The destruction of the village of Longarone and the subsequent massacre of its inhabitants by an immense mass of water overflowing from the dam above it on the evening of 9 October 1963, known as the ‘Vajont Disaster’, undoubtedly represents the greatest environmental and engineering disaster in the recent history of Veneto.

That evening, more than 1,900 people lost their lives, swept away by the water, stripped bare and literally torn to pieces by its fury, buried alive under mud and rubble, their bodies dragged for kilometres along the course of the River Piave together with the carcasses of livestock. Vegetation and buildings were razed to the ground, and railway tracks were twisted as if they were made of cardboard.

Given its peculiarity, or rather uniqueness, this tragedy often arouses great interest in those who hear about it for the first time. At the time of the events, the news shook the world of dam builders and marked a real watershed in the field, to such an extent that the ICOLD (International Commission on Large Dams) updated its guidelines to favour more cautious and less optimistic construction approaches, which at the time was a real paradigm shift.

But how did this come about? What was the sequence of events that ultimately led to such a catastrophe?

Historical context

During the post-war period, the growing demand for electricity due to the rapid industrial development of Italy prompted the large electricity companies, then private companies, to identify new sites suitable for the construction of various types of power plants. In this context, SADE. (Società Adriatica Di Elettricità), a large Venetian company, began designing a majestic hydroelectric plant in the Vajont valley, a pre-Alpine valley located in a deep gorge between Mount Toc and Mount Salta, in the municipality of Erto-Casso in the province of Pordenone, through which the stream of the same name flows, confluing with the Piave river.

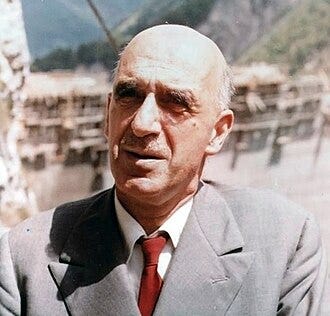

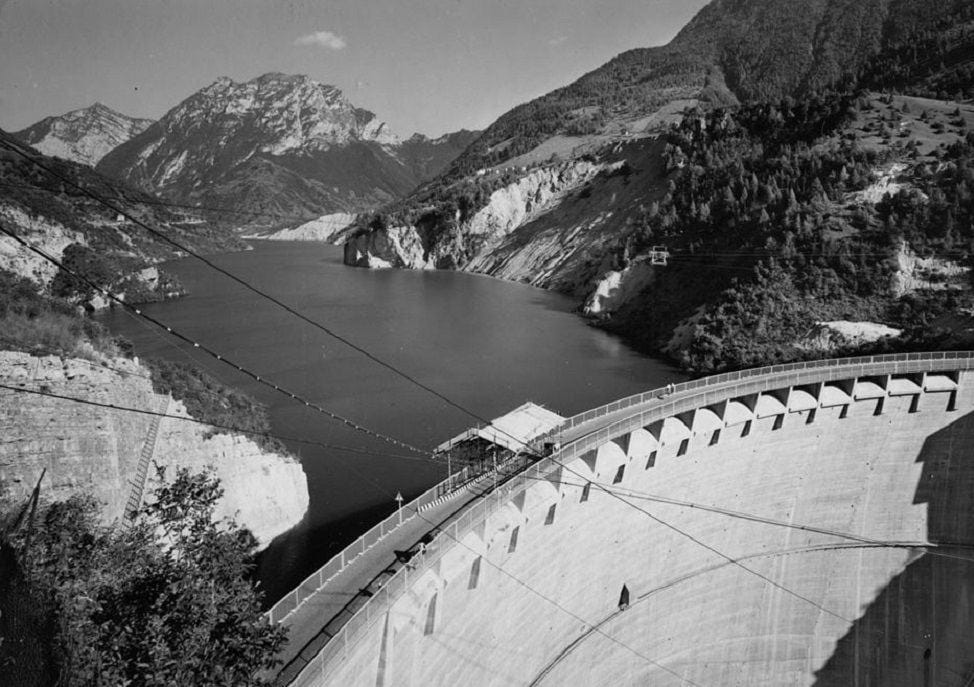

The potential of the valley for this purpose had already been identified decades earlier by the Venetian company, which entrusted its leading engineer Carlo Semenza, one of the world’s most experienced dam designers of the time, with the design of the dam that would block the valley, a so-called ‘double arch dam’ , which used an arched geometric shape both in height and width, exploiting the laws of physics rather than the simple mass of concrete to withstand the pressure of the water.

The exceptional depth of the valley and its geographical location made it a perfect site for a water reservoir. The main function of the plant was not to produce electricity, but rather to act as a large reservoir where water used by other SADE hydroelectric plants located at higher altitudes could flow, so as to guarantee a large water reserve, a large supply of water that could be used in periods when the flow of the rivers was lower, in order to produce electricity continuously throughout the year. The reservoir had a capacity of 168 million cubic metres of water, which is more than double the combined capacity of all the reservoirs in the SADE Alpine network that flow into the Vajont.

In 1948, the purchase began, at a reduced price, it must be said, of the land owned by the municipality and the inhabitants of Erto and Casso, which would have been the site of the dam and the banks of the future artificial lake. The actual construction of the dam began in August 1958. the initial project established a height of 200 metres for the structure, but the project was subsequently modified during construction to reach a height of 260 metres, making it the tallest dam of its kind in the world at the time, in order to make better use of the valley’s capacity and reach the aforementioned flow rate of 168 million cubic metres of water at maximum reservoir level.

Signs of geological instability

In the spring of 1959, the first doubts arose about the geological stability of the area surrounding the dam and the banks of the artificial lake. The event that prompted Carlo Semenza to commission further checks in this regard was the Pontesei landslide on 22 March 1959, where a hydroelectric plant owned by SADE itself, located in Forno di Zoldo, 8 km away from Vajont as the crow flies, a mass of rocky debris from one of its banks collapsed into the artificial lake, generating a wave that caused one fatality.

Following this event, Leopold Mueller, a mining engineer specialising in geomechanics and professor at the University of Salzburg, who had already carried out geological surveys in previous years concerning the stability of the dam’s foundation area, was commissioned to carry out new surveys to identify any instability in the lake’s banks.

A similar task was also entrusted to the young geologist Edoardo Semenza, son of engineer Carlo Semenza, the dam’s designer.

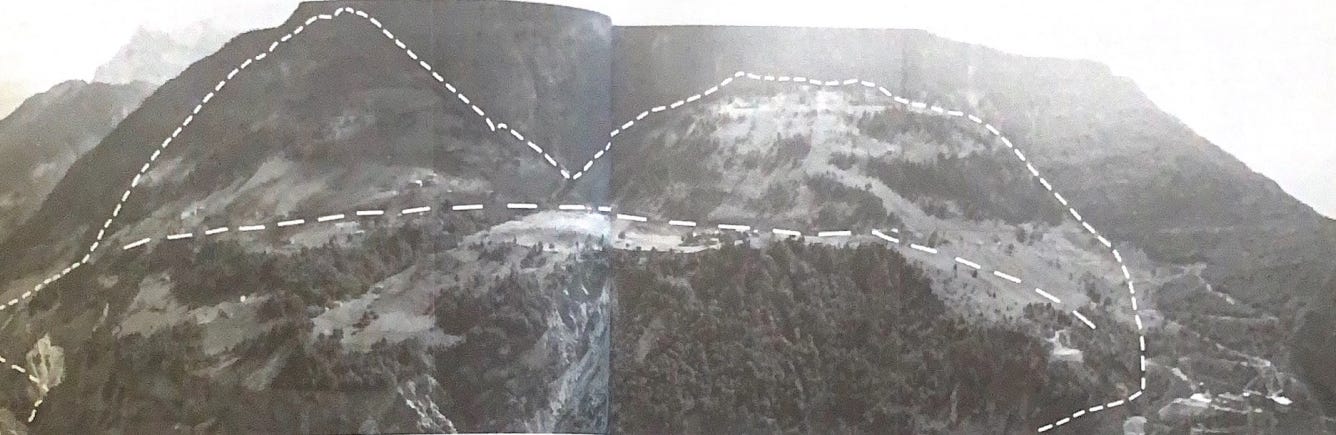

Following his inspections, at the end of August 1959, E. Semenza presented a report in which he declared the presence of an ancient landslide (or palaeofrana) initially estimated at around 50 million cubic metres on the side of the valley opposite the villages of Erto and Casso, on Mount Toc. In the same report, the hypothesis was formulated for the first time that this landslide could move following the filling of the lake.

He gave the report to his father Carlo, who, given the sensitivity of its content, asked him to have it reviewed by geologist Giorgio Dal Piaz, a leading national expert on the subject and the person who carried out the first inspections and geological surveys of the valley, as well as E. Semenza’s professor during his studies at the University of Ferrara, with the aim of having it examined. However, Dal Piaz rejected Semenza’s thesis, downplaying the extent of the landslide that had been discovered.

In February 1960, with the construction of the dam still in progress (it would only be completed in September of the same year), the first water filling tests were started inside the valley. In May, when the filling level reached 600 metres above sea level (above sea level), the first signs of instability began to appear on the left bank of the lake, where E. Semenza had identified the landslide the year before. In October, a large continuous crack began to appear on Mount Toc, roughly M-shaped, about 2 km long and located several hundred metres further upstream than what had initially been hypothesised as the ends of the landslide mass.

These signs of instability reached their peak on 4 November 1960 when, with the reservoir at an altitude of approximately 650 metres above sea level, a mass of rock measuring 700,000 cubic metres broke away from Mount Toc, sliding into the lake below and generating a wave several metres high, which caused no damage.

This was clearly only a tiny part of the enormous mass of landslide actually present in the area, but it was the event that convinced SADE to take the first concrete steps to try to control the dangerous situation that was developing.

Mueller’s opinion was sought and, unlike Giorgio Dal Piaz, he confirmed (following his inspection) the hypothesis formulated by E. Semenza the previous year regarding the presence of a ‘large landslide’.

Mueller recommended a gradual lowering of the reservoir level in order to try to stop or at least slow down the movement of the landslide, since it was precisely the increasing pressure exerted by the water on the banks of the lake, due to the rise in the reservoir level in previous months, that triggered the movement of the landslide. The water penetrated through the permeable soil, reaching an underlying layer of fractured rock, which, when wet, caused the ground to become unstable.

This approach proved effective, with the movement of the ‘great landslide’ slowing down to a near standstill as the level dropped to 600 metres above sea level, but the ultimate goal remained to reach the maximum reservoir level of 722 metres above sea level sooner or later in order to obtain official approval for the facility.

Before proceeding with the new reservoirs, C. Semenza took advantage of the lowering of the lake level to build a ‘bypass’ tunnel, an underground tunnel he designed, dug on the side of the valley opposite the ‘great landslide’, which would allow, according to the physical principle of communicating vessels, the use of the water in the reservoir even after a possible collapse of the landslide, if the latter had divided the large lake in half, forming two smaller ones. In this way, all the water remaining in the lake cut off by the dam could still flow into the one behind it.

At the same time, he commissioned the Institute of Hydraulics at the University of Padua, directed by Professor Augusto Ghetti, to construct a 1:200 scale physical-hydraulic model of the artificial lake area in order to conduct experiments simulating the effects of the collapse of the ‘great landslide’ on the plant and the adjacent villages. The experiments took place from August 1961 to April 1962 and consisted of dropping a mass of gravel bags, which were supposed to simulate the mass of the ‘great landslide’, into a scale model of the artificial lake, and then measuring the height of the wave that was generated and its effects on the surrounding environment.

These experiments showed that a reservoir level of 700 metres above sea level was absolutely safe, within which even the most catastrophic scenario would not have been able to produce effects that would have affected the adjacent villages. However, the experts themselves recognised the partial reliability of these results, given the impossibility of using a material that could reproduce the true density of the landslide mass and the friction and inclination of its sliding plane (i.e. the speed of fall).

In October 1962, the filling of the reservoirs resumed, reaching a height of 700 metres above sea level in November, but was interrupted again due to a resumption of movement, measured by detection systems that SADE technicians had installed along the fissure that had formed along the ‘upstream’ boundary of the landslide in previous years to monitor its movement. It was therefore decided to lower the level of the reservoir once again as a precautionary measure, this time to 650 m above sea level. This decision was taken under the direction of Alberico Biadene, who took over from C. Semenza after his sudden death on 30 October 1962 as central director of SADE’s hydraulic construction service.

The Nationalisation of the plant

Meanwhile, in 1963, the Venetian company began the process of integration into ENEL, following the approval in December 1962 of the law on the nationalisation of electricity companies, a law promoted by the centre-left Italian government led by Amintore Fanfani.

The effect of this decision are not to be underestimated: Alberico Biadene - who took over from Carlo Semenza after his death - found himself lacking anyone to consult on the decisions to be taken, and wouldn’t receive any feedback in terms of operative decisions from the new state administration - despite continuous reports on the situation. He was alone, facing an imminent crisis, quickly taking the measures he deemed necessary.

The third (and final) filling began in April 1963, and the lake level rose slowly until it reached 700 metres above sea level in July of the same year. At that altitude, as on the previous occasion, the landslide movements resumed, albeit to a lesser extent, but this time, instead of starting the release again, the decision was taken to continue raising the lake level with the aim of reaching an altitude of 715 metres above sea level.

Towards the middle of September, when the lake was at an altitude of 710 m above sea level, the movement of the landslide mass began to accelerate, and it was at this point that what would prove to be the point of no return in this story was reached. At the end of the month, a rapid release of water was initiated to return to the safety level calculated by Ghetti at 700 m above sea level, but this time, instead of stopping, the movements increased exponentially (the day before the disaster, they were as much as 30 cm per day).

It was now accepted by experts that the collapse of the landslide was imminent, but, confident in Ghetti’s indication of the safe reservoir level, they tended to underestimate the possible side effects of a wave caused by the ‘great landslide’ entering the lake.

In fact, even in the most pessimistic scenarios, it was believed that if the safety level was respected, the wave would not overflow more than ten metres beyond the edge of the dam. The only measure taken in this regard was to evacuate all the houses and hamlets of the villages located close to the shores of the lake below an altitude of 730 metres above sea level, and, of course, to evacuate all the houses located more generally on the left side of the valley, the side occupied by the landslide, i.e. the side opposite the villages of Erto and Casso.

The most widespread concern was actually that the dam would not withstand such pressure, and the last countermeasure taken was to further reinforce the dam’s anchor points to the rock by installing additional tie rods.

October 9th, 1963

On 9 October 1963, given the dramatic increase in the movement of the landslide, it was now clear to the engineers that the collapse would occur that same day. In the evening, the Carabinieri barracks were alerted in order to block all access routes to the valley. At the dam’s command station, teams of technicians and engineers monitored the situation visually using electric lights and saw with their own eyes the scrub on the landslide mass bending downwards towards the lake.

At 10.39 p.m., the ‘great landslide’ collapsed. In 20 seconds, what turned out to be 270 million cubic metres of rock descended towards the lake, which was located at an altitude of 700 metres above sea level.

Twenty seconds instead of the 60 used as a benchmark (already considered an exceptionally short time) during Ghetti’s tests to simulate the most catastrophic of possible events.

It should be noted that, as the experts later observed in court during the trials, ‘since kinetic energy is proportional to the square of the speed, with a fall time of one third, i.e. 20 seconds instead of 60, corresponding to a triple speed, the effect would have been nine times greater’, i.e. a wave 180 metres high instead of the 30 metres measured during the tests, which would broadly correspond to reality. In fact, the wave generated would overflow more than 200 metres beyond the edge of the dam, sweeping over the villages of Erto and Casso, leaving them almost unscathed, with the exception of a few hamlets or isolated houses.

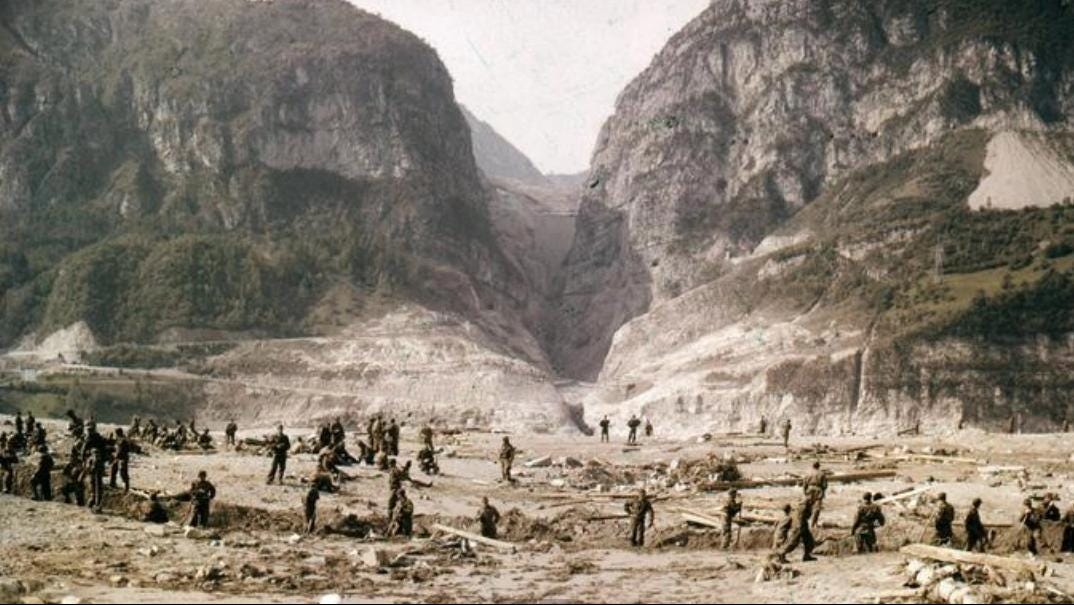

The inhabitants of the village of Longarone, located practically at the foot of the dam, just outside the gorge, alerted by the enormous roar produced by the collapse of the landslide, saw a wave of 50 million cubic metres of water crash down on them, immediately razing the village to the ground, before flowing into the Piave river, where the flood, heading towards the sea, caused damage as far as the hamlets of Belluno, carrying with it corpses and debris.

Despite this, the dam remained standing, after undergoing pressure 10 times greater than the maximum expected during the design phase. The only damage to the structure was the destruction of the power station and the control station, where numerous ENEL workers, technicians and engineers perished. The final death toll was over 1,900 people.

After the catastrophe

Following the catastrophe, the Italian Parliament set up commissions of inquiry with the aim of investigating the causes, responsibilities and circumstances that led to the disaster.

In parallel with the work of the parliamentary commissions, the judiciary launched its own investigations in the days following the disaster, based on complaints and evidence gathered, to ascertain any criminal liability. The actual trial began only in 1968 and concluded after three levels of judgment in 1971. Alberico Biadene was sentenced to five years in prison, while Francesco Sensidoni, inspector general of the Italian Civil Engineering Corps, was sentenced to three. Both were sentenced for the crime of ‘flooding, aggravated by predictability, including landslides and homicides’ for failing to give timely warning or order the evacuation of the affected towns. These sentences were considered excessively short by public opinion.

Tina Merlin’s narrative of the event

In 1983, the famous book ‘Sulla pelle viva’ (On Living Skin) was published, written by Tina Merlin. The book proposed an investigation, a reconstruction of the facts surrounding the Vajont affair, both before and after the landslide, which, as we shall see, would represent the most widespread narrative on the subject in the following decades. It was written by the author based on her experience as an investigative journalist throughout the affair.

In fact, Tina Merlin, a journalist for the daily newspaper L’Unità (the main mouthpiece of the Italian Communist Party at the time), with a past as a partisan courier during the German occupation of Northern Italy in the Second World War, had been closely following the events since 1959, publishing articles about the complaints and concerns of the inhabitants of the villages of Erto and Casso.

In the book, the facts were narrated mainly on the basis of assumptions, which was not necessarily done in bad faith, but also because of the author’s inability, like any other person outside SADE, to access reliable information about what was really happening in the valley.

Merlin wrote her book based on the accounts of the valley’s inhabitants and on minority reports produced by members of the Italian Communist Party (PCI) who were part of the parliamentary commission of inquiry and were probably driven by the same ideological dogmas as the author herself - aiming to cast the private company SADE in a bad light. These reports were rejected almost in their entirety by the judicial authorities as lacking logical foundation and being based on assumptions.

Basically, the narrative that emerges from the book is that of a SADE led by unscrupulous men who, in pursuit of pure economic profit, were willing to ignore scientific evidence, conceal the dangers from the public and jeopardise the safety of an entire community and the natural balance of a pre-Alpine valley, ultimately causing what is bluntly referred to as “a massacre”.

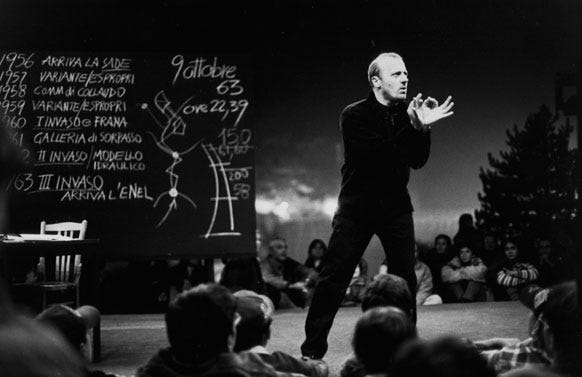

In 1997, actor Marco Paolini rekindled interest in the Vajont affair, which had gradually waned in previous years, through a television show, the script for which was based on Tina Merlin’s book and shared its militant content, albeit in a more balanced way. A speech, a fictionalised account of the story designed to capture the viewer’s attention, objectively enjoyable and artistically successful.

The programme was a great success in Italy at a national level and is still easily available on the web in its unabridged version. It is safe to say that it was this programme that created what is now the universally (or almost universally) accepted narrative of the story, and therefore mistakenly considered to be absolutely true. The programme even inspired the production of a film directed by Renzo Martinelli called ‘Vajont’.

Edoardo Semenza’s perspective

It is in this context that Edoardo Semenza, the geologist who first discovered the landslide in 1959 and son of engineer Carlo Semenza (the dam’s designer), driven by the desire to preserve the memory of his late father and all those who played a role in the events leading up to the disaster, decided to write a book to debunk a whole series of myths, assumptions and imaginative reconstructions that were part of the fallacious narrative of the Vajont catastrophe that spread over the years, drawing on his memories of that period as someone involved in the work to reconstruct a story of that disaster that was as close to reality as possible.

According to Edoardo Semenza, Merlin’s book and, by extension, Paolini’s show, were a deliberate attempt to misrepresent reality.

The book was called ‘La storia del Vajont - raccontata dal geologo che ha scoperto la frana’ (The story of Vajont - told by the geologist who discovered the landslide). In the first part of the book, the author provides a chronicle of the events from the point of view of those involved in the work, supported by technical analyses in the physical and geological fields, presented in the least difficult way possible for a ‘lay’ audience. In the second part, however, he devotes himself to dismantling, in an extremely precise manner, perhaps falling into nit-picking in some cases, the various inaccuracies that are part of the ‘official’ theory (that of Merlin-Paolini).

The book did not have a following comparable to that of ‘Sulla pelle viva’ (On Living Skin), in fact, it was never reprinted, partly due to the author’s death a few months after the book’s publication, and today it is difficult to find, both in physical and digital format, which is absurd given the interest that the Vajont story still arouses in public debate on the various anniversaries of the event, considering that we are talking about the point of view of one of the protagonists in the story of that catastrophe.

E. Semenza’s analysis of the Vajont disaster’s historiography

Below is a list of the most significant discrepancies that Edoardo Semenza identifies in his book between the ‘official’ version of the Vajont disaster and what he believes to be the reality of the facts.

Inadequacy of preliminary geological studies:

In hindsight, it has been claimed that it would have been appropriate to carry out in-depth geological studies on the stability of the slopes prior to the design of the dam, which would ideally be correct. The truth is that SADE carried out all the geological studies required by law at the time, even after the approval of the modification to the project during construction. These studies mainly concerned the stability of the dam’s foundation area and, more generally, the hydraulic integrity of the lake’s banks, and were carried out by Giorgio Dal Piaz. In fact, it was precisely the experience gained from the Vajont incident that led to the protocols in this regard being modified, making more in-depth studies necessary.

During these studies, the presence of landslide masses in the valley emerged, which were judged to be harmless, as they would later prove to be, such as the Pineda landslide near the village of Erto, or some small unstable rock masses in the Pian del Toc area, which, although they were part of the large mass that collapsed in 1963, at the time could not have raised any suspicion of what would turn out to be the ‘great landslide’ and did not constitute a danger on their own. The Italian State’s Higher Council of Public Works also requested, and SADE subsequently carried out, an assessment of the stability of the area around the village of Erto, which did not reveal any critical issues.

It should be noted that all this was forwarded to the supervisory bodies and deemed exhaustive and worthy of approval, as will be ascertained during the court proceedings.

Mueller’s diagnosis:

Merlin’s text first of all spreads the false information that it was the geomechanical engineer Leopold Mueller who discovered the ‘great landslide’ in 1959, and that E. Semenza was only hired later by SADE to provide further approval of the diagnosis, which would be logically absurd, to think that a young geologist who had graduated only a few years earlier could in any way legitimise or delegitimise the analyses of a university professor, as well as a pioneer in his field and a world-renowned luminary with decades of experience in the field. In reality, the opposite is true. As we have recounted in the summary of events in this article, it was E. Semenza who discovered the landslide and Mueller was then asked to analyse the report he had written.

In addition, the PCI parliamentarians on the commission of inquiry attributed to Mueller, in their reports, statements according to which, following the report he produced on the landslide discovered by E. Semenza in 1959, he advised SADE to abandon the project because ‘once the landslide had started moving, it would not stop completely any time soon’.

This is obviously false, not least because, following this same logic, the landslide would not have stopped even if the project had been abandoned. In reality, Mueller did state that the landslide would not return to a complete halt in the short term, but he also prescribed a series of measures to SADE to control the movement of the landslide and its danger as much as possible while awaiting new studies of various kinds on its composition. These measures included, for example, the slow and gradual lowering of the reservoir level, which proved effective in slowing it down, until the new reservoirs were clearly ready. He did not recommend abandoning the project at all.

On the basis of what has just been refuted, the ‘official’ theory therefore presents a narrative of SADE downplaying Mueller’s ‘inconvenient’ report for financial gain, so as not to lose the billions of lire invested in the construction of the plant by abandoning it.

Theory of the rush to testing:

According to the theory of the so-called ‘rush to testing’, which was originally formulated by Public Prosecutor Arcangelo Mandarino during the criminal trial and taken up by Merlin in her book, SADE would have pushed its managers to ‘force the pace’, regardless of the effects this would have had on the progress of the ‘great landslide’, in order to obtain the plant’s testing, which would only have taken place once the reservoir had reached and maintained a level of 722 metres above sea level. All this was done on the grounds that a tested plant would mean greater compensation for the company from the Italian state in the context of the nationalisation of electricity companies, which was announced suddenly in the spring of 1962 following a reversal of political alliances in the government that brought the socialists into the parliamentary majority.

This was the hypothesis that the author put forward in her book when she had to explain why SADE continued to raise the reservoir level despite the signs of instability of the landslide.

This theory, after initially being accepted by the investigating judge, was then rejected on appeal as false and lacking in logical basis.

Quite simply, the law governing the nationalisation of electricity companies did not provide for compensation to ‘expropriated’ companies based on the number and value of the plants acquired, but calculated the compensation based on the average stock market value of the company itself during the three years prior to the announcement of the nationalisation.

The testing of the plant would therefore have had no impact on the amount of money that SADE’s owners would have received from the Italian state.

Purpose of the bypass tunnel:

The design of the bypass tunnel by Carlo Semenza was not, as claimed by his detractors, a measure simply aimed at safeguarding the practical functionality of the plant (and, by implication, disregarding the safety of neighbouring villages), but was also a necessary intervention, in the event of the valley being blocked by rock debris, in order to allow the water in the isolated part of the lake behind the landslide to drain away, thus preventing an uncontrolled rise in the lake level that could have threatened the village of Erto or even the village of Cimolais, located beyond the S. Osvaldo pass.

As proof of this, immediately after the disaster, in order to prevent the lake from rising, it was necessary to drain the water through temporary pumping stations and, in the meantime, to dig into the rock to extend the length of the bypass tunnel beyond the dam, as the landslide had blocked the outlet close to the dam. In this way, the natural, so to speak, flow of water was restored.

Tina Merlin, a ‘Cassandra’ of Vajont?

When discussing the Vajont affair, it is common practice to describe Tina Merlin as a ‘Cassandra’, referring to the Greek mythological figure of Cassandra, a prophetess who predicted catastrophic future events, but whose prophecies were not believed by those around her.

This clearly refers to the investigative articles she wrote in L’Unità in the years leading up to the great landslide of 1963.

First of all, we must take into account the fact that Tina Merlin, as a journalist, merely reported in her articles the testimonies and concerns of the citizens of Erto and Casso, and that therefore, if we want to give credence to this description, it should actually be the beliefs of the inhabitants of the valley that are ‘prophetic’.

But looking at these predictions, are we so sure that they corresponded to what actually happened?

The widespread belief in the valley, or at least what transpires from Merlin’s articles prior to 1963, was, in short, that with the creation of the artificial lake, the water would erode the banks, causing the village of Erto to collapse into the lake.

This belief was fuelled by the fact that the village was built on top of an old accumulation of limestone debris, but the ground in question was deemed safe during geological surveys prior to the construction of the dam, and in any case was too high to be affected by the presence of water. Erto was located on the opposite bank to where the great landslide occurred!

The only common point between Merlin’s ‘prophecies’ and what would later become reality is therefore the death of a large number of people following a landslide, which, however, occurred through completely different dynamics that had nothing to do with what was narrated. In fact, there is no mention of the ‘great landslide’ of Mount Toc.

The situation is different, however, if we take into account Tina Merlin’s articles published prior to the disaster, as they were reported in her book Sulla pelle viva (“On Living Skin”). The author reworked her writings to make them more consistent with the actual events, adding details that were originally absent.

In his book, E. Semenza gives an emblematic example of this in relation to an article by the journalist dated May 5th 1959.

The article recounts a meeting of the ‘Consorzio per la rinascita della valle Ertana’ (Consortium for the Rebirth of the Ertana Valley), the consortium created by the citizens of the valley to assert their rights following the expropriation of their land by SADE. The article quotes verbatim:

‘They recall what happened in Forzo di Zoldo a few months earlier (referring to the Pontesei landslide) and express their concern about what could happen in Erto when water is released into the reservoir and its movement, going up and down, erodes the banks, destabilising the old landslide that forms Mount Toc and the one where Erto is built.’

However, neither Forno di Zoldo nor Mount Toc were mentioned in the original article of May 5th 1959.

In conclusion, we can say that Merlin herself actively contributed to the conferral of the ‘title’ of ‘Cassandra of Vajont’, making the transcription of her articles more ‘prophetic’ in hindsight.

Reasons for the failure to build the footbridge in the valley:

Before the hydroelectric plant was built, there were small bridges in the Vajont valley that locals used to cross the gorge without having to go down and then back up again. But these bridges were at such heights that, after the dam was built, they would be submerged by the lake. SADE therefore promised the local population that it would build a new bridge at a higher altitude to restore the passage from one side to the other, but with the approval of the project modification that allowed for the further raising of the dam, and therefore the capacity of the lake, this bridge would also have been at an altitude that would have been occupied by water in the future. It would therefore have been necessary to redesign the promised bridge at even higher altitudes, but this was not ultimately done because the type of terrain that would have affected the anchors of this structure was deemed unsuitable for the purpose.

In the ‘official’ version of the story, this fact is recounted as if it were an indirect admission by SADE of the general instability of the lake’s banks.

As E. Semenza points out in his book, given the V-shape of the gorge, raising the height at which the bridge would have been built would also have meant increasing its length. In fact, a hypothetical bridge connecting the two sides of the valley above an altitude of 722 metres above sea level (the maximum water level of the lake) would have been no less than 350 m long, which would have resulted in a significant engineering challenge, especially given the actual instability of the terrain involved, which was found in preliminary geological studies. However, this instability was only a problem in the context of bridge construction and was not indicative of a general inadequacy of the land that would form the shores of the lake and the dam foundation area, which had very uneven geological characteristics.

It was finally decided to build a road that would run along the lake, a solution that was certainly more inconvenient for the inhabitants of the valley, but simpler and cheaper to build. It should also be remembered that the project also included the use of the dam’s crest, once construction was complete, as a pedestrian walkway across the lake.

Was the change to the project due to greed and ambition?

The decision to modify the project during construction, which would have involved raising the dam and thus increasing the capacity of the reservoir, was attributed by Merlin to Carlo Semenza’s ambition and SADE’s desire to obtain greater profits from the plant.

This could, in all honesty, represent a partial truth, given that C. Semenza was understandably gratified professionally by such a daring project, which would also have been the last major project of his career before retirement, and given that SADE, as a private company, acted with the aim of making a profit. However, in the context of the book she wrote, this statement takes on the tone of malicious speculation - one of many.

Merlin seemed to want to omit the fact that this project was first and foremost a public utility project from which the entire community would benefit in one way or another, and that the increase in electricity production was a demand from all political parties in the country to promote economic growth and employment. It should be remembered that the plant alone supplied a significant percentage of Italy’s entire energy needs.

An overdue paradigm shift

In a sense, we can consider the contribution of by Edoardo Semenza as his “epitaph”, his last attempt to ensure that truth prevailed over mystification before his death on 31 May 2002. Today, we can sadly see that his hopes have not been fulfilled, at least for now. His book represents, for all intents and purposes, an ignored point of view on the matter, but this could change in the future if someone decides to take on the arduous task of bringing his version to the attention of the general public.

It is worth discussing - and I would like to point out that this does not represent what E. Semenza argues in his book, but rather the personal considerations of the author of this article - the ‘synergy’ between SADE and the Italian state control bodies that in those years had to supervise the work taking place in the valley, i.e. the controlled-controller relationship between these two entities.

The ‘official’ theory (promoted by Merlin) highlights a sort of - to use a strong term - servility on the part of public officials towards SADE, with reference mainly to the various authorisations that were granted almost automatically to the Venetian company.

Although difficult to prove, this theory is likely to be compatible with the reality of the facts, not because of the existence of documents or testimonies confirming it, but much more simply because of the economic and social model in which almost the entire world has been living for several decades or centuries now, namely the capitalist model.

In a context where real power is no longer in the hands of state entities, it would be naive to believe that a company such as SADE, a multinational corporation, had no way of exercising any kind of control or pressure on Italian state officials, given the undeniable strategic interest that their work represented for the nation.

E. Semenza himself, who in his book does not miss an opportunity to dismantle every slightest inaccuracy he finds, remains vague when dealing with this specific topic, avoiding going into detail, which, given the vehemence with which he corrects every other misrepresentation he finds, may have tacitly suggested an indirect acknowledgement of the thesis as correct or at least plausible.

It should be recognised, however, that as long as the plant remained under the private management of SADE, the problems that arose were handled in what was then, based on the knowledge available at the time, objectively the best possible way.

Despite Merlin’s accusations, the situation deteriorated after nationalisation, which took place formally in March 1963 (seven months before the disaster), creating a transitional and confusing situation due to the “change of ownership”, where Alberico Biadene - who took over from Carlo Semenza after his death - found himself with no one above him to consult on the decisions to be taken.

In conclusion while it is customary to point to SADE and its managers as responsible for the Vajont catastrophe, the reality is that the main culprit - leaving aside the objectivevy “bad luck” of the circumstances, where everything that could go wrong did go wrong - was the vacuum of responsibility that was created as a consequence of the transfer of the plant to the Italian state.