With a powerful fleet, numerous bases and a mastery of maritime flows, the Republic of Venice made logistics the main tool for increasing its power and ‘navigate uncertain waters.’ From its small lagoon, it became a thalassocracy ruling over Mediterranean trade for several centuries.

At the end of the first millennium, the city of Venice emerged as a maritime power. It would take advantage of the rise of the Western principalities’ and the Byzantine Empire’s economic revival to emerge as a central emporium of the Christian world. Venetian ships, ports and infrastructure would embody the military and commercial strength of Venice, capable of defending its interests and projecting its power throughout the Mediterranean.

As The Third Venetia, we believe that looking at our past is the only way to address the future effectively. Throughout this article, we will highlight certain historical accounts from the X to the XVII centuries that relate to the power dynamics between the Republic of Venice and other regional actors. This period of history, and generally the part of our past that follows the fall of the Roman Empire, presents certain similarities to what could be defined as today’s ‘Resurrection of History’.

The undoing of Fukuyama’s 1992 proposition, which is centred on the standpoint of liberal democracy, is in fact the beginning of another process: US-led globalisation is in crisis and the peripheries of its empire are in turmoil - from Donbass to the Caucasus, from the Middle East to Taiwan - along this new ‘Mackinderian geographical pivot of history’. Unsurprisingly, the Trump administration is anticipating the fall of globalisation to capitalise on this enormous change of power dynamics.

At a time when human organisations are unable to cope with complexity and interconnection (i.e. globalisation), when positions on the chessboard are constantly shifting and rearranging, predicting the behaviour of other actors becomes virtually impossible and one has to manage a ‘certain degree of uncertainty’. Thus, suddenly, everyone feels vulnerable and conflicts arise.

It is crucial to understand that the more this scenario becomes challenging for organisations, the greater the opportunities they can exploit. But you not only have to be in the right place at the right time, you also need to have the right strategy in mind. As we have previously seen, the Republic of Venice exemplifies this ability to seize opportunities despite its comparatively modest resources.

The following is a series of elements providing relevant insights for today’s strategists.

The Venetian Fleet: Achieving Technical Superiority

By 961, the Venetian fleet had already played a central role in aiding the Byzantine reconquest of Crete. By transporting soldiers, Venetian ships became an essential logistical component of the military operations of the Eastern Roman Empire.

At the same time, the organization of port infrastructures in Venice and later in its colonies reinforced this logistical power in the Mediterranean. Well-equipped ports allowed for the rapid loading and unloading of galleys, facilitating trade and optimising logistical flows. These infrastructures were essential for maintaining a high freight rate and a commercial pace capable of meeting market demands.

Because of this key role, Venice was able to obtain (and then exploit) certain trade privileges to strengthen its commercial position. From the X century onwards, the Venetians negotiated their aid to the Byzantine Empire in exchange for said privileges.

In 992, Emperor Basil II granted significant tax reductions to Venice in exchange for military aid from its fleet.

Subsequently, the imperial decree of Alexios I Komnenos in 1082 was a major turning point: it abolished the main commercial tax representing 10% of the value of goods for the Venetians, who were even able to settle in Constantinople and establish their own neighbourhood.

Other successive decrees (1126, 1147, 1148, 1187, 1189, 1198) confirmed and extended these privileges, consolidating Venetian domination of Byzantine trade despite the emergence of competitors such as Genoa and Pisa.

These privileges notably allowed Venice to dominate the trade in precious silks produced in Thebes, cereals from Thessaly, oil and wine from the Peloponnese, and soap and cheeses from Crete. This enabled Venice to become a key component in the logistics of trade within the Byzantine Empire, allowing it to control strategic products and to extend the economic influence of the ‘Serenìsima’ ever further.

It should be noted that Venice also provided troop transport during the Fourth Crusade (1202-1204). The Serenissima took advantage of this to exert pressure and modify the itinerary as, initially, the crusaders stopped to plunder Zara (now Zadar, Croatia), under then-Hungarian domination, which became a Venetian possession.

Finally, the crusaders ended up in Constantinople, where they plundered the city. In the end, the expedition enabled the Venetians to recover the trade routes lost in 1171 (following the expulsion and confiscation of their property by the Byzantine Emperor Manuel I Komnenos), this time to their sole and complete benefit.

Controlling Trade Routes: The importance of Establishing Reliable Strongholds

Venice was able to transform its geographical advantages into a formidable logistical strategy.

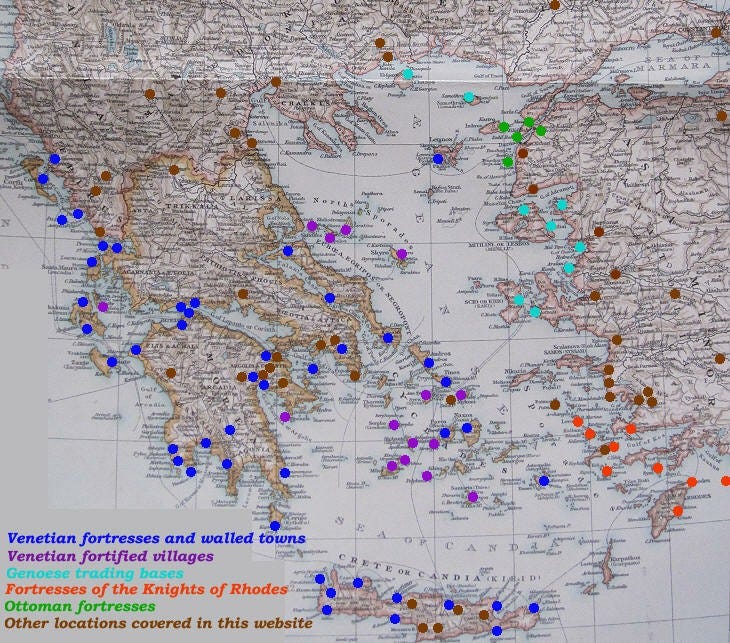

For example, even before the fall of the Eastern Roman Empire, Constantinople was not a final destination but a stopover on a larger trade route. The Serenìsima, embodied by the Stato da Mar, set up a network of maritime possessions and colonies enabling it to control the vital trade routes in the Mediterranean. This strategy of logistical domination was based on a series of key strongholds that guaranteed the security and efficiency of trade.

The Ionian Islands, particularly Corfù, played an important role in the Venetian strategy. The island served as a gate to the Adriatic Sea, protecting the entrance to this Venetian Gulf. At the same time, the Venetian Peloponnese, with its ports of Coron and Modon (now Koroni and Methoni, Greece), was the ‘eyes of the Republic’.

These Venetian possessions served as advanced naval bases for monitoring and controlling maritime movements. Crete, meanwhile, was an essential Mediterranean crossroads. The fortification of Chania, after the expulsion of the Genoese in 1252 and the construction of well-equipped ports, made the island a veritable outpost for securing the sea routes in the eastern Mediterranean. The island also made it possible to guarantee a continuous supply of agricultural products and other local resources.

We can also mention the case of Dalmatia and Venetian Albania. Cities such as Zara, Spalato (Split, Croatia), Ragusa (Dubrovnik, Croatia) and Durazzo (Durrës, Albania), in addition to guaranteeing supremacy in the Adriatic, provided a link with the Balkan kingdoms. By extension, these possessions gave Venice a degree of control over trade between the Adriatic and the Aegean.

In the ‘Romanian Countries’, on the borders of the Venetian thalassocracy, cities such as La Tana/Tanais (Azov, Russia), located at the mouth of the Don, served as a maritime outlet for Chinese luxury products transported along the ‘Mongol route’. In direct competition with Genoa, which had a strong presence in the Black Sea, these trading posts even handled the maritime logistics of intra-regional trade, for example transporting grain from Crimea for resale in Asia Minor.

This strategy, which aimed to increase the number of logistical support points in the Mediterranean (and even in the Black Sea), was also based in part on strategic alliances with influential Greek families. Venice thus created stable commercial networks and integrated local merchants into its economic empire. This ‘commercial semi-colonisation’ made it possible to strengthen control over the controlled territories and ensure fruitful cooperation with local actors. This strategy facilitated the integration of Byzantine administrative and economic structures into the Venetian empire, thus consolidating Venice's economic and military domination.

The Sapient Use of Public-Private Partnerships: Creating Synergy, not Conflict

Venice's success in controlling trade routes and exploiting its maritime power was largely based on an unprecedented form of cooperation between the public and private sectors.

The Venetian state, which was highly bureaucratic, was directly involved in the organisation of the city's maritime trade. The ‘Serenìsima’ established a system of convoys of public galleys, known as mude (‘expeditions’), to secure the transport of valuable goods such as spices and silks. These convoys, made up of two to five merchant galleys, were organised annually or biannually, following predefined routes to strategic ports such as those of ‘Romanie’ (declining Byzantine Empire), the Black Sea, Alexandria and Flanders.

The state ensured the protection of merchant ships by imposing strict navigation rules and requisitioning these galleys in case of military need. At the same time, private shipowners continued their independent commercial activities. Their ships mainly transported raw materials and less valuable goods, thus complementing the functions of the ‘public’ galleys. The distinction between merchant galleys and private fleets was based on technical and economic criteria: the galleys were armed and belonged to the state, while the private ships, larger and unarmed, were freely operated by private owners.

The Venetian patricians, who often owned the ships, participated in the management of the public galleys while maintaining their own private businesses. Private initiatives, supported by partnerships between influential merchant families, ensured the dynamism of trade and the expansion of commercial networks. Thus, the distribution guaranteed effective complementarity: public transport guaranteed the security and regularity of trade, while private transport offered flexibility and responsiveness to commercial opportunities. It can also be noted that the decline of this public/private system corresponds to the beginning of the decline of Venetian power in the XVI century.

Venetian ‘public/private’ cooperation also manifested itself through infrastructure development projects. The administration of the Venetian quarter in Constantinople is a striking example of this. The Venetian authorities, in particular the doges, delegated the management of large portions of territory to Venetian ecclesiastics because it was impossible to manage these properties directly from a distance. The Venetian churches in Constantinople strengthened the expatriates' sense of community and belonging to Venice. In addition to their spiritual role, these religious institutions were responsible for official weights and measures, thus guaranteeing the honesty of commercial transactions. This integrated management of spiritual and commercial aspects reflected the effective cooperation between public and private actors in the Venetian Maritime Empire.

The establishment of the Venetian trading post at La Tana/Tanais in 1429 is yet another example of public-private synergy: the local Venetian soldiers, sent and paid for by Venice, were also artisans. It was they who built and maintained the Venetian trading infrastructures, making the trading post viable, while strengthening the links between Venice and Venetians in the colonies.

Battling for Key Resources: Gaining a Competitive Advantage

Venice demonstrated a remarkable ability to control the trade of strategic raw materials in the Mediterranean. Once again, it was mainly through its logistical capabilities that the ‘Serenìsima’ was able to position itself as a key player in this field.

Towards the end of the XII century, Venice began to strictly control the trade in salt, an essential product for food preservation. It first intensified its imports of sea salt before obliging Venetian merchants to transport salt when they returned to Venice. This helped to reduce transport costs thanks to the use of salt as ballast.

The Magistrato al Sal, a sophisticated administrative apparatus, was then set up to regulate the salt trade with transport duties, tolls and a crackdown on smuggling. In the XV century, Venice even bought the large saltworks of Cervia, enabling it to export salt to the entire Po Valley and as far as Tuscany. This strategy was developed in the Mediterranean in a bid to create a monopoly on the ‘white gold’ of the time.

It is also worth noting that during the wars with Genoa, Venice innovated by creating robust salt warehouses in its Dorsoduro district. The city had more than twenty warehouses in the XVI century, guaranteeing sufficient reserves in times of crisis. This sophisticated logistical infrastructure made it possible to maintain a regular supply and to manage salt resources efficiently, which were crucial for the Venetian economy.

Venice also managed to establish a strategic relationship with the Republic of Ragusa to secure a regular supply of precious metals. Although Venice did not directly control the silver and lead mines in Bosnia and Serbia (among the most important in Europe), Ragusa (Dubrovnik, Croatia) played a crucial role in the trade of precious metals extracted from these regions. Ragusan merchants ensured the extraction, transport and sale of these ores in collaboration with the local sovereigns. Dubrovnik was thus a sorting and distribution centre which ensured transport to Venice, from which the metals would in turn be redistributed in Europe and the Mediterranean.

Even during the Hungarian-Venetian wars, Dubrovnik - allied with Hungary - continued to trade with Venice, demonstrating the vital importance of the city as a hub of European trade.

Concluding Remarks

The Republic of Venice’s mastery of logistics, infrastructure, and diplomacy offers critical lessons in increasing resilience and adaptability for modern strategic thinking, insights that remain relevant today, as globalisation enters a state of crisis and new power dynamics reshape international trade and political alliances.

A key takeaway from Venice’s success is the importance of technical superiority. The Republic’s ability to maintain a state-of-the-art fleet, optimise port infrastructure, and develop an efficient logistical network ensured its competitive advantage over rival states. In today’s context, the principle remains the same: any individual, organisation, or nation must strive for irreplaceability in its field. Mastering advanced technology and developing unique capabilities through R&D are fundamental to always ‘have a sit at the relevant table’.

Venice also teaches the necessity of securing loyal allies and strategic bases. The establishment of strongholds - from the Ionian Islands to the Black Sea - ensured Venice’s ability to project power and secure trade routes. In modern terms, this underscores the need for resilient supply chains, stable bi/multi-lateral geopolitical partnerships, and a strong foundation of trusted collaborators. The lesson is clear: even amidst uncertainty and shifting landscapes, having secure footholds enables sustained influence and operational security.

Furthermore, the Venetian approach to public-private cooperation provides a powerful lesson in economic synergy. By integrating state-sponsored convoys with private merchant ventures, Venice maximised efficiency while ensuring strategic control over trade. This model suggests that contemporary economic policies should avoid rigid dichotomies or zero-sum thinking between public and private interests. Instead, governments and businesses should align their efforts to promote shared prosperity, leveraging complementary strengths to drive sustainable development.

Another crucial insight comes from Venice’s ability to identify and exploit key strategic resources. The Republic’s dominance in salt and precious metals trade demonstrates the necessity of recognising critical commodities and structuring logistical networks to capitalise on them. In the present day, whether in securing energy supplies, rare earth elements, or data infrastructure, controlling essential resources remains a defining factor of geopolitical and geoeconomic strength.

Ultimately, the success of Venice was not simply a matter of wealth or military power but of strategic foresight and adaptability. As the world transitions away from the assumptions of the post-Cold War order, Venice’s history can serve as a guide for navigating the new complexities of global power.

The ‘resurrection of history’ demands a strategic recalibration. The capacity to anticipate change, capitalise on instability, and align interests effectively will define success in the emerging global order.

Fantastic article.

The revitalisation of Venetia is of great importance to us Slavs, as it not only weakens our Italian enemy, but also gives us a reliable partner on the Apennine Peninsula.

How do you view Venetia in relation to "Padania" and other such concepts?