Among the many historical discoveries being squawked on the web by archaeo-mystery sites is one that should not be categorised as a hoax, but should instead be investigated.

We refer to the alleged existence of the remains of Alexander the Great in Venice. As is well known, the basilica of St. Mark, the metropolitan cathedral, houses the remains of St. Mark the Evangelist under the high altar. The basilica itself was built to house his remains.

The evangelist Mark was, in fact, chosen by Doze Justinian Partecipazio to consolidate the supremacy of the lagoon city: the saint had evangelised the Venetians, becoming their patron and symbol (the winged lion). Transferring the veneration of the saint to Venice, which thus became the destination of his cult, would have brought prestige to the city and enormous advantages, including economic ones. The relics were thus stolen on commission by the doze in 828, in Alexandria, Egypt. The protagonists were two merchants-spies: Buono da Malamocco and Rustico da Torcello.

The Construction of St. Mark’s Basilica

Partecipazio, who died a year after the stolen relics arrived in Venice, ordered in his will the construction of a basilica "worthy to permanently house the saint's bones".

The first church was thus built in 832 next to the ducal palace; the building was then replaced in situ by a new one in 978. The present basilica, on the other hand, dates back to a later reconstruction completed in 1094: in that year a body - supposedly of St Mark - was found within a pillar, likely hidden during the many works and then forgotten. Other restorations and reconstructions followed one another, without changing the location of the church.

The Two-Body Problem

In short, a somewhat troubled history, with repeated and undocumented movements of the patron's remains, which, however, have always remained there.

In 1811, it was decided to inspect the burial site and move St Mark under the high altar to avoid the risk of flooding. Thus came the first surprise: the inspector, Count Manin, found himself with two corpses, one intact, including the head, of the other only a few bones. At that time, there was no DNA evidence or Carbon-14 analysis, and investigations were superficial. It therefore ended there, without too much fuss. But why two bodies?

The History of Alexander the Great's Tomb

It is necessary, then, to take a step backwards, to Alexandria. As is known, Alexander the Great, who died in the year 323 BC, was buried in the city that would become the capital of Ptolemaic Egypt. According to the version reported in the sources, Alexander was embalmed and transported to Egypt at the behest of Ptolemy I, his former general. Preserved by the Ptolemaic dynasty, the ruler's body, after an initial burial in Memphis, was transferred to Alexandria and placed in a gigantic mausoleum measuring 800 by 600 metres, similar to the sacred precincts of Memphis.

According to most scholars, the mausoleum was located near the intersection of the two main roads that ran orthogonally through ancient Alexandria and was known as the Sema (tomb) or Soma (body) of Alexander.

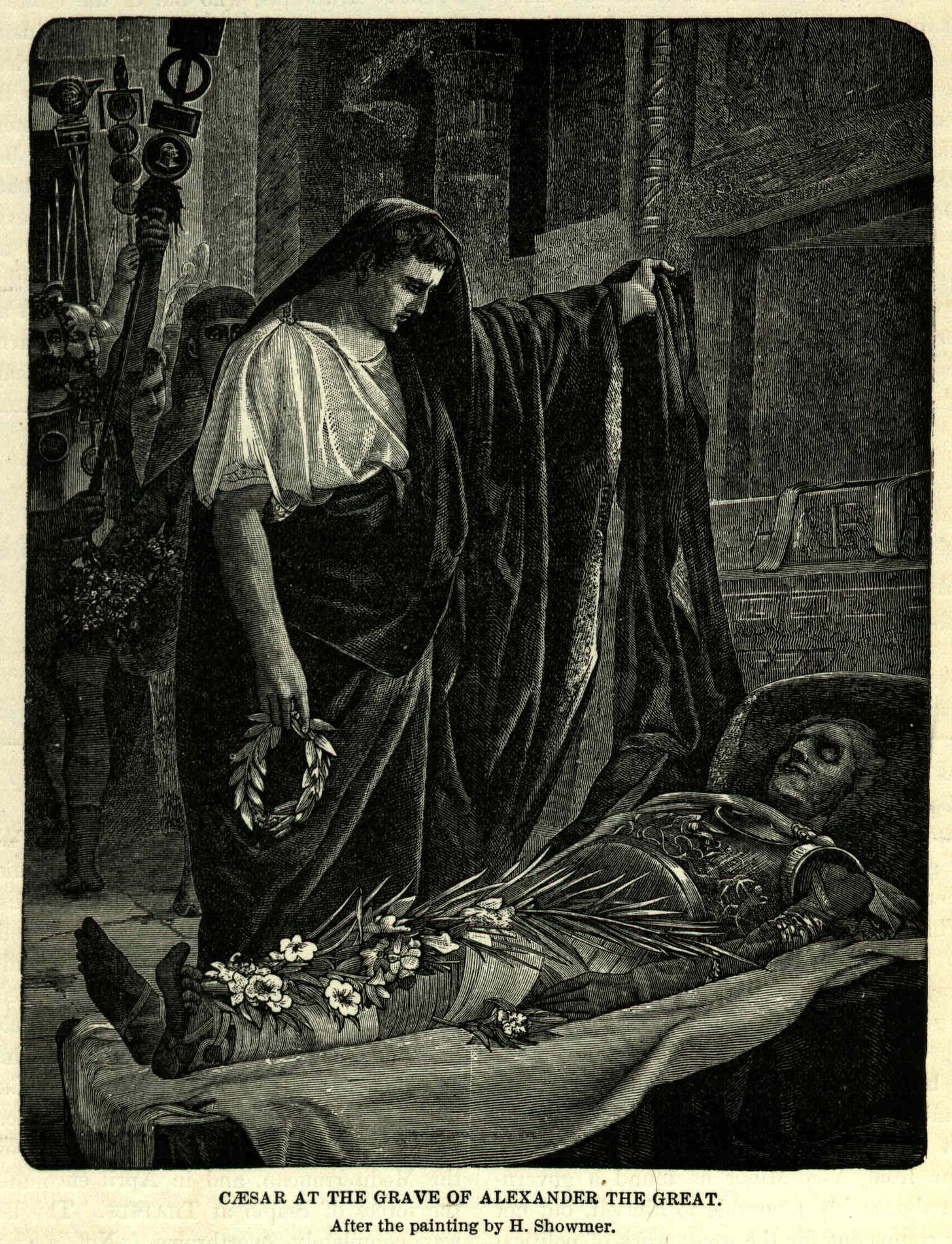

He was venerated for centuries and paid homage to by illustrious figures at least until the year 390 AD: from Caesar to Augustus, to Caligula (who, according to Suetonius, took possession of his armour), from Septimius Severus (who had the tomb sealed so that the hero's sleep would no longer be disturbed) to Caracalla.

"Octavian," writes Suetonius, "placed a golden wreath and scattered flowers on the sarcophagus that held the body of Alexander the Great in the sanctum sanctorum; they then asked him if he wanted to see the tomb of the Ptolemies. He replied: My wish is to see a king, not corpses'. 'The Soma, as it is called, is a part of the royal quarter. This was the city wall, which contained the burial places of kings and that of Alexander': so Strabo, an eyewitness in the year 25 before the Vulgar Era.

Diodorus, for his part, claims to have visited Alexandria and seen with his own eyes the tomb of Alexander the Great consisting of a temenos, a sacred enclosure that was part of a mausoleum. Octavian Augustus honours Alexander the Great, the Soma. And so we come to 391, the year of Emperor Theodosius' edict banning the pagan religion from the empire. We can suppose that the gradual physical destruction of the mausoleum started then, and q few decades later Alexandria was also devastated by a tidal wave. Thus, the memory of the Soma was lost.

Let’s backtrack to the 1st century AD, when St Mark - who was also the city's first bishop - preached. Tradition reports that the saint was martyred there, dragged by horses until his head was severed and, as a sign of further contempt, condemned to be cremated; it is said that some of the faithful managed to steal his burnt remains to give him a proper burial. In the 4th century, after the defeat of paganism, news began to spread of pilgrimages to the site of the Evangelist's martyrdom.

It was the Christian custom to replace pagan cults with their own, and so the pagan cult of Alexander was replaced with the Christian veneration of St Mark, creating, in effect, a relic of the saint. The veneration took place in a small church built just inside the walls, at the eastern gate of medieval Alexandria (called the Cairo Gate or Rosetta Gate), exactly where ancient maps indicated the Mausoleum, i.e. at the crossroads of ancient Alexandria: in fact, the walls are believed to be the remains of those of the enclosure of Alexander's tomb. In short, in the same place the body of St Mark appeared and Alexander's (officially) disappeared.

The Recovery of the Relic

Over the years, the little church also became a place of pilgrimage for Venetian merchants who gave thanks there for the success of their journeys. When Buono da Malamocco and Rustico da Torcello arrived in Alexandria to steal St. Mark, they were facilitated by the circumstance that the church was the object of predatory aims by the Islamic governor. So it was that the guardian priests, in order to protect the relics, allowed the two Venetians to take away the saint's remains (or, perhaps, they were bribed). When they removed the tombstone, however, they realised that there were two bodies. Having no time to investigate, the merchants placed all the remains in a large basket, covering it with pigs' heads to conceal the spicy perfumes from one of the two mummies (and evade inspection by the Islamic port authorities). After a month and a half of sailing, the two disembarked in great secrecy in Venice, and only when it was done, with the relics placed in a small chapel, did the doge inform the population.

Chugg’s Hypothesis and the Quest for the Tomb

This whole story, which reads like a Salgarian adventure novel, has been corroborated with truth thanks to the studies of a British researcher, Andrew Michael Chugg, published in his two books 'The Lost Tomb of Alexander the Great' (2004) and 'The Quest for the Tomb of Alexander the Great' (2007). 'Already in 2006 at the conference Heroes, Heroisms, Heroisations, organised at the University of Padua,' writes Venetian researcher Teresa dalle Vacche (Il Gazzettino, 29.6.2012), 'Chugg expounded to the academic world the evidence of the connections, according to him, existing between the history of the relic of St. Mark and the mummy of Alexander the Great', he continues.

In support of his thesis, Chugg refers to an important clue that would establish a direct connection between St. Mark and Alexander the Great: a large and heavy block of stone found in 1963 during some maintenance work in the foundation of the apse of the Basilica of St. Mark, in an area very close to the crypt where the saint's body was originally placed and pertaining to the first building built by Doge Justinian Partecipazio.

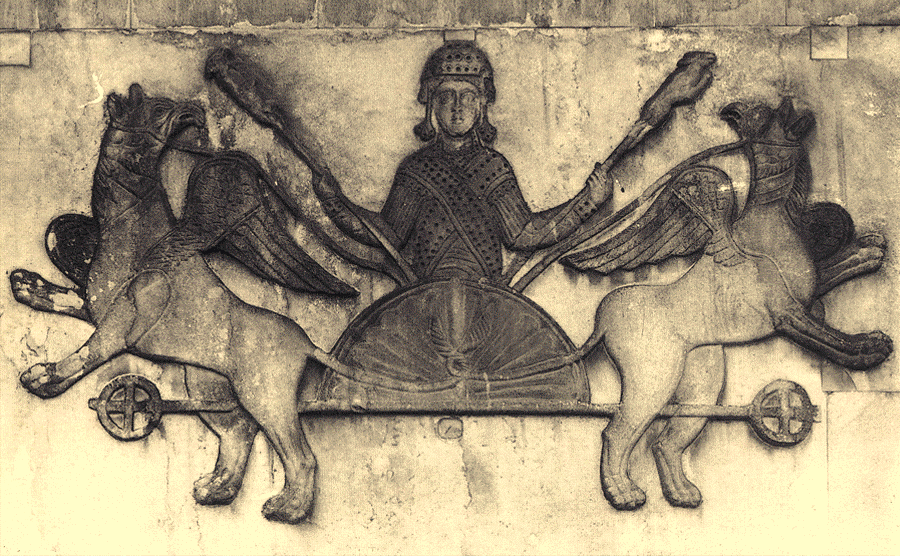

The stone, now preserved in the Cloister of Santa Apollonia - the current seat of the Diocesan Museum of Sacred Art in Venice - features some reliefs: on the main facade, a shield with the eight-pointed Argeade star, symbol of the royal family of Philip II (Alexander's father), two schinieri and the trace of a long lance, perhaps a sarissa; on the left side a sword hanging from a band, identified as the Macedonian sword.

For Chugg, the stone would be a stone fragment from a Macedonian royal tomb, possibly from Alexander's Soma/Sema. It should now be pointed out that initial analyses carried out on the composition of the material would seem to disprove the English scholar's thesis by giving the stone a local origin (stone from Aurisina, near Trieste).

However, in a locality that Chugg identified close to the western arm of the Nile Delta, fragments of temples made of stone from Aurisina have been found. Thus, if the stone from which the altar of St. Mark's Basilica is made comes from Egypt, and that fragment is therefore a remnant of Alexander's original tomb, then the most logical hypothesis would be that the Venetian merchants Buono and Rustico stole Alexander's body instead of St Mark's. Or perhaps, both, explaining the double burial unearthed in Venice.

Sources

A. M. Chugg, The Lost Tomb of Alexander the Great

A. M. Chugg, The Quest for the Tomb of Alexander the Great

E. Cardarelli, Alessandro Magno a Venezia?

M. Casolari, Chi è sepolto in S. Marco a Venezia? E’ ora di analizzare quei resti

Hahaha, benon. Ła storia ła podi da èsar senpre stranìa.