Veneto will return to the polls in November 2025 to elect its new regional president. This is a provisional date, however, as nothing is certain about this election cycle - not even the date of the elections themselves. In fact, not even the year.

These elections are likely to have repercussions far beyond the region's borders, affecting the political balance in Italy’s government. Consequently, they will also affect the balance of power in Europe.

The following article attempts to shed light on the complex political situation, providing a brief background description of the major players and stakes.

Some Disclaimers

We will never get tired of repeating it: Veneto is not Venetia; therefore, Veneto only partially includes the peoples of Venetia.

Veneto it is an administrative subdivision of the Italian state that currently governs part of the Venetian territories. It was created in 1970, along with the other regions that currently make up the Italian Republic.

When we use the term 'Venetians', we are not referring to the inhabitants of the Veneto region or the city of Venice, but rather to the inhabitants of Venetia - the historical region encompassing a larger area populated by peoples united by common traditions and destinies. The ancient Regio X “Venetia et Histria”, the medieval March of Verona and, later, the Venetian Republic (aka the Serenìsima), were the entities that most successfully brought these peoples together to protect their interests.

The italian state, on the other hand, has always sought to eradicate the Venetians' sense of belonging to their ethnos, and continues to do so to this day. Therefore, we cannot recognise it as being able to perform the same historical mission as its predecessors.

Nevertheless, we must work with the situation we are in, so we believe it is right that Venetians also participate in regional politics - while striving in other domains of local public life - with the collective aim to govern the regions where they live, including Veneto.

The Veneto Region

As an administrative division of Italy, Veneto encompasses the central area of Venetia and, with its 4,800,000 inhabitants, comprises approximately 50% of the total population of Venetia.

Veneto is the region of Venice, Verona, Padua, Palladio's villas, the Dolomites (partially), Prosecco and much more.

It ranks first in Italy in terms of tourist visitors and income (and if we add these numbers to those of the other regions of Venetia, the rest of Italy is left far behind), second in terms of GDP after Lombardy, although it is almost tied with its nemesis Emilia-Romagna.

Not to mention the manufacturing industry: although little affected by the economic boom driven by the Marshall Plan after World War II, Veneto's industry exploded in the 1970s and 1980s thanks to private initiative, often in the form of family businesses. Founded by people who worked “in workshops by day and in the fields by night”, these companies generated a wealth and prosperity that still characterises the region today, and they continue to drive its economy. While some have become famous multinationals - Luxottica being one example - most remain small and medium-sized enterprises, forming part of the supply chain of large companies spread across the continent and beyond, such as the German automotive industry.

In short, we are talking about one of the richest regions not only in Italy, but in the whole of Europe. Much of what has made European civilisation great in the world was born within its borders, both yesterday and today. One example among many? The first internal combustion engine, made by Enrico Bernardi from Verona, who built it a year before the more famous Karl Benz. Also, the Tiramisù.

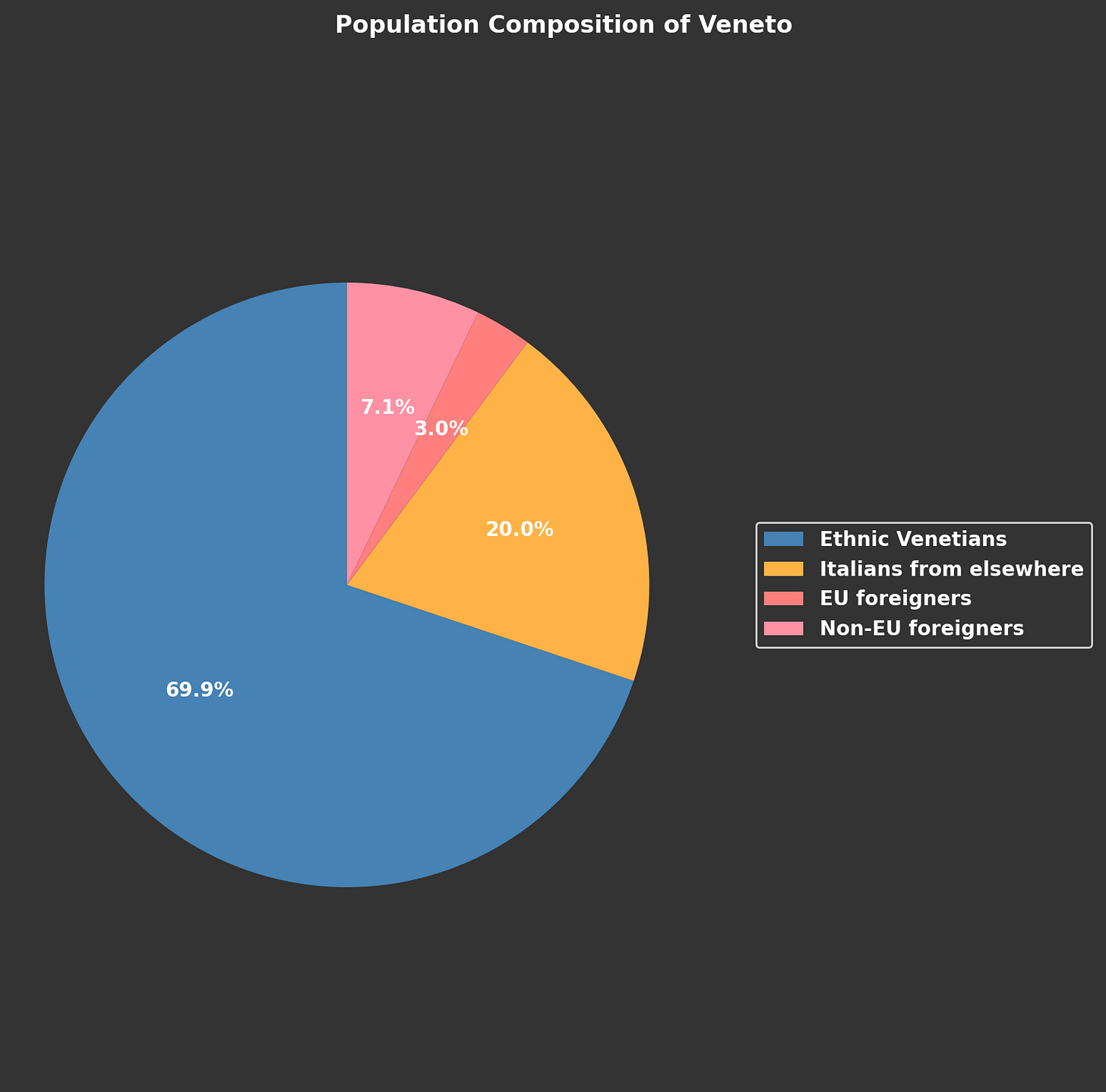

Foreigners make up 10,2% of the population. Of these, 29.8 % are from EU countries, primarily Romania and Poland. The remaining 70,2% come from non-EU countries, primarily Albania, Morocco and Ukraine, although there has been an increase in Chinese and Indian nationals in recent years.

They are scattered throughout the region, which effectively prevents the formation of ghettos or closed communities, as is often the case in large European cities.

Conversely, some smaller towns have undergone significant demographics transformation in recent decades due to the influx of these small yet numerous immigrant groups. If we add to this an estimated 20% of the italian population residing in the region, but originating from elsewhere in Italy, ethnic Venetians make up around 70% of the total population.

Like the rest of Italy, Veneto has suffered from the emigration of many of its native inhabitants in recent years, as well as a declining birth rate. This is leading to the tragic depopulation of the countryside and mountain areas, and threatens the thousand-year-old Venetian urban landscape characterised by many small and medium-sized towns rather than large cities that concentrate people and resources.

Currently, the only thing holding back this trend are the industrial districts, some of which have existed since the days of the Serenìsima. These are clusters of companies located in the countryside and foothills where the renowned Venetian manufacturing industry thrives.

Political Tradition…

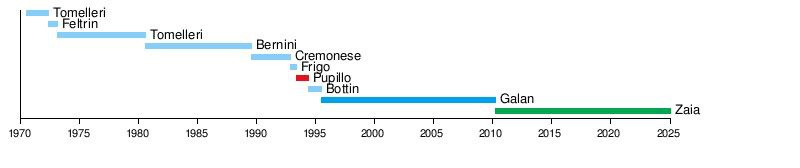

Veneto has historically been one of the strongholds of italian conservatism: since its establishment, the regional governor has always been a member of conservative parties, from the Christian Democrats to the Northern League (Lega Nord, more recently Lega).

The only exception was in 1992, when the Socialist Party managed to briefly elect one of its members to lead the region.

The average Venetian voter is therefore conservative on social issues but liberal on economic issues, and this translates into intolerance of state interference even on welfare, sometimes to the point of rejecting it on ethical grounds, as happened with the introduction of the universal basic income (in 2019, then abolished in 2024): the social pressure on those who wanted to benefit from it, branding them as parasites, was such that it created a strong disincentive to apply for it. Despite this, it is one of the regions with the lowest tax evasion rates in Europe.

…and its Historical Roots

In pre-Roman Venetia, we know that there was a confederation of city-states organised into three classes according to the Indo-European tripartite system. Power was therefore widespread, with public affairs being managed by the heads of extended families (tribes) and discussed outdoors in public places. There are no historical sources that mention kings or tyrants ruling over Venetia, unless we turn to mythology. Joining the Roman Republic with full citizenship preserved this way of life, which slowly became Romanised over the following centuries.

The orderly migration of the population to the lagoon in late antiquity preserved the municipal Roman institutional culture, likely shaping the Venetians' political vision in the Middle Ages. The Venetian Republic, which lasted for almost 1,100 years, had a pragmatic, aristocratic, trade-oriented ruling class. This left a legacy of a strong propensity for self-government, entrepreneurship, and the protection of property rights.

The traumatic Napoleonic invasion and Habsburg rule may have consolidated the conservative ethos, resulting in a mistrust of revolutionary projects. When Veneto (which at the time included the present-day regions of Veneto and Friuli) was annexed to Italy in 1866, this legacy would adapt to the colonial extractive treatment by the Italian central government through a doubling-down of its strong liberal constitutional imprint, rejecting both radical and socialist tendencies.

The rise of small family businesses in the post-war period fuelled the link between the liberal-Catholic tradition and economic development, consolidating the conservative vote in defence of small business 'capital'.

The Political Puzzle behind these Elections

The italian government is currently supported by an alliance of three conservative parties: Brothers of Italy (FDI, led by Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni), the League (Lega, led by Matteo Salvini), and Forza Italia (founded by Silvio Berlusconi).

This same coalition, bolstered by a few regional civic lists, holds an overwhelming majority in Veneto. According to polls, the coalition would also be the clear favourite against any opponent in the 2025 Veneto regional elections. However, an internal disagreement between the majority parties risks redrawing the balance of power in Rome, as each party wants to impose its own candidate to lead the coalition in the region.

Outgoing governor Luca Zaia is one of the most charismatic and cross-party figures in Italian politics. Having been governor since 2010, he has built up personal support that extends far beyond the confines of his party, the League, and even beyond the centre-right. His popularity is nurtured daily on social media by a powerful social media management team.

He began his third term in 2020, having won an impressive 76% of the vote in the regional elections. His term will end in 2025. Current rules prevent him from standing again, but his political influence remains strong. His supporters are calling for the law to be changed to remove term limits, allowing him to stand again. While many consider him to be Salvini's rival within the League, the prospect of his appointment as the new party secretary has receded following general Roberto Vannacci's entry into politics. The general is a figure who is rapidly monopolising italian politics, and we will examine him in more detail in a future article.

Thus, an electoral victory that was once taken for granted now risks becoming a political catastrophe, creating fractures within the governing majority and potentially leading to a stalemate in the choice of presidential candidate. Buoyed by overtaking the League in the last European elections, Brothers of Italy is claiming the right to choose the presidential candidate. Giorgia Meloni's party won a relative majority of votes in Veneto during National and European elections, and intends to capitalize on that result.

Historically, Veneto has been the League's political stronghold. Losing control of the region would confirm the party's decline, as it is already falling in national polls and has been delegitimised by its failure to implement the law most eagerly awaited by Venetians: regional autonomy. Therefore, it cannot be ruled out that the League could threaten the stability of the national government if its choice of presidential candidate is not accepted. This is not just a matter of prestige, but of political survival.

If he is not consulted on the choice of his successor or finds that he cannot stand again, a sensational scenario cannot be ruled out: Zaia could break the mould by taking to the field with his own civic list or establishing a new political entity that is perhaps federated but independent from the League.

Such a move would radically change the rules of the game. Zaia could attract votes from across the political spectrum, challenge the Meloni–Salvini alliance directly, and reshape the centre-right political landscape. It would call into question Salvini's national leadership too. Not only could this determine the future regional government, it could also usher in a new era of leadership for the italian centre-right. It could even set a new direction for the entire national political system.

Curiously, outside the broader conservative camp, the traditional political forces (progressives and ecologists) are not exploiting the vacuum left by the stalemate over candidate selection among the favourites. Instead, it is those currently outside the regional council - liberals and separatists - who are taking advantage of the situation.

The Issue of Autonomy

One of the main themes of the election campaign will be achieving greater regional autonomy through the transfer of powers from central government to the region.

This law is opposed by both Fratelli d'Italia, who needs a strong central government to consolidate their power, and by the majority of people in central and southern Italy. Consequently, autonomy is a considerable embarrassment for the governing coalition and is therefore not being discussed. Interestingly, the League has not yet issued an ultimatum on this law in Rome, but it will be impossible not to talk about it in Veneto.

The call for autonomy in Veneto and Lombardy is not new. The (then Northern) League was founded as a party with the aim of separating the regions of the Po Valley from Italy, a goal that was later transformed into a federal reform, which was never achieved.

After its nationalist transformation under Salvini, the League supported a consultative referendum on autonomy in Veneto and Lombardy, in 2017, which demonstrated overwhelming support for increased regional powers: 98% in Veneto and 95% in Lombardy voted “yes.” to get more autonomy rights. These two regions produce 31% of Italy’s tax revenue but receive only 22% of public spending.

The 2023 autonomy bill cleared the Senate, but remains stalled in committee on its practical application, which seems more and more distant as the months go by.

Public frustration is mounting. A 2025 SWG poll found that 71% of Venetians support devolving more competences from central state to the region, compared with just 27% of Sicilians. The Veneto Chamber of Commerce estimates that delays in autonomy cost €1.4 billion annually in lost EU co-financing. The regional council has hinted at invoking Article 259 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, arguing that Italy’s unilateral horizontal transfer system violates the subsidiarity principle.

The Game has only just begun

With less than six months to go until the vote, the situation is still uncertain. But one thing is certain: Veneto will be at the heart of Italian politics in autumn 2025.

This is a pivotal moment for the region, which must decide whether to preserve its manufacturing and agricultural traditions or to attract foreign capital and become the new European high-tech hub.

Sources

ISTAT – Statistica Today: Turismo 2023, novembre 2024 (pdf). (Istat)

ISTAT – Conti economici territoriali – Anni 2021-2023, comunicato stampa, gennaio 2025. (Istat, Istat)

Regione del Veneto – Rapporto statistico interattivo: La congiuntura, 2025. (Statistica Regione Veneto)

Wikipedia – voce “Enrico Bernardi” (accesso 2025). (Wikipedia)

Regione del Veneto – “Veneto: Stranieri residenti – anticipazioni dati 2024”, gennaio 2024. (Integrazione Migranti)

ISTAT – Censimento permanente della popolazione in Veneto – Anno 2023 (pdf), aprile 2025. (Istat)

ISTAT – Indicatori demografici – Anno 2024 (pdf), marzo 2025. (Istat)

Reuters – “Italy’s demographic crisis worsens as births hit record low”, 31 marzo 2025. (Reuters)

Wikipedia – voce “List of presidents of Veneto” (accesso 2025). (Wikipedia)

Consiglio Regionale del Veneto – Risultati del referendum consultivo per l’autonomia 2017 (pdf). (doc989.consiglioveneto.it)

Very informative piece. As a Venetian living in Australia, your content fulfils me with pride and placates my often overwhelming nostalgia.