Introduction

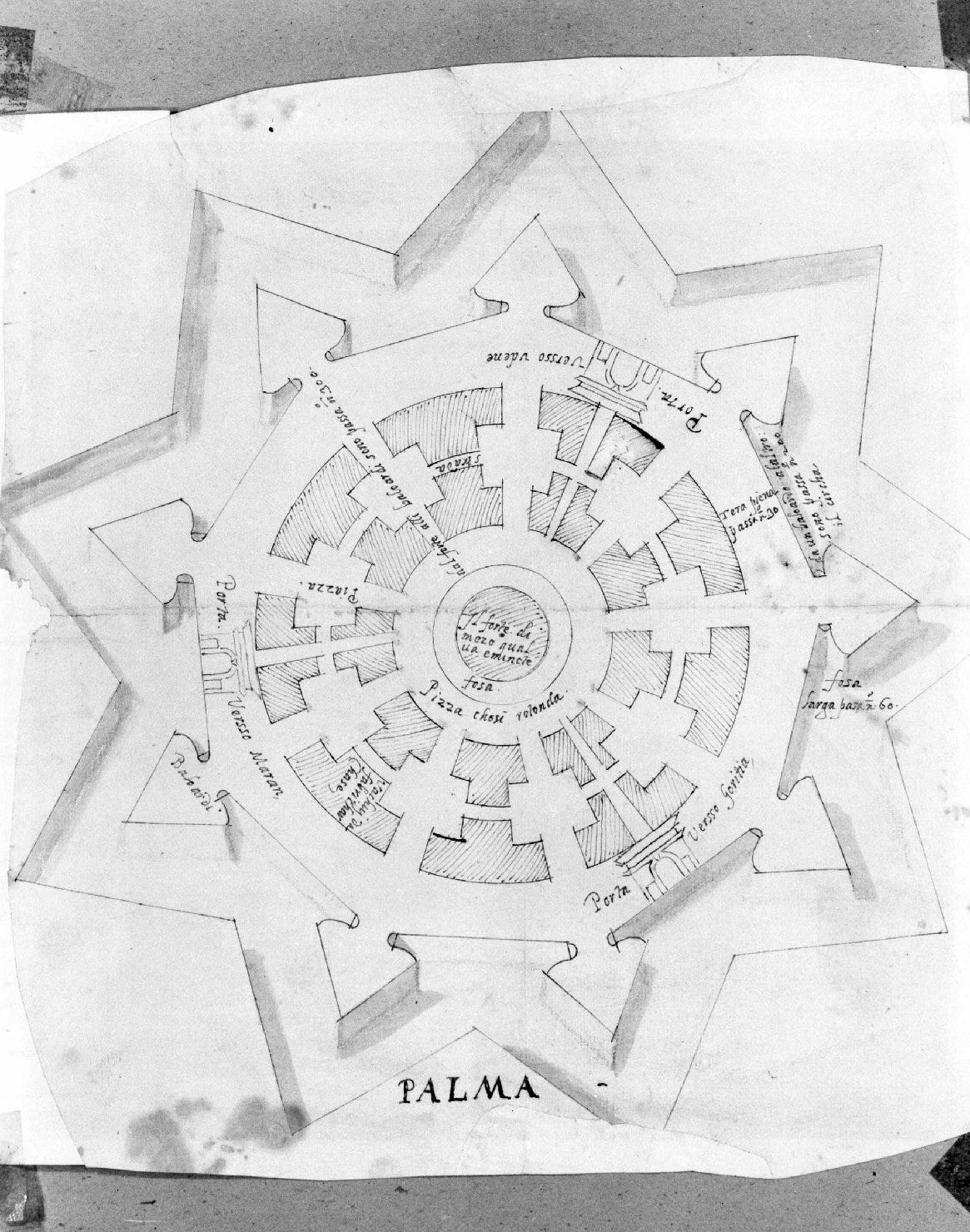

Set amid the Friulian plain, 20 km southeast of Udin, the fortress of Palmanova is immediately recognisable from the air: a nine‑pointed star whose bastioned tips project like rays from a central core.

Founded by the Republic of Venice in 1593 and listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2017, the settlement is considered the most complete example of late‑Renaissance military urbanism. The fortress embodies two intertwined ideas that defined the XVI century: the trace italienne, the new science of low, thick, angled ramparts designed for gunpowder warfare, and the humanist pursuit of the “ideal city,” whose geometric harmony was thought to encourage social harmony.

Understanding Palmanova, therefore, means reading it as both an instrument of war and an ideological manifesto: a defensive system engineered to arrest Ottoman and Habsburg expansionism, and a social experiment meant to embody a utopian ideal and Venetian technical ingenuity.

Historical Context and Foundation

During the XVI century, the Venetian Republic was squeezed between two aggressive forces. To the east, the Ottoman corsairs raided the Adriatic ports and threatened the lagoon itself; to the north‑east, the Habsburgs sought an overland corridor into the Po Valley. The loss of Gradisca in 1511 underscored the weakness of Venice’s eastern hinge and persuaded the Senate that a purpose‑built stronghold was indispensable.

Extensive surveys were carried out in 1593 by a board of five patrician inspectors. They selected a low rise where the Roman Via Julia Augusta intersected the medieval Strada Ungaresca - two arteries that could supply the fortress and, if necessary, funnel Venetian troops into imperial territory. The ground was sufficiently dry for earthworks yet close enough to the Natisone River to fill the defensive ditches.

The first stone was ceremonially laid on October 7th 1593 - the 22nd anniversary of the Holy League’s victory at Lepanto and the feast of Saint Justina, thereafter the town’s patron. The name “Palma” (palm frond) evoked triumph, while “nova” would be added by Napoleon two centuries later to mark a new political era.

Two local legends are attributed to the foundation of the fortress-city: the first is recounted by the priest‑historian Francesco Palladio degli Olivi. He recalled that, in 1573, a local herdsman named Camotio who dozed off under an oak exactly where the fortress now rises. In his sleep he watched crowds of labourers excavating ditches with strange machines and sewing ramparts into the soil. “What are you building?” he asked. “A fortress,” they replied, as if that were obvious. Mocked for years as a drunk visionary, Camotio finally laughed last on 7 October 1593 when Giulio Savorgnan laid the first stone on the very spot of his dream-vision.

The second legend tells that, while finalising the ground‑plan, five Venicean Provveditori were caught in a violent storm and ducked into a roadside chapel between Palma and San Lorenzo. A gust of wind unlatched a window, and a spiderweb drifted down onto the table like a ready‑made blueprint - the same radial lattice that would become Palmanova’s nine‑point star.

Designing the Fortress‑City

Chief engineer Giulio Savorgnan drew on his experience building bastioned fronts in Cyprus, Crete and Bergamo, while architect Vincenzo Scamozzi - a late pupil of Paładio - supplied the humanist urban vocabulary that would inspire the internal city planning.

Overall coordination rested with Senator Marcantonio Barbaro, head of the five Provveditori Generali (among them Jacopo and Zaccaria Contarini, Marino Grimani and Leonardo Donà) who secured funding, labour and supplies from the Venetian mainland. Technical calculations were further refined by Lombard engineer Marcantonio Martinengo di Villachiara, whose treatise on proportions guided the sizing of the nine bastions.

This multidisciplinary team blended cutting‑edge fortification science with renaissance theories on the ideal‑city, fulfilling the Senate’s dual mandate of military impregnability and civic order.

Palma’s key defensive elements were the following:

Bastions (Baluardi): Nine arrow‑headed bastions - named after Venetian nobles - form the tips of the star. Their orillons protected the flank guns while their flanks and faces allowed enfilading fire along the curtain walls.

Curtains (Cortine): Straight embankments joining the bastions; three host the monumental gates. Each curtain is revetted in stone and brick and fronted by a broad moat.

Cavaliers (Cavalieri): Two raised gun platforms crown every curtain, giving a total of eighteen elevated batteries that dominated the surrounding plain.

Ravelins (Rivellini): Nine free‑standing triangular outworks added in the 1660s beyond the wet moat, placed opposite each curtain to force besiegers to split their attack and to capture multiple obstacles before reaching the main wall, and to shield the gateways. Many incorporated false gates (Falsaporte)—decoys that led assault columns into lethal cul‑de‑sacs.

Moat (Fossa): Wet outside the first enceinte, dry in front of ravelins and Napoleonic lunettes; up to 80 m wide, it prevented mining and kept attacking artillery at distance.

Falsabraghe: Low counterscarp banks running parallel to each curtain at ditch level; they screened troop movements and masked the true line of defence.

Lunettes: Nine Napoleonic earthworks thrust a further 400 m into the countryside. Surrounded by a dry ditch and dotted with small redoubts, they provided advanced artillery positions and lengthened the siege perimeter.

Sortite or Poternas: Covered passages bored through the bastion mass allowed garrison sorties and safe transfer of guns and cavalry under concealment.

Camicia: A smooth stone “shirt” covering the inner walls of scarp and counterscarp, difficult to scale and crucial for holding the earthen core in place.

Caponieres and Traditori: Hidden flanking positions for musketry and grapeshot, sweeping the dry ditch around gates and outworks; they turned captured ground into deadly traps.

Fortified Barracks & Logge Fortificate: Casemate barracks of Napoleonic date and vaulted guardhouses embedded in each bastion; interior ramps link them to the sortie passages, so troops and artillery could exit quickly onto the glacis.

Three monumental gates: Porta Udine, Porta Cividale, Porta Aquileia pierce the enceinte, each fronted by a lunette that could be flooded in times of siege.

Inside the walls, six radial avenues converge on Piazza Grande, a perfect hexagon measuring 100 m across. The square hosted military parades and weekly markets, flanked by the Duomo (begun 1603) and the Provveditore’s Palace. Surrounding blocks follow a concentric street grid; plot sizes were deliberately uniform to reinforce the ideal of social equality.

Building Phases

Although conceived as a single organism, Palmanova evolved through three successive building campaigns, each reflecting new artillery technology and shifting political realities.

First Ring (1593–1623): in an age when gunpowder demanded broad, low and mighty earth ramparts, Venice delivered. Engineers shaped the first enceinte into nine arrow‑head bastions linked by straight cortine, creating an enneagon whose points could protect one another with interlocking fire. A sweeping wet moat wrapped the circuit, while three monumental gates - Udine, Cividale and Aquileia - punched through the curtains to control access. Raised over thirty years by Croatian and Friulian labourers, the walls were revetted in hewn limestone, topped with a 7‑m‑wide artillery platform and filled with powder magazines, barracks and storerooms.

Second Ring (1658–1690): by the mid XVII century, Venice judged the star still too close for comfort. A second belt of defence sprang up in the form of nine ravelins - stand‑alone, arrow‑shaped bastions planted beyond the moat along every straight curtain. The very first to be built watched over the three city gates, eternal soft spots in any fortress wall. Those outworks compelled an attacker to cross open ground, storm an island of guns, then face the original rampart still bristling behind. The upgrade included covered ways for hidden troop shifts, sky‑grazing cavaliers to lob counter‑battery fire and a lattice of caponniers beneath the earth. A freshly sculpted glacis finished the job, shielding the stone face from direct artillery hits.

Third Ring (1806–1813): when Napoleon seized the Venetian mainland in 1806, he tasked Colonel Gabriel Chabert with upgrading the fortress to meet the Grande Armée standards by adding nine detached lunettes - triangular earthen bastions set about 400 m beyond the ravelins and ringed by a dry ditch. Pushed deeper into the plain, each lunette kept enemy siege batteries at a distance, shielding Palmanova’s streets, magazines and barracks from direct fire. Linked by covered ways and fitted with traverses for flanking guns, the new belt perfected a flexible, multi‑layered “defence in depth” that embodied Napoleonic doctrine.

Together the three rings enclose an area of 1.3 km², while the outermost perimeter forms a 7‑km polygon integrating 9 bastions, 9 ravelins, 9 lunettes and 18 cavaliers.

This impressive arsenal of defensive architecture would deter any attacking army until the XIX century, when the fortress would be besieged in three different occasions (1809, 1814, 1848) - surviving both the Venetian Republic and the heyday of the early modern bastion, by then almost obsolete. Aside from these episodes, Palma would be captured through trickery in 1797, when an Austrian major managed to briefly occupy it before it fell under French authority.

Beyond the mathematics of defence, Palmanova doubles as a numerological masterpiece: its nine‑point star (3 × 3) is wrapped by three concentric walls and pierced by three monumental gates. Inside, eighteen radial streets - of which six are main arteries - spiral toward Piazza Grande, a near‑perfect hexagon whose 360‑degree symmetry can momentarily disorient visitors gazing at identical façades on every side.

Population Challenges: From Ideal City to Garrison Town

The Venetian Senate expected Palmanova to house 3 000 civilians who would provision the garrison and model Venetian civility. Incentives included ten years of tax exemption, interest‑free loans, and free house timber floated down the Tagliamento. When voluntary migrants proved scarce, an extraordinary decree of 1622 offered land to pardoned criminals and deserters.

Several factors inhibited population growth:

The plain’s malaria‑prone marshes deterred the settlement of families.

Strict building codes and military curfews cramped commercial freedom.

Regional trade favoured established hubs such as Udin and Cividât, limiting Palmanova’s market reach.

By 1700, the civilian count hovered around 1200—barely a third of projections—while the military garrison averaged 2000. Urban life revolved around drills, supply convoys and the modest needs of quartermasters and sutlers rather than artisanal guilds.

Other planned towns of the period reveal similar patterns: Sabbioneta (Lombardy) thrived only while its founder Vespasiano Gonzaga financed its courtly splendour, and Neuf‑Brisach (Alsace) struggled once French troops redeployed after 1815.

Palmanova’s demographic plateau illustrates a broader limit of Renaissance idealism when confronted by early‑modern socioeconomic reality.

Palmanova After Venice

After the fall of Venice, Palmanova would survive as a fortress, as during the Austrian and later italian occupation it served as a regional logistical hub, especially during World War I, as the front stabilized on the Isonzo River.

Declared a National Monument in 1960, Palmanova now hosts about 5400 residents and welcomes many more tourists, scholars and military buffs each year for the following attractions:

Bastion Walk: A continuous 7‑km cycling and hiking loop atop the ramparts, with interpretive panels explaining firing angles, powder magazines and shot‑furnaces.

Military History Museum: Housed inside Porta Cividale, its exhibits include XVII-century siege diagrams, Napoleonic uniforms and a reconstructed trench periscope.

Palma alle Armi: Each second weekend of September, 600 reenactors in Venetian, Austrian and French uniforms stage skirmishes, artillery drills and candle‑lit bivouacs.

Subterranean Tours – Guided walks through the caponniers and counter‑mine galleries, some stretching 200 meters beneath the glacis.

Piazza Grande – Lined with cafés, the cathedral and a rare example of an early Baroque loggia (converted into a cinema during the Fascist period).