At a cursory glance at the historical record, the etnonym Veneti may appear to the reader as an aberration, a blimp in the history of some obscure people that inhabited Europe in ancient times and came to us only as a footnote of a bigger story.

It is, however, peculiar how persistent it is and how unadulterated the name is across Europe - and beyond, as we shall see in this article.

The ancient Veneti have long captivated historians, archaeologists, and linguists due to their mysterious presence across Europe from the Adriatic to the Baltic. References to the Veneti abound in classical literature, such as Homer's Iliad, and the works of ancient historians like Tacitus and Pliny, as well as Caesar’s De Bello Gallico. These portray the Veneti as significant players in ancient Europe's geopolitical landscape, often engaging in alliances or conflicts with other prominent civilizations.

The Armorican Veneti, situated in modern-day Brittany, were known for their maritime prowess and influential trading relations, before being annihilated by Caesar’s armies during his conquest of Gaul.

The Vistula Veneti occupied territories in Central Europe, giving their name to a myriad peoples around them (Wends, Venedi, Vandals, etc…)

The Anatolian Enetoi, according to Homer's Iliad, played a role in the Trojan War and were considered the mythical ancestors of the Adriatic Veneti.

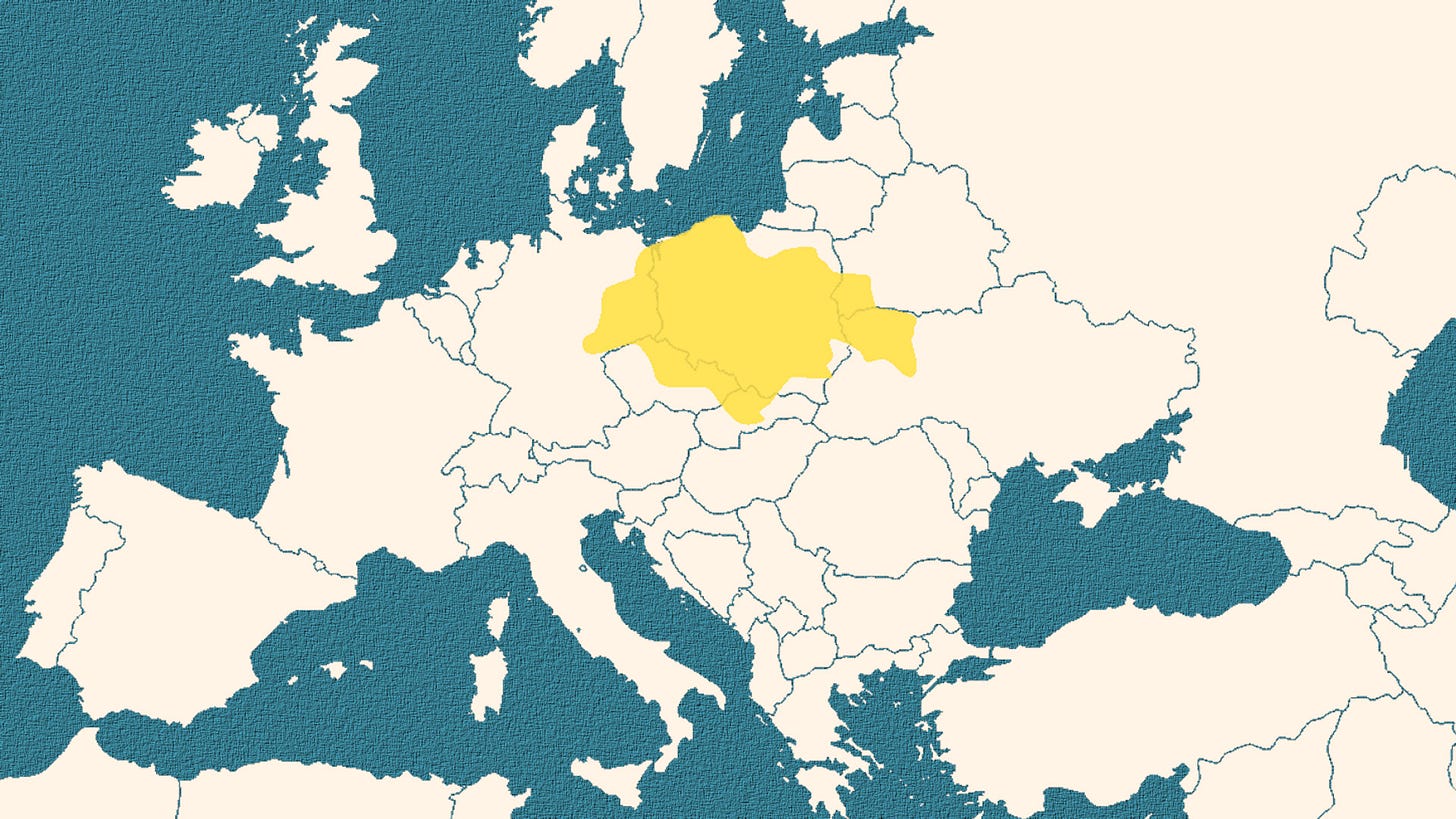

Despite their prominence, the origins and migration patterns of the Veneti have remained debated and speculative. Recent research challenges traditional narratives - who see the Veneti as either Celtic, Germanic or Slavic - proposing the idea of a Central European homeland for the Veneti, and of a shared ancestry among the populations that bear this name, ascribing its origin to either the Urnfield Culture (1300-750 BC) and the related Lusatian Culture (1200-500 BC).

Both cultures practiced cremation, a funerary practice that is echoed in the Este culture of the upper Adriatic, suggesting a migratory pattern - as part of the Indoeuropean migrations - already supported by archaeologic and genetic evidence.

It is crucial, at this point, to understand the chronology of the development of the various material cultures of Central Europe, and to distinguish the Este Culture from the Hallstatt Culture, which emerged chronologically later and exhibited notable differences, particularly in funerary practices. While the Este Culture maintained the tradition of cremation and urn burial, the Hallstatt Culture favored inhumation, marking a significant departure in burial customs.

Although the later impact of the Hallstatt Culture on regions like Polish Slesia and Veneto is undeniable, the Hallstatt Culture’s development is chronologically posterior to the Este Culture, thus rendering it less relevant to the topic of the origins of the Veneti.

If we analyze the phenomenon of the Urnfield Culture, a Late Bronze Age civilization that later gave rise to the Este Culture (typical of the ancient Adriatic Veneti), the importance of the "religious" factor in the spread of this new cult centered on the cremation of the dead becomes clear. Simultaneously, the symbolic messages of the new religion were spreading, particularly the emblem of the Solar Boat – a solar circle above the semicircle of the boat – is repeated in all shapes and variants in the Venetian material culture.

How did the mysterious symbolism of this culture, which emerged in Central Europe on the border between present-day Poland and Germany, arrive in the Veneto region? Beyond the boundaries assigned to its original nucleus, namely the Lusatian Culture, there are some traces of this civilization in Austria – south of the Danube – thus sufficiently close to Veneto.

The spread of the Urnfield Culture in Veneto, properly understood as a "cultural" fact, is therefore obvious and evident. It remains to be proven whether the transmission of the cultural phenomenon was accompanied by an actual migration of people or not. The idea of a population movement is the most probable hypothesis, if only because the period around 1200 BCE was characterized by a disruption of the settlement patterns of numerous European peoples, a chain reaction of explosive power that spread in waves from Central-Eastern Europe towards the south and west, with its domino effect having its epicenter in the Baltic area, where the original nucleus known as the Lusatian Culture had manifested itself. It's likely that the introduction of the horse for military purposes (advancing beyond the bronze-age chariot), could have - at least in part - caused the migrations of the period, along with climate change.

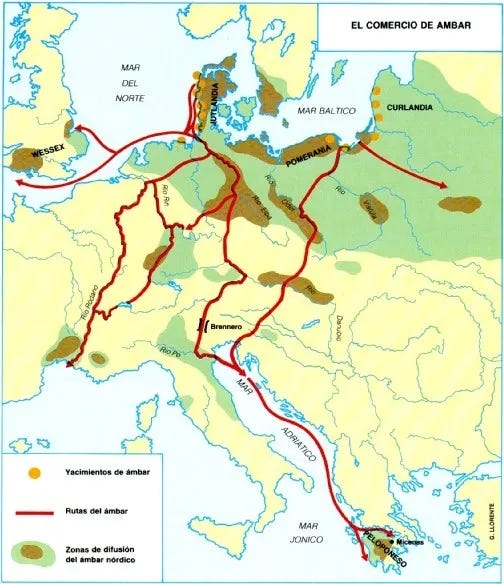

Genetic evidence suggests a migration of the progenitors of the Veneti took place not only to the Upper Adriatic but also to other areas like Brittany and the Pontic area, and beyond. It’s not a coincidence that those areas were inhabited by people that retained the Venetian etnonym.

It is thus easy to imagine how the disparate Venetic peoples of Europe could be so geographically separate but also so connected: genetically, culturally, and religiously, as descendants of an older culture located around modern-day Poland.

These connections are reflected in the commerce of that era of Venetic expansion, as the Veneti - wherever they settled - were apt traders and navigators, often managing the commerce between distant lands.

One missing piece of the puzzle in this hypothesis is the classical Venetian founding myth, which links the origins of the Venetian people to the events of the Trojan War in Homer's Iliad. According to the myth, Antenor, counselor to King Priam of Troy, fled the city's destruction and led his people, the Enetoi, to the upper Adriatic, where they eventually founded the city of Padua. Additionally, further evidence comes from Homer's mention of the Veneti as allies of the Trojans, apparently contrasting with Tacitus and Pliny attributing a northern location to the Veneti, who are said to live near the Finns.

How can these seemingly contradicting accounts be reconciled - both among each other and with the archaeology discussed above, which points to a southward migration from Central Europe? Let’s find out.

Felice Vinci’s Baltic Hypothesis

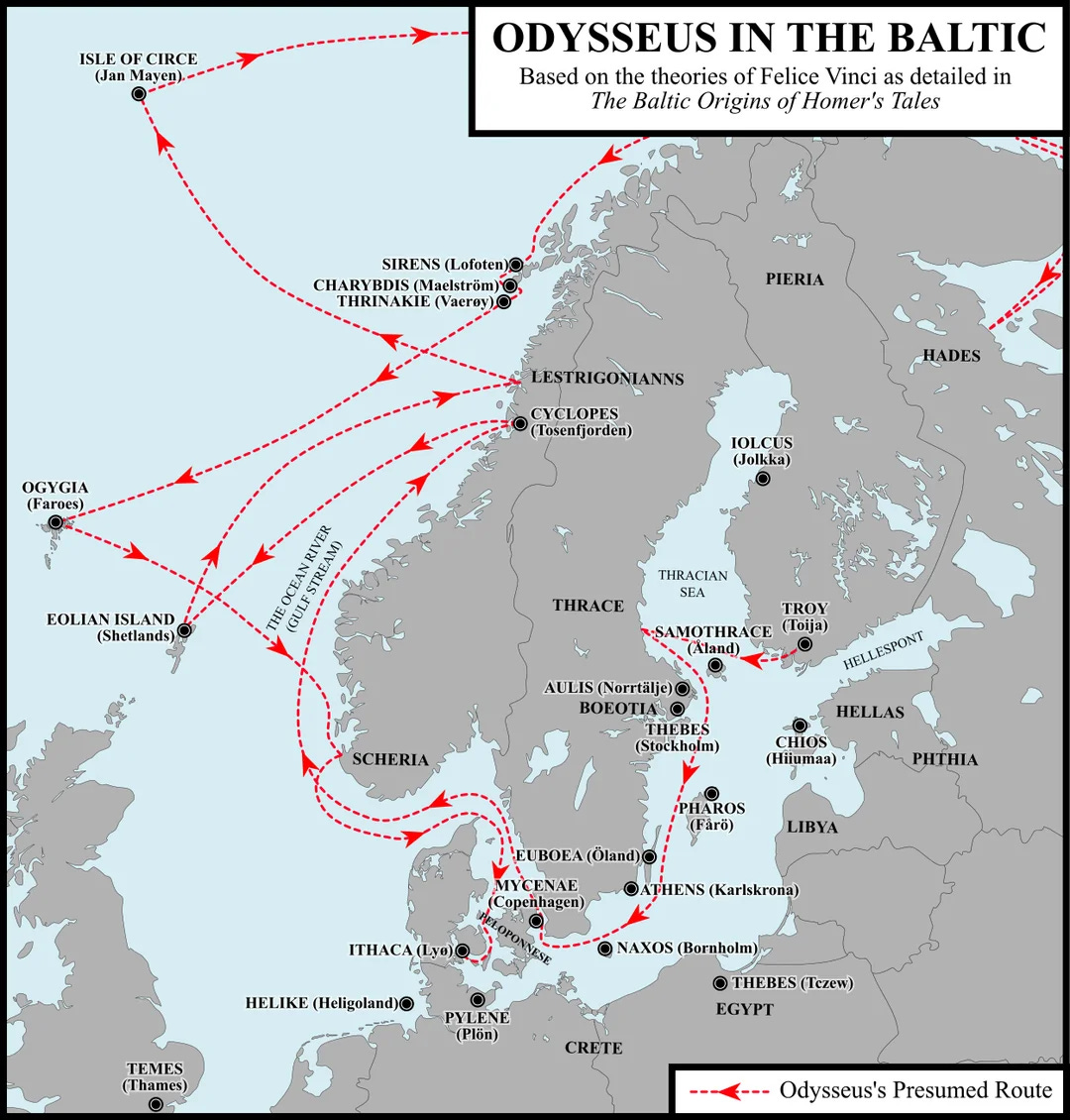

The Baltic Hypothesis, proposed by Italian scholar Felice Vinci, presents a provocative reevaluation of the geographical and historical settings of Homer's epic poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey, suggesting that these events took place not in the Mediterranean world, but in the northern regions of Europe, particularly around the Baltic Sea.

Vinci's hypothesis draws on several key points:

Geographical Descriptions: Vinci argues that many of the geographic features described in Homer's works, such as rivers, islands, and landscapes, more closely resemble those found in northern Europe rather than the Mediterranean. He points to specific details, such as the long daylight hours in summer and the presence of fir trees, which are more characteristic of northern latitudes.

Climate and Seasonal Cycles: Vinci contends that the climate and seasonal cycles described in the epics, including long winters and short summers, align more closely with the northern European climate than with that of the Mediterranean. He suggests that the harsh winters and icy seas mentioned in the Odyssey, for example, better fit the Baltic region than the Mediterranean.

Cultural and Linguistic Parallels: Vinci identifies linguistic and cultural parallels between the peoples described in Homer's works and historical populations of northern Europe. He points to similarities in names, customs, and traditions, as well as archaeological evidence suggesting connections between the Bronze Age cultures of the Baltic region and those of the Aegean. For example, the funerary practices in the Iliad closely resemble those of the Urnfield Culture rather than those of the Myceneans of the same period.

Astronomical References: Vinci also explores astronomical references in the epics, such as descriptions of the night sky and celestial events, to support his hypothesis. He suggests that these references may align more accurately with the northern European sky than with the Mediterranean.

Expanding on Vinci’s research, venetian author Diego Marin proposed a similar hypothesis in his recent book “Platone nel Baltico - i Veneti di Atlantide”. While some of his assertions require a more critical analysis, they nonetheless provide a coherent hypothesis that elegantly ties together many conclusions of recent studies, who point to the existence of a relatively advanced civilization in Northern Europe in antiquity.

The full book can’t be related here, but we’ll provide a brief summary.

An ancient civilization existed before the end of the last ice age - in accordance with the hypotheses of Graham Hancock.

Based on the geography proposed by Vinci, the location of Atlantis is identified with Jutland, with its domains stretching from southern Scandinavia to the river Vistula (named Aegypt). Its existence is dated from 5000 BC to 2000 BC.

The continental domain of Atlantis was inhabited by the Veneti, alternatively named Cureti in other periods, who initially lived in Atlantis, then Troy (southern Finland) and Courland (modern-day Latvia), and then Pomerania, before migrating southward around the middle of the II millennium BC.

The northern Atlantic was a place of trade and contacts in antiquity, with Atlantis itself being derived from a civilization further north.

It is also interesting to note that this chronology fits with the one found in the Oera Linda Book, who posits the end of Altland to 2193 BC after a cataclysm. But this is another story, and we’ve just scratched the surface here.