval society: on one hand, the top of the feudal pyramid was represented by the Emperor, a figure claiming a universal and divinely sanctioned jurisdiction over all Christendom. This was not a state in the modern sense, or even an entity defined by rigid borders, but rather a symbolic and ideological entity characterized by unity, legitimacy, and a sacred mission to maintain divine order. Challenging this pole of authority was the Catholic Church, a transnational religious institution whose spiritual authority frequently rivaled or exceeded that of secular rulers. The pope claimed supremacy over Christendom, while bishops and abbots governed extensive lands and populations locally, serving as both spiritual leaders and temporal lords. The Church’s influence was not merely religious but influenced the laws, culture, and diplomacy of medieval Europe.

In the medieval world, borders were often undefined and contested, and individuals identified with - an owed their loyalty to - their local community, tribe, lord, or religious community rather than to the idea of a unified people or state (although local aristocracies certainly expressed forms of ethnic self-interest). The legal landscape mirrored this fragmentation: justice was administered through a patchwork of different systems, including customary laws, feudal courts, and ecclesiastical tribunals - often overlapping and competing with each other. This multiplicity of legal jurisdictions reinforced the decentralized nature of medieval governance, providing a degree of freedom - albeit chaotic - from the legalist excesses typical of the modern era.

In this world, transnational connections transcended political and territorial boundaries. Efforts such as the Crusades and the activities of religious orders reflected a shared identity that, at times, managed to mobilize medieval Europe to a degree that the modern system of nation-states can’t even approach.

The Sovereign State…

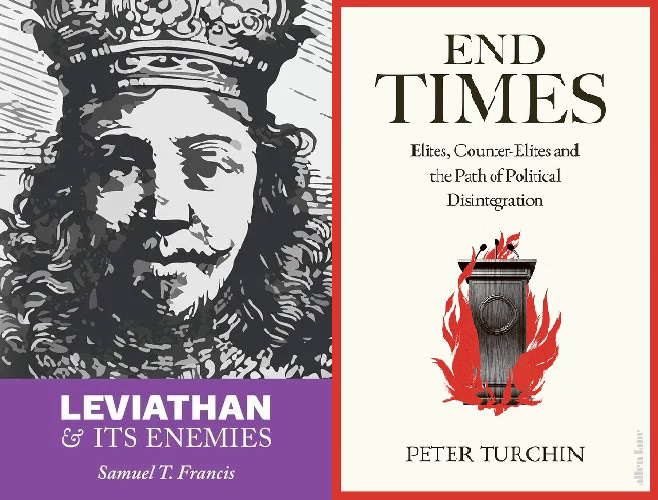

It is not clear when exactly the concept of the modern state first began, but signs of its conception as an idea can be traced in the works of thinkers like Niccolò Machiavelli’s Il Principe (1532), in which he introduced the concept of “National Interest” or Ragion di Stato (a term popularized by jesuit Giovanni Botero, lately), meaning the pursuit of power, security and wealth by a state, or Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan (1651), popular for its theory of the social contract and its support for absolutism. Generally, we can view it as a process beginning in the Late Middle Ages and completing its development with the French Revolution, or beyond.

Aided by technological developments favouring centralized political entities of a certain size - like gunpowder warfare and the printing press - the rise of the European nation-states took place within a medieval world order - the Ancien Regime. It wasn’t until the end of the XVIII century when the concept of the nation-state, as understood today, can be said to have been formalized as the norm in international relations.

The Treaty of Westphalia (1648), which ended the Thirty Years’ War, marked a turning point in the organization of political power, formalizing the principles of state sovereignty - meaning that states had supreme authority within their territorial boundaries and were free from external interference in their internal affairs. This framework laid the groundwork for modern international relations and would aid the emergence of the nation-state, defined as a political entity wherein a centralized government represents a population united by shared language, culture, and ethnicity - a Nation - within specific borders.

It is important to recognize that Westphalia emphasized the sovereignty of monarchs over their own kingdoms, rather than that of nations. The latter would become relevant as an ideological crutch to the European states in the turn of the XIX century, when the French Revolution and the rise of modern ideologies would gradually replace the typically medieval means of establishing legitimacy - such as the divine right of kings or the feudal system - instead introducing the ideas of popular participation in the political process as new pillar of the ruling class’ legitimacy.

During the same period, the concept of the individual as citizen gained prominence, moving away from subjects bound by feudal obligations and towards individuals vested with natural rights and responsibilities (as in the idea of the social contract) within the framework of the state. These principles laid the intellectual foundation for viewing the inhabitants of a state not merely as subjects but as autonomous actors endowed with inherent rights.

Sounds good, right?

…and the Enslaved Individual

As the last 200 years show, despite the idealistic notions of international law and human rights, the modern citizen is endowed with rights only in the context of the jurisdiction of the State as the sole authority endowed with a monopoly on both Force and Law within a specific territory. Thus, while rights can be granted by a state, they can also be revoked or ignored arbitrarily at any point and for whatever reason, regardless of how democratic any form of government claims to be.

The rise of the modern state can be interpreted as the gradual abolition, absorption or subjugation of any institution that could compete with the state, or even come between this new Leviathan and the individual. No doubt, this was done through modern ideologies - in the name of “democracy”, or to better manifest “the will of the nation”, or to cancel “oppression”. Thus, the nobility was castrated, the Church was persecuted, and local languages, customs and traditions were repressed in the name of “national unity”.

It is interesting to note that, to progressively increase its own power, the modern state (represented by the new bureaucratic or managerial class) didn’t hesitate to “betray” the institutions that once served as its basis: the age of Absolutism saw the repression of the Nobility and the Church by the Kings, while the French Revolution saw the Kings being removed as obstacles to the sovereignty of the Nation itself.

Similarly, the XX century saw the concept of the Nation redefined or outright denied, removing the last barrier to complete plutocratic and bureaucratic control over the Individual. The modern state, having dismantled every institution capable of resisting its influence, now denies the very existence of the very population it is meant to safeguard, with its managerial class labeling national identities as “dangerous” and “divisive,” while pursuing policies designed to erode it.

Case in point, the most recent trend in the evolution of nationalism - especially from European right-wing parties - is to try to extend the umbrella of nationalism to anyone willing to live and work within the territory of the state and adhere to “national values”, especially to those that are not even part of the Nation itself by definition. This ideological oxymoron, dubbed civic nationalism, is yet a further escalation of the totalitarian homogenizing tendency typical of the modern state, which is now desperately trying to evoke the fleeting loyalty of the populations living within its territory.

Due to this, continued support or passive adherence by ethnonationalists to the model of the nation-state as a given assumption risks, at best, of jeopardizing their efforts and, at worst, of being counterproductive, in a world in which nation-states are increasingly becoming shells of their former selves.

Beyond Westphalia: The False Dychotomy of Nationalism and Globalism

The modern world faces a paradox: the increasing inability of nation-states to manage their own affairs coincides with the decline of global institutions as effective frameworks for governance. This dual failure is reflected in the recent metamorphoses of both nationalist and globalist initiatives.

At first glance, nationalism and globalism appear to represent diametrically opposed worldviews. Nationalists, heirs to the Cultural Right - champion local sovereignty and cultural uniqueness, while globalists - mainly from the Cultural Left - advocate for interconnected economies and centralized regulatory institutions on a global scale.

Despite these different objectives, both are grounded in assumptions about the role of the state, of the individual, and the nature of rights, that are typically modern, as both seek to exert total control over society - just on different geographic scales.

It is not a coincidence that these seemingly competing frameworks are actively supportive of the current global order, and have become increasingly interdependent during the post-WW2 period: nation-states benefit from international cooperation to ensure their stability and territorial control, while global institutions rely on the total authority of the states to enforce their influence over the latter’s territory.

We can thus conclude that the apparent struggle between these “ideologies” is not of opposing visions, but rather a competition for influence between different actors withing the same system - global in scale yet increasingly fragmented and liquid.

The Globalization of Nationalism

Nationalist movements, traditionally focused on preserving local identity, are increasingly adopting “globalist” methods to overcome their scale limitations: leaders and parties collaborate across borders, forming international alliances and sharing tactics and strategies. The internet has accelerated this trend, enabling the proliferation of universal slogans and symbols.

This "globalized nationalism" often contradicts its foundational principles by eroding cultural and national distinctiveness in favor of a shared, transnational framework. This has resulted in nationalist movements lacking deep roots in specific cultural or historical traditions - unlike their XX century counterparts. Instead, they operate within a broader ideological and methodological framework that mirrors the very globalist structures they oppose.

The Fragmentation of Globalism

Meanwhile, the influence of global institutions is undermined by new challenges, as geopolitical tensions, economic disparities, and supply chain disruptions have exposed the fragility and impotence of the former. In addition, the lack of even the basis for a unified global culture has drawn backlash to the explicit aims of globalists to erase cultural uniqueness from all over the world.

These factors have led to a re-localization of globalist initiatives. For example, multinational corporations are either re-rooting themselves within the territories controlled by global hegemons like the US or China, or are establishing regional hubs to adapt to diverse local conditions.

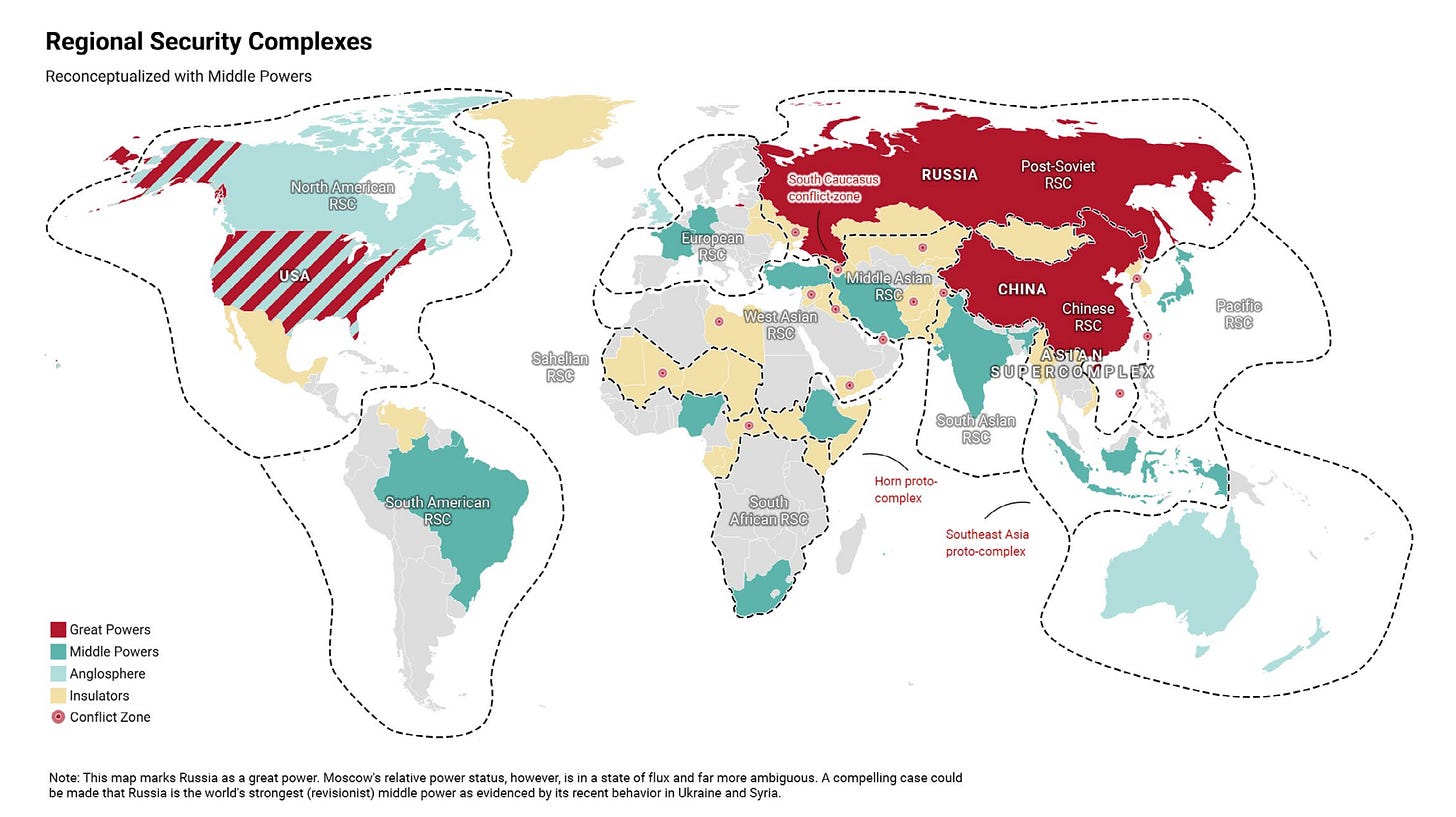

This trend undermines the centralizing ambitions of globalism by creating a fragmented (yet still global) landscape of competing spheres of influence dominated (politically) by major powers like the United States and China, but in practice increasingly influenced by - and reliant on - emerging para-statal actors.

As globalism adapts to this new reality, it paradoxically accelerates the creation of a global order characterized by overlapping spheres of influence and inter-domain competition between non-state actors.

Limits to governance

Additionally, we need to consider the possibility that - for reasons not clearly apparent - there must be limits to governance that vary based on a plurality of factors.

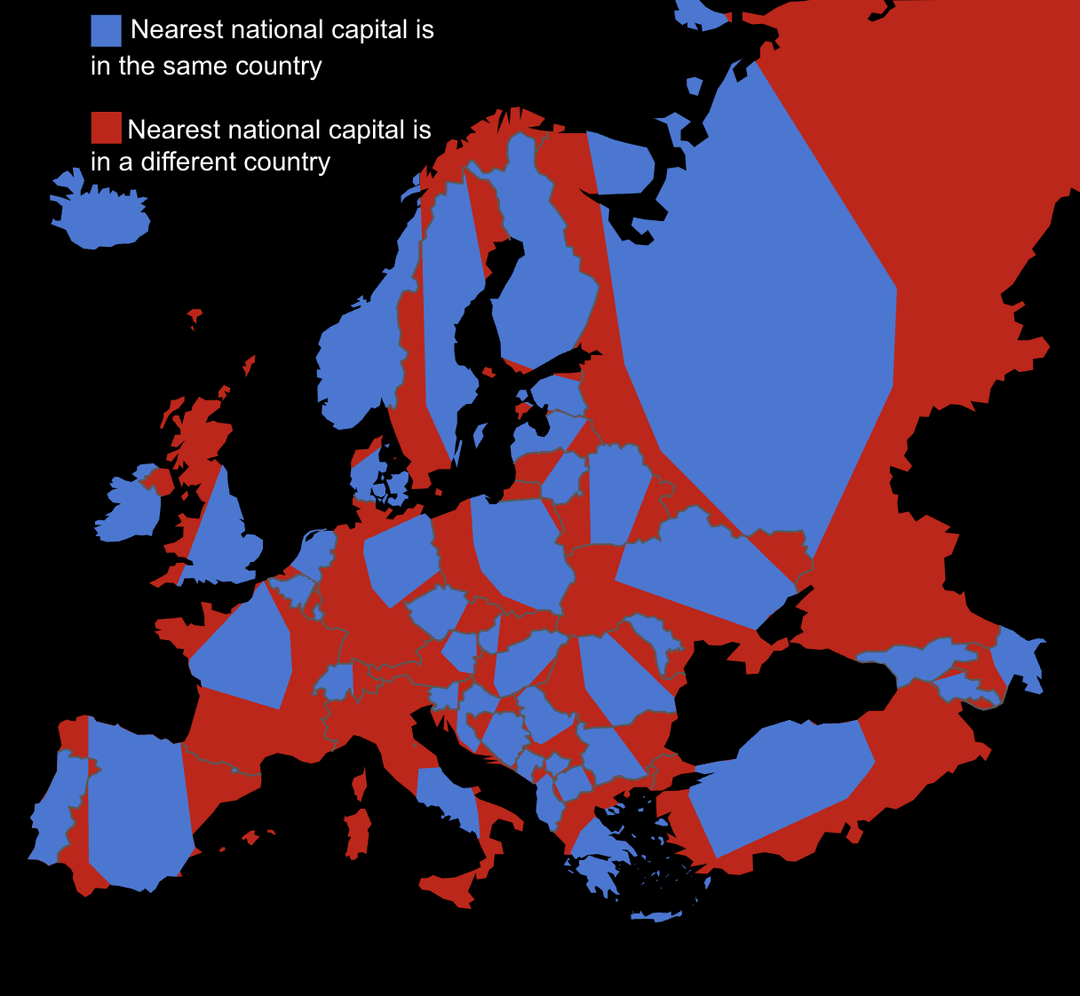

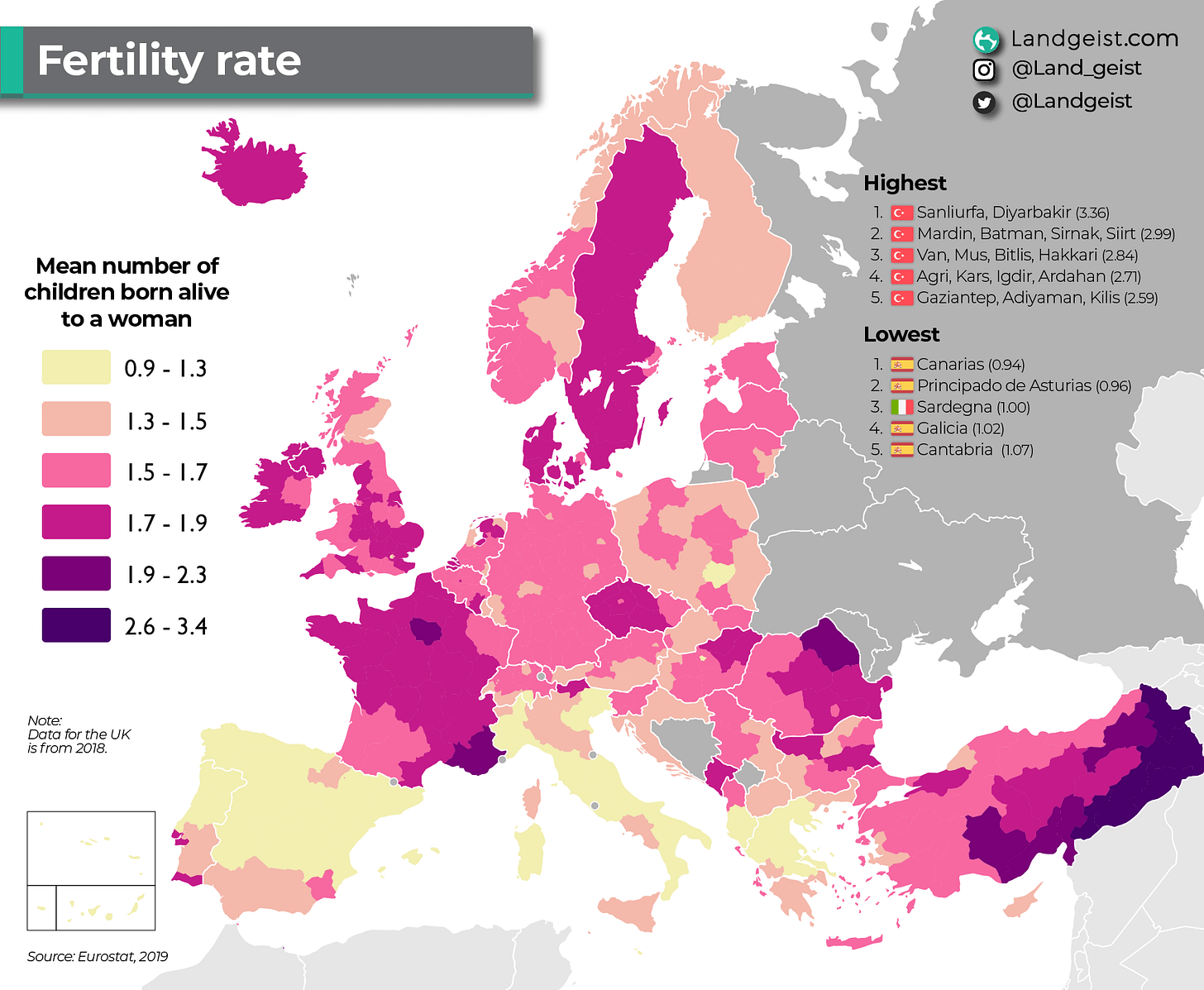

For example, take a look at the following map:

This map, showing the territories of the various European states that are closer to their national capital than to the capitals of other states in blue, with more “distant” territories in red, surprisingly highlights most of the secessionist or autonomist movements of each nation-state - at least in Western Europe, where state formation was far less considerate of actual ethnic self-determination, and was instead driven by geopolitical competition.

Of course by itself, doesn’t mean anything substantial -the location of the capitals is not uniform in each state- but it provides an interesting avenue to reflect, as it seems to evoke the existence of an inherent limit to governance. More than by geographical distance, such a limit would logically be influenced by factors such as transportation and communication technology, degree of urbanization, the civilizational “stage” at which a certain society currently is, and the degree of autonomy enjoyed by local governments.

Besides these variables, at its core this concept leads to the idea that there may be a hard limit to what can be defined as a people, similar to a kind of “Dunbar number” for Nations, a kind of inherent limit as to what can be defined as a single People, beyond which it tends to divide into separate peoples.

If there is indeed such a limit, it stands to reason that the extension of political control over a bigger and bigger scale - such as the creation of a civilizational, or global state - implies an increase of both geographical and institutional decentralization. In other words, the bigger in scale a political union is, the more it has to rely on smaller/more limited actors to exert its will.

The causes for such a limit are difficult to even conceptualize in a single article, but we can observe that, throughout history, each epoch has been characterized by more or less centralized forms of governance.

Centralization and Decentralization

Over the course of history, we can observe periods characterized by centralization or decentralization, patterns that usually impact all domains of human existence.

Centralization, characterized by the consolidation of power, resources, and decision-making, usually creates large, cohesive entities - empires, bureaucracies, or economies. Conversely, decentralization distributes these elements among smaller, more autonomous units, increasing overall diversity and the agency of individuals and specific groups.

These trends are not confined to politics or geography alone, as there are different domains in which these trends can occur:

Territorial centralization sees the rise of expansive states, while its opposite results in fragmented city-states or tribal groups.

Social centralization manifests in the dominance of a specific class over the whole society, whereas decentralization permits competing traditions, localized governance, and is reflected in a balance of power between different classes.

On a more general level, these dynamics can either allow individuals to be relatively autonomous and have agency in the society they inhabit, or be dependent on a central authority for their survival or social status.

Centralization in one of these domains - territorial, social, individual, and others such as economic, technological, and military - usually leads to centralization in others, but that’s not always the case: sometimes these twin developments can occur simultaneously in different fields of human existence.

The most visible (but not the only) metrics to explain why some epochs tend towards centralization or decentralization is technology and the social systems employed to manage society but - as we will see in the next section - they are not the only ones.

The crisis of the nation-state as a model

Today, while the facade of relevance of the nation-states seems to hold, various trends and long-term developments point to a future in which the nation-state will be increasingly incapable of exercising is prerogatives. Here we will try to list them, from the most fundamental and occult to the most contingent and visible.

Civilizational trends

According to Oswald Spengler’s model of civilizational development, Western Civilization is headed towards the formation of a civilizational state whose traits are fundamentally different from those of the nation-state-based global order, meaning that such a state will not resemble a modern state on a global scale, but rather a universal framework in which competition between non-state actors will follow different rules from the present.

The transition from Culture to Civilization, which in the Western context occured at around 1800, has been characterized by a fundamental erosion of the metaphysical foundation of Western society. In the cultural phase, western institutions, values, and creative expressions were unified and sustained by a shared metaphysical vision or symbol. This gave rise to culture-specific forms - political, economic, religious, and artistic - which embodied the symbolic and spiritual essence of Western Culture.

The transition from Western Culture to Western Civilization marked the increasing mechanization and artificiality of these forms, reducing them from living expressions of a shared meaning to functional and utilitarian mechanisms. This shift reflected the dominance of the so-called "money-spirit", according to which economic considerations supersede all others, infecting all aspects of human existence.

Inevitably, as Western Civilization progresses, all western-specific forms will begin to break down, and domains that were once distinct in their own right will start to lose their boundaries, united into a utilitarian framework: politics becomes inseparable from economics, with decisions increasingly dictated by financial elites and technocratic rationality. Religion, once a source of profound meaning, becames either a private matter or a tool for political manipulation, and art devolved into repetition or commodification. The infiltration by money-spirit of every aspect of Western Culture has - and will further - make power more liquid and formless.

According to Spengler, this process will culminate in the complete erosion of symbolic unity and the atomization of society: individuals, disconnected from the larger metaphysical vision, will prioritize personal interests, weakening the ability of institutions - by now shells of their former selves - to command loyalty and maintain social cohesion. As the barriers between domains collapse, the mechanisms of governance become less capable of upholding distinct prerogatives. This will result is an increasingly unstable society, unable to resolve problems through institutional means.

The endpoint of this transition is Caesarism, the concentration of authority in the hands of charismatic individuals who prevail over the hollowed out institutions of Civilization by wielding power not through legal or institutional legitimacy but through sheer force of personality, representing a return to archaic power dynamics.

What does this mean in practice? On one hand, the advent of Caesarism implies a sort of political centralization, but is it really the case? At its core, the figure of the Caesar is concerned with maintaining personal power rather than administering every detail of how people live - unlike the modern state. His rule is pragmatic, not progressive or informed by ideology.

Furthermore, the loss of symbolic unity typical of the Civilization period - which causes the erosion or subsuming of its cultural forms - leads to internal loss of institutional coherence, making that any attempt at total rule impossible. Instead, power will become increasingy personalistic and reliant on negotiation with elite factions.

Thus, behind the facade of strength and unity projected by the figure of the Caesar, the underlying trend of fragmentation of the Civilization will progress unabated, leading to compromises and sharing of power with non-state actors to maintain the appearance of control, as imperial authority comes to rely more and more on what are essentially emerging institutions in their own right. Over time, this instability would become apparent through factionalism, civil wars, and institutional decentralization.

An example of the process we just described is the Roman Empire itself, the culmination of Classical Civilization that - in a few generations - revealed itself as a mere shell of a fragmented Civilization.

Taking the example of the nation-state, its fate during this transition is emblematic of the overall decline of Western forms: despite having started as the organic manifestation of the nation’s will, the association of the latter to the bureaucratic structure of the state made it so that new, artificial national mythoi could be constructed through political and military power and propaganda. In the transition to Civilization, the nation-state didn’t even need to base itself on an actual nation anymore, and instead came to actively deny ethnocultural realities within its borders.

For this reason, we argue that the nation-state stands as the main obstacle to true European ethnic self-determination, and will soon lose the facade of being an organic expression of ethnocultural identity, and instead serving as a bureaucratic prison that serves plutocratic and globalist interests, a mediator between competing non-state actors, with the only function being to “manage” the population within its borders.

National “leaders” claiming to act in the interest of the Nation are either put in power by occult interests, or are beginning to hold an authority that bypasses the legitimacy of traditional institutions, operating instead through networks of influence that trascend national or institutional boundaries.

The prerogatives of the nation-state are already being hollowed out, as power becomes more fluid and diffused across non-state actors: multinational corporations, global financial systems, private military companies, and transnational organizations increasingly take over roles once reserved for the state. These entities will operate within the emerging Western Imperium, the global framework of interconnected but competing forces that Spengler predicts as the ultimate stage of Western Civilization.

Sociological and geopolitical trends

More visible trends are historical, relating to the rise of the nation-state itself and pertaining to sociology and geopolitics, separate fields but connected in how they impact the nation-state today.

Central to the nation-state’s historical success has been the managerial class - an administrative elite responsible for organizing and administering complex social and economic systems. This class rose to prominence during the industrial era, as nation-states required centralized authority to manage resources, enforce laws, and regulate expanding economies. Gradually, it came to monopolize power within centralized states and multinational corporations as it evolved from a tool of governance into a self-perpetuating class focused on its own expansion.

However, its dominance is eroding due to structural inefficiencies and the rise of competing power structures: bureaucracies have grown bloated and inefficient, imposing regulations that often stifle innovation and alienate citizens. The managerial elite, detached from the realities of the working and middle classes, is perceived as self-serving and unaccountable, resulting in widespread discontent and the rise of populist movements in the West.

Secondly, the proliferation of higher education has created an oversupply of aspiring elites, leading to intense competition for the few positions available. This overproduction of elites causes not only internal competition within the managerial class, but also diminishes its cohesion, as many educated individuals fail to find meaningful roles in the existing power structure, and eventually form a counter-elite that could either come to conflict with the entrenched elite or find a role in emerging economic, military or religious institutions. The latter would both compete for influence and threaten to further break the monopoly of the state as the providers of key services.

While autonomous military and religious institutions have not yet emerged as viable alternate “career paths” for members of the elite (althrough we are seeing the first instances of them in PMCs and religious and ideological movements), multinational corporations - which have traditionally been supportive and benefited from the managerial class’ supremacy - are already playing a role in undermining the current global order, operating with an autonomy that rivals or even surpasses that of small nation-states.

The system of incentives driving the behaviour of corporations is fundamentally flawed: in the short term, they are incentivized to weaken nation-states by pushing for deregulation and other concessions that maximize profits, but ultimately this will hollow out the ability of states to govern effectively, contributing to the destabilization of the global system on which corporations rely for their stability and profits.

These corporate empires, often controlled by powerful families or boards, already exert substantial economic and social power, having come to creating “corporate fiefdoms” within the territories of nation-states, mirroring the way ecclesiastical immunities granted to monasteries and bishops in the Middle Ages gradually eroded the authority of monarchs. The decline of the managerial class and the emergence of new non-state actors will erode the centralized authority of the nation-state, reliant on bureaucratic supremacy for the maintenance of the monopoly on Force and Law.

Externally, the European nation-states, safeguarded from external competition by the security granted by the Cold War and later by the rise of the unipolar world order led by the US, are now beginning to wake up to reality: History never ended, and now regional hegemons capable of mustering resources and manpower on a scale unmatchable by single nation-states are beginning to loom over the geopolitical horizon. As mentioned earlier, globalization will likely redirect within civilizational blocs, each led by a regional hegemon, forcing sovranational coordination.

The convergence of these trends points to the emergence of a new global system, in which power is decentralized and fragmented, with overlapping authorities - global conglomerates, transnational organizations, local communities, private armies -coexisting and competing. The nation-state, once the dominant actor in global affairs, will become one among many actors, its prerogatives increasingly constrained by external and internal forces. This does not imply its disappearance, but rather its transformation into weaker entities within a larger mosaic of governance.

Demographic trends

Turning now to more visible developments, we can observe first of all demographic trends, which are undermining the very raison d’etre of the nation-state and are reinforcing each other: the Depopulation of the Native European populations, and Mass Immigration from the rest of the world.

Historically, the nation-state emerged in a period of high fertility, where large populations were essential for economic growth, military defense, and for propagating a shared national identity. This model relied on the idea of the "citizen-soldier" - an individual deeply tied to the state through obligations like military service and the promise of rights and protections in return. However, as fertility rates have already declined in the West (but also elsewhere, at different rates), the native European population will shrink, eroding the foundation of the nation-state and even changing the way individual identity will be constructed.

First of all, depopulation weakens the ability of centralized governments to mobilize manpower, whether for military, economic, or administrative purposes. Without the large populations needed to sustain expansive state functions, the role of the individual within the nation-state diminishes. State prerogatives such as conscription, public education, and welfare will become harder to maintain, leading to a retreat of individuals from “high politics” and the ideals that defined the modern nation-state.

In a depopulated future, governance may fragment into smaller and localized units that focus on immediate and more practical concerns rather than abstract, national-scale projects, reflecting a shift in loyalties from the abstract "nation" to local identities tied to regions, ethnic groups, or even familial clans - while universal forms of identity become possible once more, based on religious and racial affinities. This mirrors the decentralized nature of authority during the medieval period: individuals engaged more directly with local power structures like feudal lords, guilds, or religious institutions, while pan-European projects and institutions were able to mobilize local actors effectively when needed.

Economically, depopulation will incentivize a return to smaller-scale, localized production, as maintaining global supply chains or national-scale industries becomes less feasible. Technology and global interconnectivity could mitigate some effects of depopulation, as automation might replace lost labour and digital tools could maintain centralized governance even with smaller populations. Yet, these solutions may not be sufficient to sustain the nation-state in its current form, particularly in functions that rely on raw manpower - which are the most essential, like the military and fiscal aspects of modern governance.

Another demographic trend, and perhaps the most impactful on the long-term, is Mass Immigration. In the West, it is already bringing about profound and lasting changes to the ethnic composition of core European territories, potentially for decades to come. This phenomenon, is already eroding the ideological foundations of the nation-state, since the latter draws its legitimacy from the fact that it theoretically represents the shared Common Good of the Nation, and that it is supposed to be a collective framework in which all citizens theoretically participate and benefit.

The increasingly multiethnic nature of Western states will fracture this “Common Good” even more than it already has. The Aristotelian concept of philia - the necessary social cohesion and mutual trust of a polity borne from ethnocultural homogeneity - will disappear and, in its place, ethnic tribalism will reign. The divided populace will be less likely to perceive itself as part of a “nation”, lowering trust in public institutions, which in turn will devolve into clientelistic structures that serve particular interest groups rather than the collective that doesn’t exist anymore.

As a result, a multiethnic West - like all multiethnic societies - is likely to become more authoritarian and prone to internal violence, with diminished social trust and a growing alienation from the state. This erosion of loyalty will incentivize individuals to seek alternative institutions that better align with their identities and offer a sense of belonging.

Technological trends

The nation-state emerged - at least in part - thanks to several technological developments that favoured centralization:

Gunpowder weaponry, whose cost of adoption was bearable only by bigger political organizations, better able to coordinate resources effectively, incentivized the adoption of mass infantry formations;

The printing press, which initially broke the monopoly of education and knowledge transmission held by the Church, allowed the State to form its citizenry though education, early media like journals and pamphlets, and propaganda;

Advances in navigation (compass, astrolabe) and shipbuilding during the Age of Exploration enabled states to project power globally, and to amass wealth and resources to finance state institutions;

The Industrial Revolution created economies that required efficient governance and administration, favouring the rise of centralized states and resulting in improved transport and communicationn technology (telegraph, railroads).

To assess the impact of recent technological developments on the future of the nation-state, we first need to further clarify the issue of centralization and decentralization.

Centralized institutions are usually dependent on technologies and systems that demand significant coordination, resources, and hierarchical organization. In contrast, epochs of decentralization see the development of technological or social innovations that are more accessible and less dependent on large-scale coordination to be effective. As a consequence, they empower decentralized actors and make central control less effective or desirable, leading to a diffusion of control and an erosion of the dominance of centralized entities. Some examples include private transportation vessels, crossbows, medieval castles, and cryptography.

Notably, the same technology can support centralization or decentralization depending on the historical context. For example, iron smelting initially broke the monopoly held by bronze-based armies and allowed decentralization, but its ease of production later allowed the rise of mass armies and huge empires like Persia and Rome, as military tactics and logistics caught up.

Recent technological innovations are just now beginning to incentivize decentralization, impacting the ability of nation-states to maintain the monopoly on Force and Law, and thus to operate their core functions.

First of all, the Internet: initially developed as a military tool, it has since evolved into a profoundly decentralizing force, enabling individuals and small groups to challenge centralized institutions, spread ideas and knowledge, and coordinate independently. With its public adoption having started just a generation ago, we have yet to bear witness to its full historical impact. On the long-term, just as the printing-press broke the monopoly of the transmission and diffusion of knowledge held by the Catholic Church, the internet will break the monopolies held by the state over communication, education, and more.

Related to the internet, the recent emergence of Blockchain technology will - granted it won’t fall under centralized authority - allow individuals and non-state actors to operate, trade and communicate without the state’s institutions as intermediaries.

In more practical fields, the development of 3d printing will allow for individuals and relatively small groups to manufacture goods without the significant capital investments typical of industrial manufacturing. The same could be said of decentralized energy production, which is becoming incresingly feasible through innovations in renewable energy technologies and energy storage, which will reduce the reliance of communities and settlements on centralized infrastructure.

The recent proliferation of drones in global conflicts reflects a shift in military incentives towards tactics that reduce direct human involvement and, in many cases, operational costs. This is evident in asymmetric warfare, where drones enable smaller or less resource-intensive forces to challenge traditional state militaries. Still, while drones lower the immediate costs of deployment, their development, maintenance, and vulnerability to countermeasures like electronic warfare are still limiting factors.

Artificial intelligence - or at least what the general public understands as such - is already revolutionizing most managerial and service jobs, and could be employed to substitute the bureaucratic needs of states and businesses. As other technologies mentioned, it will likely lower the human capital needed for non-state actors to operate.

The Shape of the Future

So far, we described trends and developments. Predicting the future is another matter, which we can’t reliably do - but we will try anyway, with some caveats.

First of all, historical trends are only visible in hindsight, often hinted at by temporary solutions to immediate crises that, over time, consolidate into recognizable practices, laws, and institutions. Thus, while the nation-state will not vanish abruptly, its transformation and/or replacement by new models of governance is inevitable.

Before the advent of a fully decentralized neo-medieval structure, the West is likely to experience an “imperial” phase characterized by the emergence of large-scale political unions that consolidate their power over vast territories - yet simultaneously base themselves on non-state actors, laying the groundwork for decentralization.

In the future, sovereignty will no longer be territorially bound, and will instead fragment across regions and societal domains, with overlapping spheres of authority and influence commanding each individual’s loyalty. Governance will be shaped less by unilateral enforcement and more by negotiated power dynamics between actors - state and non-state alike. Such a framework will serve as the organizing principle that will replace centralized states, allowing non-state actors to operate, compete and provide services within a common framework.

The current managerial elite, which dominates the current system, will lose its supremacy as the structures it relies on falter. New actors - corporations, PMCs, local communities, religious institutions and ethnic networks - will assume the roles once monopolized by the state.

A similar development took place at the end of Antiquity, which can be traced as far back as to the founding of the Roman Empire: this development marked the initial breakdown of the institutional forms of Classical Civilization and the emergence of neo-archaic institutions - initially as crutches to imperial authority, and later as powers in their own right.

There are several possible scenarios for this transition in the future West, depending on its smoothness and the scale of global coordination:

Imperium Mundi: A politically unified global order, achieved through military or diplomatic means, where competition occurs between diverse actors operating within the system. This would resemble the Roman Empire, where centralized structures coexisted with significant local autonomy.

Multipolarism: A global order based on collaboration among hegemonic continental powers, each maintaining loyalty from non-state actors within their civilizational sphere. This scenario would mirrors the European balance of power after the Congress of Vienna.

Gradual Transformation: Nation-states survive in form but gradualy lose their monopolistic prerogatives, competing for influence on equal footing with emerging non-state actors. Think of a gradual dismantling of the Westphalian paradigm.

Global Disorder: A complete collapse of nation-states, resulting in fragmented governance akin to the feudal anarchy of the IX-X centuries or the collapse of Late Bronze Age civilizations.

Regardless of the scenario, decentralization will continue as the underground trend, shaping the trajectory of global governance. Each path will lead to the same endpoint - a decentralized, fragmented order - albeit through different timelines and degrees of instability.

The old order - characterized by centralized liberal democracies and welfare states - will likely not survive the mid-21st century without some kind of adaptation or breakdown. In its place, a decentralized and contested structure will emerge, where power is fluid, dynamic, and dispersed among multiple entities.

Nations beyond the Nation-State

The decline and eventual end of the nation-state will not mean the end of nations, as the latter existed long before the nation-state, and will exist long after it has gone.

Rather, it creates an opportunity to rethink the relationship between the individual and the state, especially in rejecting the homogenizing tendencies typical of the modern state.

From its inception, the nation-state sought to eliminate institutions that mediated between the individual and centralized authority, dissolving regional, ethnic, and communal bonds in favor of uniform citizenship. While this model enabled states to consolidate power and modernize, it also alienated individuals from their organic communities in favour of ideologies or artificial concepts of nationhood.

We do not think it is a coincidence that the very success of the nation-state in creating a centralized framework - connecting national identity to the institution of the modern state - has led to an erosion of the nation itself, cheapening its essence and reducing it to a shallow construct detached from any ethnocultural reality.

Which Nationalism, then?

In the past, and even in the present, nationalists everywhere have had the objective of creating or furthering the creation of a state that would safeguard and affirm the interests of their own nation. It makes sense, but does it actually work in the present?

As ethnonationalist Venetians, we have no doubt that if tomorrow - through some miracle - Venetia were to become an independent state, ethnically homogenous and with strong borders, it wouldn’t actually solve anything: immigration would still be promoted by elites interested in profit, while the root causes of cultural degeneration wouldn’t be addressed.

Instead of continuing to play the same old game of national politics, intent on some kind of “national revival”, European ethnonationalist movements need to recognize both the tactical and strategical necessity of adopting a “tribal” perspective - more compatible with the increasingly global - yet fragmented - future western society. We have already proposed some ideas for ethnonationalist tactics without state support, in our article on Remigration, but there are some other practical implications of the future we describe for ethnonationalist movements.

The question of whether to engage in politics is a misleading dichotomy. It is not a matter of whether to engage with politics or not, but rather of how to do it. Political engagement should occur within the framework of a full-spectrum strategy, where influence is pursued synergistically across multiple domains. For an ethnonationalist movement, this could mean lobbying and leveraging local political parties and issues to promote specific ethnic interests.

For those with the resources, capabilities and willingness to do so, another angle of pursuing influence could be to - again - leverage the increasing formlessness of power and permeability of different domains to aim at obtaining influence at a global (or imperial) scale, bypassing traditional institutions.

For online efforts, the use of English - the western lingua franca, like it or not - is not optional but essential for communication and coordination with potential “foreign” counterparts who may, in some cases, be more receptive to the cause of ethnic self-determination for a particular people than the latter’s “compatriots”.

Finally, the eventual decline of European nation-states will have an impact on the way Europeans identify. When you share legal citizenship with non-Europeans, and most of the services you benefit from don’t come from a state, what defines who you really are? Inevitably, ethnic identity will separate from the administrative entities known as nation-states, and look to actual identities that - in some cases - have been neglected during the processes of national “unification” during the XIX century.

However, an increasing obsolescence of “national” identity - along with the shared developments discussed in this article - will likely incentivize a sense of pan-European ethnic self-awareness. In fact, the former are a prerequisite for the affirmation of the latter.

Any pan-European sense of collective self must be based on ethnocultural reality, the only bedrock on which any organic identity can be founded. This implies not only a criticism of the nation-state, but also of institutions like the European Union, or any purely geographical definitions of Europe as a continent, as they constitute either arbitrary separations of brother peoples, or inclusions of non-European groups into the collective European heartlands. Any attempt at basing any pan-European identity on existing institutions is fallacious at best, and counterproductive at worst.

The nation-state certainly had its role in a specific historical and civilizational context, but now it must give way to new modes of governance and political organization. This is yet another reason why we, as The Third Venetia, are so keen on parallel institutions as a practical path forward.