Lega (Nord?)

Subversion and Decline of a formerly regionalist party

For much of the 1990s and 2000s, Lega Nord (Northern League) stood as the most visible political expression of Northern “Italian” discontent. Born from a coalition of regional autonomist leagues and anchored in the productive regions of Lombardy and Veneto, the party rallied against Rome’s centralized governance, high taxation, and neglect of Northern economic and cultural aspirations.

Today, the party - rebranded simply as "Lega" and stripped of much of its original Cisalpine identity - finds itself in decline, eclipsed nationally by Fratelli d’Italia and increasingly estranged from its original northern strongholds.

The root of this decline lies not merely in electoral cycles and such eventualities, but in a deeper abandonment of its founding ethos - rooted in the Cisalpine ethnocultural milieu - in order to expand its voter base in Southern Italy, which ultimately led to a crisis of identity. In the near future, Lega’s ambivalent nature may be resolved - one way or the other.

Origins and Formation in the Late 1980s

Lega Nord was founded in 1989 amid a wave of Northern Italian regionalist movements, uniting several autonomist groups - such as Lega Lombarda and Łiga Veneta - under the leadership of Umberto Bossi.

Its emergence reflected deep-rooted regional grievances in Italy’s productive North, where many felt overtaxed by Rome, culturally distinct from a South perceived as parasitic, and constrained in their ethnic aspirations by the administrative and cultural centralism and corruption that plagued the italian state since its inception.

It articulated a message of federalism, cultural preservation and - in some instances - even outright secession under the banner of "Padania", a proposed Cisalpine nation-state.

The party’s rise coincided with a tumultuous period in italian politics: the late 1980s and early 1990s saw changing economic conditions and the collapse of the post-war party system due to corruption scandals (Tangentopoli), creating a new demand for political representation that the nascent Lega was poised to fill.

Bossi’s role was pivotal: he supercharged the regionalist scene by channeling it into the broader currents of change sweeping Northern Italy in the 1980s.

Early Lega Nord’s platform: pro-market federalism, “Padania” and pro-European integration

From the outset, Lega Nord’s ideology centered on regional autonomy and an anti-centralist, anti-elite message. The party championed a form of federalism or even secession - famously invoking the notion of “Padania” (an imagined independent North based on ethnocultural affinity and shared historical experience) - as the solution to what it saw as Rome’s mismanagement and corruption.

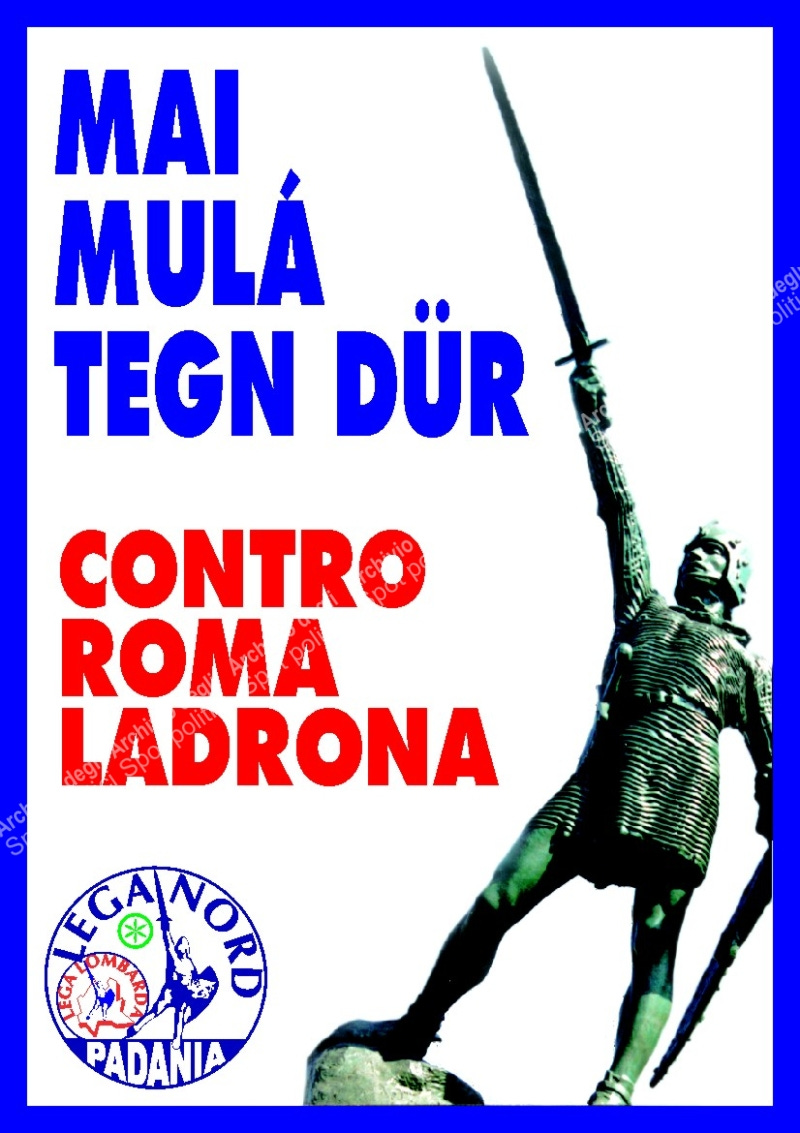

Its rhetoric cast “Roma Ladrona” (“Rome the big thief”) as an extractive oppressor of Northern taxpayers, portraying Southerners and the italian state bureaucracy as freeloaders holding back the industrious North through the extraction and redistribution of tribute without a corresponding supply of services.

In a way, Lega Nord was a precursor to contemporary European identitarian movements in the way it recognized the role of both the internal migration from Southern Italy and the external immigration from outside of Europe into the Cisalpine region as a process with negative consequences in the economic, demographic and social spheres - the same ones that plague Europe today on a greater scale.

Economically, the party was pro-market and aligned with the interests of small-business owners and self-employed Northerners. However, its appeal was not merely class-specific: Bossi’s goal was not to create a liberal “entrepreneur-party”, or a socialist workers’ party, but to represent the ensemble of productive classes, workers and entrepreneurs alike. The political representatives of the Northern League came from different backgrounds, ranging from the Communist Party to libertarians. However, the intellectual soul of the party came from the classical liberal tradition pervasive in the Cisalpine region, that never managed to express itself in italian politics after the Second World War.

The party’s economic vision embraced a “family–small business–community” ethos that expressed itself in policies supporting low taxes, local enterprise, and fiscal federalism - letting each region keep and spend more of its own revenue, which endeared Lega Nord to many Northern entrepreneurs and industrialists. At the same time, the party’s appeals extended to blue-collar northerners disenchanted with the Left, though Bossi’s movement never became explicitly “left-wing”.

Lega Nord was - at least in the beginning - regionalist first and foremost, seeking to provide a political voice to legitimate northern grievances that were suppressed by Italy’s corrupt centralism - itself dominated by southern ethnic interests.

From Protest to Power: Lega Nord in the 1990s and 2000s

In the early 1990s, Lega Nord rapidly evolved from a protest movement to a major political force, riding the collapse of Italy’s old parties. It scored its first significant wins in 1992, and by 1994 the Lega had enough support (over 8% nationally) to enter a governing coalition with Silvio Berlusconi’s center-right.

This was a turning point, marking Lega’s first taste of national power, but also its first major strategic dilemma. Bossi’s party joined Berlusconi’s government only to walk out after a few months, bringing that government down in late 1994. The dramatic break reflected Lega’s ambivalence - torn between being an “anti-system” insurgent and a partner in government. After 1994, Bossi flirted with positioning the Lega as a third pole in italian politics, neither left nor right, even exploring a possible rapprochement with the Left at one point.

During 1995-1996, Lega Nord went it alone, escalating its separatist rhetoric: in 1996 the party even proclaimed the “independence of Padania” in a theatrical ceremony in Venice. Though largely symbolic, this secessionist phase underscored Lega’s core demand for radical federal reform, which resonated with a sizable portion of the northern electorate.

By the late 1990s and early 2000s, however, Lega Nord began a period of consolidation and partial moderation as it returned to Berlusconi’s center-right fold. The years 2001-2011 saw Lega serve as a junior coalition partner in three Berlusconi-led governments, gaining experience and policy influence.

In those years, the party achieved a degree of institutional stability and territorial consolidation in its northern strongholds - where local mayors and administrators would retain the ideals of the old Lega Nord - something that would later lead to internal clashes after Lega’s transformation under Salvini.

In high politics, Lega leaders secured high-profile posts (Umberto Bossi as Reform Minister, Roberto Maroni as Interior Minister, etc.) and pushed key parts of their agenda - for example, a constitutional reform for regional devolution (approved by Parliament in 2005, though later rejected by a national referendum) and stringent immigration and security laws.

Ultimately, Lega was reliant on national coalitions: its allies were parties with a strong electoral base in Southern Italy, whose elites - being disproportionately over-represented in politics, education, military, bureaucracy and the Judiciary - have always been strongly opposed to any federal reform of the Italian Republic that would devolve any rights to self-governance to its regions. Because of this, Lega was unable to fundamentally restructure the Italian state.

With hindsight, we can identify another “flaw” in Lega Nord’s strategy to reform the italian state from within: to only pursue the fiscal and economic domain among the many Northern grievances with the italian state, leaving the ethnocultural and linguistic spheres in the background.

By the end of the 2000s, Lega Nord had completed its transformation into a party that was, de facto, part of Italy’s right-wing establishment - albeit one still based on a northern platform. This meant shifting further to the right on the political spectrum, especially on issues of immigration, national identity, and law and order.

Internally, the late 2000s also brought strains: Bossi’s health problems and a series of scandals tarnished the party’s image. By 2012, revelations of embezzlement and nepotism in Bossi’s inner circle rocked the party (though it was never clear if it really was the leadership’s fault or if other hidden factors were at play). The once-fiery outsider party now appeared sclerotic and mired in the same corruption it condemned. Bossi was forced to resign in 2012 amid these scandals, and the stage was set for a new leadership and - with it - a reinvention.

Matteo Salvini’s Deal with the Devil (2013 - Present)

The Lega’s seeming salvation - and dramatic transformation - would come with Matteo Salvini, who attained party leadership in late 2013. He would take over a weakened movement polling under 4% and, within a few years, turn it into a resurgent force on the national stage - at a cost.

The party formally remained “Lega Nord”, but Salvini aggressively rebranded it simply as “Lega” (The League) - signaling a break with its exclusively northern identity and concerns. This change became official in 2018 when the word “Nord” was dropped from the party’s electoral logo, reflecting Salvini’s ambition to build a pan-Italian right-wing populist party. Under Salvini’s tenure, Lega underwent a profound ideological transformation: the formerly cross-party regionalist platform gave way to full-throated nationalism and nativism - Salvini wrapped himself in the italian flag and adopted the slogan “Prima gli italiani” (“Italians First”), pivoting the party to attract Southern electors.

According to some early activists with whom we have interacted, the party is still legally divided into the Lega and the Lega Nord for internal administrative reasons. Therefore, it is possible to join either the Lega or the Lega Nord - Łiga Veneta in the case of Veneto, which results in different obligations. We do not know why this choice was made.

Lega’s regionalism was thus been replaced by an empty form of nativist nationalism - Lega no longer emphasized North–South differences or federalism, focusing instead on themes like immigration and the defense of Italy from “external threats”. In Lega’s new narrative, EU bureaucrats in Brussels took the place of Rome as the new oppressors of the “italian nation”.

Salvini’s Lega moved to the far-right on the ideological spectrum (at least in its rhetoric), aligning itself with other European populist-right movements. He forged ties with France’s Marine Le Pen and promoted a vision of “sovereignist” politics opposed to both the EU’s supranational authority and to globalization. This was yet another U-turn by Salvini’s new strategy for Lega: while Bossi initially supported the idea of a “Europe of Regions” as a way to break the yoke of the italian “nation-state”, Salvini’s routinely blamed Brussels and EU budget rules for Italy’s economic troubles.

Issues like immigration became the party’s foremost rallying cry - a shift already underway, but accentuated by the post-2014 migrant crisis. Between 2014 and 2017, over half a million migrants (many fleeing wars in Syria or Libya) arrived in Italy by sea, overwhelming the reception system, and Salvini tapped into public anxieties over this influx. Casting himself as Italy’s protector, Salvini promised to “send back immigrants” and even floated exit from the euro currency as solutions. In short, he reframed the League’s mission as defending all italians from external dangers - whether migrants, Brussels, or global finance.

We should note that the shift from Rome to Brussels as the “enemy” of Lega was not just a change in geographic scale: this imperfect equivalence hides a deeper shift in Lega's platform and voter base.

Formerly, Lega Nord’s grievances with Rome were based on actual economic metrics, and on an ethnically-based need for self-determination, attracting votes from across the political spectrum and not necessarily opposed to European integration - seen as a way to break Rome’s yoke on Padania.

On the other hand, Salvini’s populist narrative broadened the geographic reach of its voter base, but appealed mostly to a growing eurosceptic section of the public, which often blamed the EU out of prejudice rather than from any rational argument. We don’t think it’s a coincidence that Salvini’s Lega often flirted with pro-russian talking points, perhaps as a way to demonstrate opposition to the EU.

We also don’t think it’s a coincidence that this shift in priorities was accompanied by Lega’s need to appeal to Southern italian voters, whose third-worldist historical perspective - an inferiority complex directed against anything they perceive as “nordic”, both Northern European and Northern Italian - clearly mirrors the irrational populist arguments against European integration.

Lega’s Apogee and Decline (2018-2022)

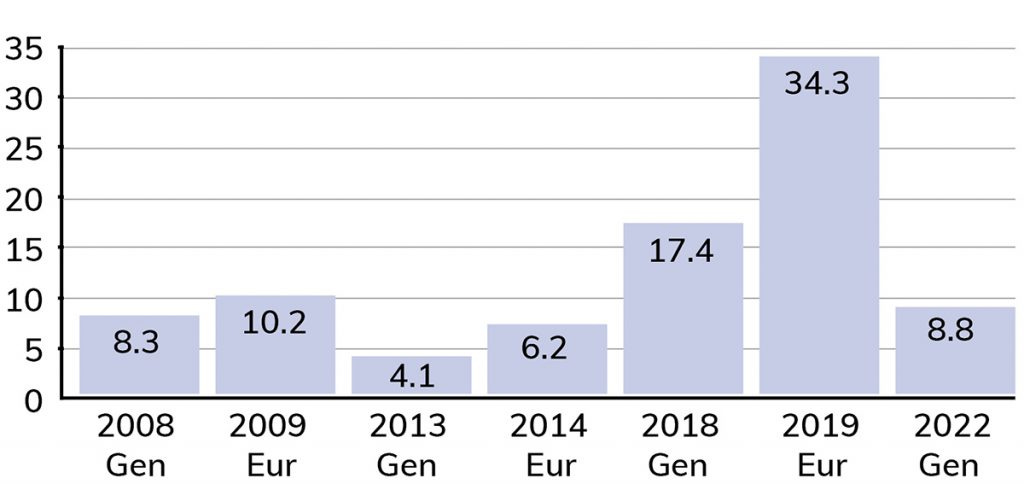

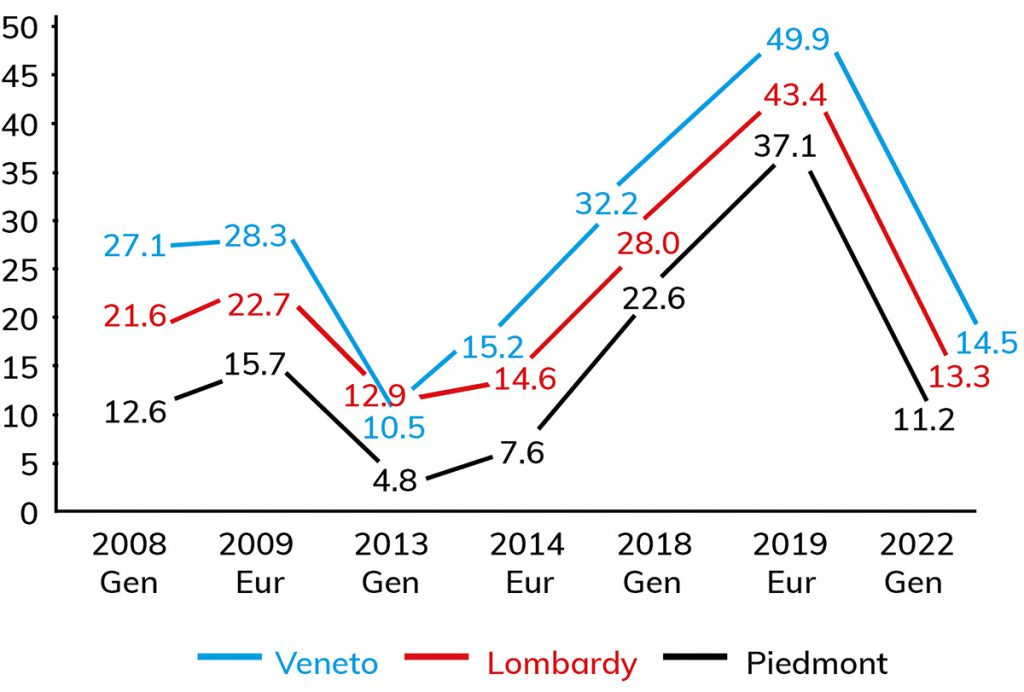

These changes paid off - at least initially - in a spectacular fashion. In the 2018 general election, the party won 17.4% of the vote (up from just 4% in 2013), surpassing Berlusconi’s Forza Italia to become the largest party on the right.

Salvini then stunned observers by entering government not with his traditional right-wing allies, but in a populist alliance with the southern-based left-wing populist Five Star Movement (M5S). In June 2018 Salvini became Deputy Prime Minister and Interior Minister in the M5S–Lega coalition, the so-called “government of change”. During his 14 months in that role, he pursued hardline anti-immigration policies - closing Italy’s ports to NGO rescue ships, pushing harsh security decrees, and giving voice to nationalist sentiments on a daily basis.

In the May 2019 European Parliament elections, Lega topped all parties with 34.3% of the vote - its best result ever. Notably, Lega made unprecedented inroads in Italy’s central and southern regions. By 2019 Salvini’s party captured roughly one-quarter of the vote in the South, a historic result considering that just a few years back the South was portrayed as “the Enemy”. Salvini managed to transpose the old North-versus-Rome struggle onto a new axis of Italy-versus-Brussels, uniting voters around nationalism and anti-immigration sentiments. However, the very rapidity of Salvini’s ascent and of Lega’s transformation carried the seeds of a downturn.

In August 2019, emboldened by strong polling, Salvini gambled and pulled the plug on the governing coalition, demanding new elections (hoping to become Prime Minister). The move backfired: instead of elections, the M5S struck a surprise deal with the center-left, ousting Lega from power. Over the next years, the Lega’s support ebbed as Italy’s political focus shifted. During the COVID pandemic, Salvini found himself in opposition (for part of 2020) and then awkwardly joining a pro-EU technocratic unity government under Mario Draghi in 2021.

This was a remarkable U-turn: Salvini, who had once barnstormed Italy on a “No Euro” tour in 2014 to denounce the single currency, ended up backing Draghi - the former European Central Bank chief - as Prime Minister. Such reversal blunted Lega’s anti-establishment reputation and, by the time of the 2022 general election, support for the party had collapsed from its 2019 highs. The party managed only about 8.8% of the vote - perilously close to its 2013 result.

Lega would be decisively overtaken by its right-wing rival, Giorgia Meloni’s “Fratelli d’Italia” (FdI). Essentially, many Central and Southern Italian voters who had flocked to Salvini’s hard-right message shifted to Meloni’s party, which offered a more consistent national-conservative program and had never (yet) strayed from its core principles or switched sides in government.

In its Northern heartlands, Lega lost ground as well: in 2022 it polled even lower in Lombardy and Veneto than it had in 2008, likely due to the effective abandonment of its original northern platform. This alienated voters in the North, leaving them with no choice but to vote for Meloni as the “lesser evil” candidate. Still, Lega manages to retain a higher proportion of the vote in its original heartlands, likely due to voters’ inertia and a dense and effective grassroots network of web of mayors, coincilors and seasoned activists - precisely what Fratelli d'Italia is lacking in the North.

As of today, Lega remains in government as part of Meloni’s right-wing coalition, but now as a junior partner with diminished clout. Salvini’s gamble to remake Lega into Italy’s dominant force succeeded only temporarily. The “nationalist turn” brought great success in 2018-19, but failing to sustain it, Salvini arguably compromised the credibility of the Lega and opened the door for an even more ideologically coherent right-wing competitor (FdI) to eclipse it, losing credibility even in its northern strongholds.

Lega’s slow death

Throughout its evolution, Lega’s strategy and language have shifted dramatically from decade to decade, leading to a persistent ideological ambiguity - perhaps as a deliberate strategy to appeal to a wider voter base at first, but with the unintended consequence of a potentially irreparable loss of trust.

Today, the party’s identity crisis is evident. In 2022, veteran Northern League figures (including founder Umberto Bossi) have pushed back, creating a “Comitato Nord” faction within the party to reassert the old regionalist priorities. They argue that Salvini’s nationalist pivot “abjured the League’s core values” and that the party must “return to its roots” to regain support in the North.

One such attempts manifested in 2024, when Paolo Grimoldi - Lega Nord’s Secretary in 2015-2021 and supporter of its original values - broke off from Salvini’s Lega and founded “Patto per il Nord”, as a specifically northern party inspired by Bossi’s original vision.

Salvini, meanwhile, resists fully reverting to the past and seems intent on keeping up the charade: advocating for “regional autonomy” arrangements as a way to retain the support of its northern base, while still playing on the national stage. However, this balancing act is difficult, since full-throated regional autonomy claims can conflict with the party’s role in a national government coalition that demands unity of purpose.

The tension between the Lega’s original mission (regional self-government and federalism) and its reinvented mission (national populism and anti-EU sovereignism) remains unresolved, and the more this ambiguity persists, the more its voter base (both original and newer) will erode.

What Future for Lega?

As we write these lines, August is drawing to a close and impatience is growing in Veneto, where an election date has yet to be set. This is particularly true of local businessmen, who have historically supported the regional Lega establishment.

The conservative coalition's internal impasse over the choice of a new candidate for governor in Veneto hinges on the outcome of the elections in another region, Marche. While this game of political chess is being played out in Rome between three right-wing parties (Lega, Fratelli d'Italia and Forza Italia), the Venetian political class is suffering helplessly despite its economic weight.

'We have reached total irrelevance. We had more influence during the First Republic,” the former head of Confindustria Veneto [Enrico Carraro, ndr] and president of the eponymous metalworking company tells. ‘We keep waiting for a candidate when we are on the brink. It is humiliating to have to depend on Marche. There is no natural leader here, and it shows.' The vacuum that Zaia will leave is likely to remain. 'We have always got on very well with the governor. An era will soon come to an end, but he has not secured his succession, which is a serious shortcoming for those who administer.'

The results of the Veneto regional elections will decide the future not just of Lega, but of italian politics, and not only in the short-term (potentially breaking the governing coalition) but also on a longer time scale because they take place in a period of transition for all the most relevant political parties in Veneto - the end of the “Zaia era”.

Whatever its electoral performance may be, Lega seems to have already chosen the path of national-populism, doubling-down on it and effectively formalizing its abandonment of its original northern roots. Two recent developments are exemplary of this.

First, is the open support of Salvini’s Lega to the figure of Roberto Vannacci, a Tuscany-born general that in recent years emerged as right-wing populist figure, then as member of the European Parliament, and lastly as Lega’s Deputy Secretary.

Secondly, Lega’s backing of the Strait of Messina Bridge - a long-debated link between Sicily and the mainland repeatedly revived and cancelled - now aligns with the government’s final go-ahead on 6 August 2025, at a publicly funded cost of €13.5bn. Estimates have risen from ~€4–6bn in the mid-2000s to today’s figure; the project has already absorbed over €1 bn in studies, litigation and company costs. For three decades the bridge has functioned less as an infrastructure plan and more as a totem in Italy’s culture-political wars that has already absorbed significant public funds. Engineers and fiscal critics cite seismic/wind challenges and value-for-money doubts, while ANAC/DIA warn of high mafia-infiltration risks. By championing it, Lega signals a clear centralist agenda rather than a northern-focused one.

Seeing how the internal fractures within Lega have led to the splintering-away of key northern figures, and how the void left by the party in those same regions hasn’t yet been filled - meaning that no political party is interested in representing nothern ethnic interests - we will likely see the emergence of new candidates, new ideas, and new parties more able and willing to represent the increasingly disenfranchised Cisalpine peoples in the near future.

Bibliography

https://www.limesonline.com/rivista/morta-e-l-italia-non-la-padania-14624928/

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334709473_The_roots_of_the_Lega_Nord's_populist_regionalism

https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/03/italy-elections-lega-nord/554753/

https://theloop.ecpr.eu/what-happened-to-matteo-salvinis-league/

https://www.ft.com/content/1920a116-fd3b-11e8-ac00-57a2a826423e